|

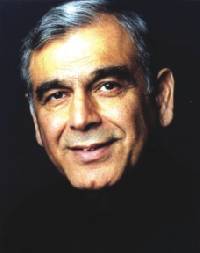

Obituary

The Dream Merchant Dies

Peter Bradshaw

Ismail Merchant, who died at the age of 68 following surgery for abdominal ulcers, was the Indian-born film producer of brilliance, garrulity and charm who created a universally recognisable movie brand, in a remarkable partnership with the American director James Ivory that lasted for more than 40 years and 40 films. Ismail Merchant, who died at the age of 68 following surgery for abdominal ulcers, was the Indian-born film producer of brilliance, garrulity and charm who created a universally recognisable movie brand, in a remarkable partnership with the American director James Ivory that lasted for more than 40 years and 40 films.

His was a startling career; he had directed films himself, and he also pursued a passion for food: he opened a restaurant in 1993, and published several books on travel and cuisine. Although they started with dramas set in Merchant's native India, such as Shakespeare Wallah (1965) and Bombay Talkie (1970), Merchant and Ivory came to be the rajahs of stately period-costume cinema, often based on 19th- and 20th-century literary works from Britain, or the Anglocentric America of Henry James.

The films were full of ladies in elaborate dress twirling parasols, and gents with florid whiskers, all elegantly disposed on the lawns of sumptuous country houses. But under this picture-perfect finery, passions seethed.

American audiences had been brought up on television's Masterpiece Theatre, showing highlights of classy British drama, introduced by Alistair Cooke. Merchant shrewdly sensed that there was an appetite for something similar on the big screen, and in Ivory he found a director of like-minded taste and judgement, although they had a habit of quarrelling about financial and artistic matters.

If this was creative tension, it worked resoundingly well. Together, they brought out a series of confident, well furnished adaptations including James's The Europeans (1979), The Bostonians (1982) and The Golden Bowl (2000), EM Forster's A Room With A View (1985), Maurice (1989), and Howards End (1992); they also adapted Kazuo Ishiguro's The Remains Of The Day (1993), which was set in a country house in the 1930s, with Anthony Hopkins as the repressed butler, struggling with his feelings for Emma Thompson's housekeeper.

The late 80s and early 90s marked the height of Merchant's success. There were Oscar nominations for A Room With A View, Howards End and Remains Of The Day, and the first two of those won Baftas. Merchant-Ivory had created a powerful genre of their own, which surely influenced Martin Scorsese's adaptation of Edith Wharton's The Age Of Innocence in 1993.

But many critics and movie-makers detested what they regarded as Merchant-Ivory's ersatz classiness, their uncritical, touristic approach to fine buildings and fancy manners, and their seeming indifference to the hidden cruelties of class division. Their films were derided as reactionary, pseudo-literary products that fitted in all too easily with the Reagan-Thatcher years. Some people joked that reversing the order of their surnames gave a better idea of their stock in trade.

In the second half of the 90s, the Merchant-Ivory genre fell calamitously out of fashion. Peter Biskind's book, Down And Dirty Pictures, records that Quentin Tarantino, before the first ever showing of his ultra-violent gangster movie Pulp Fiction (1994) bounded on to the stage, asked those in the audience who liked The Remains Of The Day to raise their hands, and then pointed to the exit, yelling at them: "Get the fuck out of here!"

Merchant had been born Noormohamed Abdul Rehman, son of a middle-class Muslim family in Bom bay, but spent most of his life in the West, having been sent to the US by his family so that he should become a businessman. He took a master's degree in business administration at New York University.

Merchant's early films were set in India; the first was The Householder (1963), photographed by Subrata Mitra, who was cameraman for the great director Satyajit Ray. Shakespeare Wallah (1965) showed a troupe of English actors strolling through India, and starred the Kendal family: Geoffrey, Jennifer and a girlishly young Felicity. Its hint of the formalities of the height of the Raj, the British rule over India, perhaps directed Merchant backwards to the original style that had been Edwardian and Victorian Britain.

The next two Indian movies, The Guru (1969) and Bombay Talkie (1970) were unsuccessful, and the Merchant-Ivory team returned to the US, where they found an uncertain reception for Savages (1972), their experimental allegory about civilisation, and The Wild Party (1974), a movie about the notorious Fatty Arbuckle rape case during Hollywood's silent film era.

At the end of the 70s, Merchant began the most successful period with his version of James's The Europeans, and then Heat And Dust (1983), adapted by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala from her own Booker Prize-winning novel. A string of well-upholstered, bookish hits followed, which made Merchant's fortune and reputation.

Merchant and Ivory were still in production: The White Countess, a period drama set in China, is yet to be released, and they were working on The Goddess, a musical about the Indian deity Shakti, unexpectedly starring Tina Turner.

In 2003, Merchant was made an honorary fellow of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts; he received the Commandeur de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France, and in 2002 he received the Padma Bhusan from the Indian government, which is the equivalent of a knighthood.

He did not marry.

Ismail Merchant (Noormohamed Abdul Rehman), film producer, born December 5 1936; died May 25 2005

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |