|

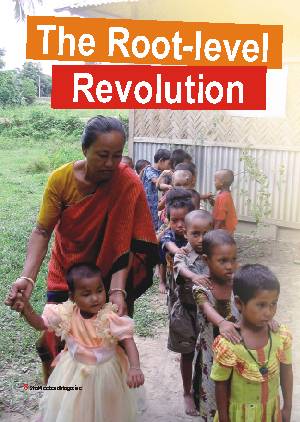

Cover

Story

In a small thatched house, a few kilometres away from Rangamati proper, Shefali Chakma is teaching numbers to her regular group of children between three and six years. She follows an UNICEF curriculum specially designed for the small children of the hilly districts. As she says out loud a number while pointing her finger to pictures of different fruits, the number of which corresponds to the number uttered, the children listen eagerly. Learning numbers with the aid of pictures certainly prickles the young minds; they clearly cannot hide their enthusiasm and mirth. Children here learn the basics in their own language as well as in Bangla, and that too in an atmosphere where education easily diffuses with fun and games. In a small thatched house, a few kilometres away from Rangamati proper, Shefali Chakma is teaching numbers to her regular group of children between three and six years. She follows an UNICEF curriculum specially designed for the small children of the hilly districts. As she says out loud a number while pointing her finger to pictures of different fruits, the number of which corresponds to the number uttered, the children listen eagerly. Learning numbers with the aid of pictures certainly prickles the young minds; they clearly cannot hide their enthusiasm and mirth. Children here learn the basics in their own language as well as in Bangla, and that too in an atmosphere where education easily diffuses with fun and games.

The eighteen children who sit around their teachers are of Chakma origin. Here at the heart of their own village, inside the small hut, they learn numbers, recite rhymes, play games that are designed to check on their personal hygiene and strengthen their insight for a couple of hours every weekday. Their teacher's role extends beyond the periphery of the thatched cottage. She oversees the state of hygiene of the children, supports government health workers in providing immunisation and other health services to the community, gives advice to the pregnant mother and gives out vitamin A to the post-natal mother. This multi-tasked change agent is called the para worker. The learning centre that Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Board's booklet refers to as 'the focal point of the community', truly is the nucleus of all the development and awareness-building activities. It is called the para centre.

|

A para worker's responsibility is varied, one of them is to ready the young minds for future education. |

The para centre that Shefali heads is at Moushmara para or village, it is in the mouza (an area consisting of several villages) of Katachhuri, Rangamati. On the same cloudless day of the monsoon, when the heat of the sun still seems pleasant, in front of the para centre, Rubi Chakma, the government health assistant, administers TT vaccine to the women who gather round her. "A para centre is the epicentre of all activities. All twenty-five households in this village are under the jurisdiction of this para centre, I don't have to go searching for them door to door, I let the para worker know on which day I'll be visiting and the villagers get the news through the para worker," says Rubi whose job makes it imperative to visit the area eight times a month.

As Rubi carries on giving another villager a TT shot (with a new syringe), Md Shamsuddin the health inspector of the Health Department of the government, supervises her work. This para centre has been operating for the last five years. Before that, these health officials would have to go to the para centres of a nearby village, where villagers of Moushpara would travel for vaccination or other health services.

|

| Putting hygiene first, children learn the basics under the supervision of the para worker |

Maya Chakma is a farmer and a mother of Aruna Chakma, a four-year-old girl, who attends the para centre. Maya cannot speak Bangla, she says, "Aagey schoolot naubaar, aagey Khhaajor-beejor thaathek." A bilingual villager named Shukrabaj Chakma translates, "when there was no school, they used to remain dirty." This is how most of the villagers perceive the presence of the para centre. They connect it with hygiene, education and awareness on health issues. Which is exactly what the ICDP project intends to do.

ICDP stands for Integrated Community Development Project: it is the result of a joint effort by the Chittagong Hill Tract Development Board (CHTDP) and the UNICEF.

CHTDP was formed way back in 1976, with the aim of socio-economic development of the people living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts region. On July 11, 1980 the government and the UNICEF signed a 'memorandum of understanding'. The programme focused on reducing child and maternal mortality, eliminating malnutrition, reducing of water borne diseases (the rate of which is high in the region), expansion of basic and primary education through formal and informal teaching methods, creation of self-employment through micro-credit programmes.

|

| Games are an integral part of the daily activities at the para centres. |

The ICDP programme first covered three mouzas of the region on an experimental basis, later it was extended to 11 mouzas of the three hilly districts in the 1982 to 1985 phase. Now after 1985 to 1995 phase the number of mouzas have increased to 75. These mouzas are scattered around the three hilly dirstricts, namely Rangamati, Khhagrachhari and Bandarban.

"There are 2220 para centres in 375 mouzas," according to Jan-E-Alam, deputy project director, UNICEF assisted project, Rangamati. Fortunately the government eventually extended its support and at present is paying for the programmes centred on the para centres and the para worker. "At the beginning of the new phase that started in 2000, GOB (Government of Bangladesh) did not get involved. In 2002 govenrment support amounted to 45 percent of the total expenditure, in 2003 it saw an increase of another 25 percent, and from 2003 government is providing the entire cost of running the programme," Says Alam.

|

| Today's child psychology confirms that the pre-school activities are vital to the cognitive growth of each child |

UNICEF had envisaged the role of the para workers and the activities that centre on the para centres, and the government has now taken charge of the financial aspect of it. "As for the reading materials, visual aids and toys and teaching paraphernalia, UNICEF is providing them free of cost," Alam relates.

MD Qausar Hossain, Project co-ordinator of Khhagrachhari UNICEF branch, stresses the fact that para centres are not mere pre-schools for little children, "They are like information centres. You will get the names of the children who received BCG, TT, Polio, DPT, Measles, and Hepatitis B virus vaccines. There is this government programme that ensures each child will receive four vaccines in four different stages against six prevalent diseases, you go to a para centre and you will find out when and how many times a child has received the vaccines, and who are still left to be vaccinated," Hossain points out. In each para centre there are charts that depict the condition of the pregnant women, when they gave birth, how old the newborns are, and what health condition of the pre-natal women and their children are in. The para worker keeps track of all this and more. "She is a community leader. In the last Union Parishad election 50 para workers won their seats, they left their work but it only shows that the para centres are not only nurturing small children but also women as the leaders of the community," says Alam.

|

Most school-going children fondly remembers their days at the para centre |

Alam is undisturbed by the fact that the dropout rate of para worker is a high - one in ten. "These dropouts too are contributing to the community, they have been empowered through training, they posses the information on awareness building and now as the responsible persons of their community they too are contributing to the development process," Alam continues.

Hossain says that it was difficult at the beginning to induct a para worker. "Now there are four to five candidates competing for a single post. We prefer that the para worker be a woman and also has a schooling of at least up to class eight," he adds.

|

| Children at the Moushmara centre, playing with toys during one of the game sessions |

Although everyone in the community is proud of the duties that a para worker is performing and is sympathetic towards her, her multi-dimensional task earns her only five hundred takas a month. In most of the para, the villagers were demanding that the remuneration of the para workers be raised to an 'acceptable' level. As for the para workers they try and earn their keep by doing something else. Each worker has already received training in METL (Multiple ways of teaching and learning), ECD (early childhood development), WATSAN (Water and environmental sanitation), ARI case management, as well as post-natal vitamin A supplementation.

In addition to the usual training, Shefali Chakma, the para worker of Moushmara para centre, has also been trained in making handicrafts, but she has little time to pursue this skill to earn extra income. She sews clothes of the villagers to make ends meet.

|

A para worker's role is multi-dimensional, she counsels the mothers regarding their health and hygiene |

Para centres are like an organic part of each neighbourhood. "Para centres are established only when the villagers feel the need to have one in their vicinity; none were thrust upon them," Alam assures. The villagers built the centres with their traditional method using bamboo. Villagers of each para not only built their para centre by their own hands, but they also paid for its building materials. A villager too donates the plot for the centre. As far as the centre of Moushmara is concerned, Shefali is the one who took the first initiative. "I applied for the para centre. I faced an interview at the development board. After my appointment was confirmed as the para worker I received training for 26 days," she relates. After her training, a committee of five was formed where the village head or the karbari, as he is known locally, became the chairman with the land giver, the para worker and other two villagers as its members. All the para centres are managed by this five-member-committee.

Even the tube-well that is under the project of DFID is partially funded by UNICEF. In keeping with the wishes of the villagers, it was set up near the para centre so that villagers have access to water. Shushavan Khisha, the deputy project coordinator, ICDP and CHDB says that the practice of hygiene is related to knowledge. The para centre plays a vital role in spreading this information. Every month there are three Uthan Baithaks or meetings that the para worker presides over. The community learns hygiene practices from the para worker. Such awareness leads to a qualitative change in life. In Moushmara each member of the community paid Tk 20 to raise a total of two thousand as contributory amount towards setting up of the water point.

|

Mothers in each village acknowledge the role of the para centre linking it to hygiene, health and other community services |

Para centres are also centres for running the integrated programmes. Hossain cites the example of the multilingual books that they developed, "Shishu Academy, government's education department and the ICDP project officials designed the book for pre-school children. Funded by UNICEF, this book is multilingual. It was piloted in 2002," he continues.

Hossain is emphatic that each para centre is playing a pivotal role in linking the government services with that of the others. "Linkages of programmes of different organisations is one thing for which the para centres are responsible," Hossain argues.

At Ganja para, Khhagrachhari, there is a mixed crowd of children of Bangali, Tripura, Marma, and Chakma origin. Ajit Prova, the para worker is older than most of her counterparts that are mostly made up of young women. "The centre was established in 2003, but even before that the villagers built a centre of education where I used to teach. After it turned into a para centre I not only teach children but also counsel pregnant and prenatal mothers as well as give all health and hygiene tips," says Prova.

As for the mothers of Ganja para, like any other villagers, they hope that children who are attending para centres will do well once they are allowed admission in primary schools. "It has been proved that the children who received training in the para centres do well at school, they are more receptive and even show more ease at learning and at mingling with others," stresses Hossain.

Although the officers involved with the project agrees that not all the centres are operating in the manner of the Ganja para centre or any ideal para centre for that matter, the villagers are united in their demand for development of the para centres. At Gouranga Baishnob para, Rangaur, most of the parents of the attending children gathered in front of the centre to stress the need for the repair of the structure. Although the officers involved with the project agrees that not all the centres are operating in the manner of the Ganja para centre or any ideal para centre for that matter, the villagers are united in their demand for development of the para centres. At Gouranga Baishnob para, Rangaur, most of the parents of the attending children gathered in front of the centre to stress the need for the repair of the structure.

|

| The para centres have raised hope for the health of both the children and the mothers |

Whether the edifice is weathered or newly built, the centres have become an integral part of the communities across the hilly district. At high noon, at Master para, in Ramgar, where the para worker Domra Ching Marma presides over a uthan boithak to give health tips to the pregnant mothers, the young and the old pay heed. Domra Ching takes the help of the relevant book where there are visuals to aid her. She is giving instructions to the mothers to feed the newborn shal-milk, which is often wasted as tradition instructs the mother against early breast-feeding.

Regarding the para centres the UNO of Ramgar has put his view in a nutshell, he said that it is an enviable project, the result of which can only be seen after five years. He has high hopes regarding the future contribution of the project in the total development of the hilly districts. As for the indigenous people of this region their dreams for a better life are aptly expressed in the words of a Chakma mother, she said, "Aaja Nau Thaubohi," (Why should not we have hopes.)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |