|

Cover

Story

When Going When Going

Gets Tough

Shamim Ahsan

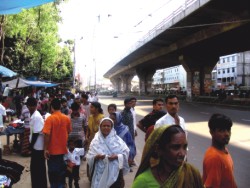

Dhaka, one of the most ill-planned cities in the world, has seen a consistent rise in terms of population over the last one and a half decades, but the most basic infrastructural requirements needed to accommodate that ever-soaring population have never been undertaken. While it is possible to mention any number of resultant problems, commuting certainly ranks among the greatest woes.

|

Luxury buses may ensure a more comfortable ride, but getting on one is quite a challenge |

Dhaka is a terrible city for every variety of commuters. Whether one travels by rickshaw, or bus, or auto-rickshaw or cab or even on foot, a journey within Dhaka city is a virtual nightmare.

Commuting in Dhaka is inevitably tied to getting locked in terrible traffic jam that puts one's patience to test. Commuting in Dhaka is often physically challenging, especially for those who travel by local bus. Travelling by local bus is like fighting a battle where one never wins and always ends up exhausted. Commuting in Dhaka is also hazardous -- drivers of a large number of motor vehicles drive recklessly and carry fake license. Commuting in Dhaka is taxing, in more ways than one. Not only is precious time wasted just waiting in hellish traffic; the waiting also eats at our spirit and sense of well being; after making a single journey one often ends up with a sagging spirit.

It's almost impossible to quantify either in terms of time or money the Dhakaites have to lose due to traffic jam, but a glimpse into any individual commuter's plight gives an idea about the collective misery of the public.

|

| With too many commuters chasing too few buses, the streets are unnecessarily chaotic. |

For a large number of commuters in Dhaka, bus (local buses, most of which are mini in size) is the only option, simply because it is affordable. But the cheap fare comes at a terrible price. A bus ride within Dhaka city is a formidable journey. From getting on a bus to disembarkation, it is a virtual war; in between, it is a continuous hassle while sweating incessantly amidst continuous shoving and pushing from all around, gasping for breath. "I could still bear up with this if the bus did not have to halt every few minutes in a jam, especially in this hot and humid weather," says Shajal Dhar, a salesman at a gold shop at Chadni Chawk. It takes him 1.15 to 1.30 hours to move from Doyaganj, where he lives, to Nilkhet, his workplace. There are at least four to five spots where traffic jams are regulars and when luck is not on one's side one may have to put up with a couple of additional irregular jams as well.

Traffic jams aside, these local buses ply whimsically, further multiplying the travel time. "They stop anywhere they like and at every bus stop they halt for an indefinite time even though the bus is full to the brim and will not start unless passengers start shouting at them," alleges Shahabuddin, a fruit vendor near the Gulisthan underpass.

Traffic Sergeants entrusted with the task to ensure smooth traffic movement, are often accused of compounding the commuters' woes. They may stop a bus right in the middle of the street and start scrutinising the license and necessary papers taking all the time in the world, causing more time loss and more suffering for the passengers who are crammed inside the bus. "They willingly keep the bus waiting with the excuse that the license is fake or the bus does not have a fitness certificate while their real intention is to get some money out of the drivers. "Give him a Tk 100 note and all your papers become ok," complains Sharfuddin Ahmed, a regular passenger in Gulistan-Mirpur route.

"It's unbelievable the amount of time we have to lose due to traffic jams," says 40 plus Abdus Salehin, standing at Ababil bus counter in a long queue that has taken the shape of a snake. It's 5.30 pm and the entire Motijheel area is flooded by home bound people. Salehin, a chemical engineer at the BCIC, grows impatient as he waits for the Uttara bound bus. "I bought the ticket 10 to 12 minutes ago and there is no bus in sight," he says despairingly adding that sometimes the wait for a bus may run into nearly an hour, as he won't be able to get on the first bus. "There are about 35 to 40 people in front of me," he says after a quick head count, and explains each bus takes at best, 15 passengers from here which means his turn will not come until the arrival of the second bus. "On an average I have to wait for 20 to 50 minutes just to make it to the bus," he says.

No doubt it is a lot of time, especially when one is dead tired after a whole day's work. Some people in the queue are seen reading the newspaper holding it in one hand while balancing the office bag with the other. "This is the second newspaper I am reading now. How else would you spend two hours waiting for the bus," Khorshed Alam, another middle-aged passenger discloses his ways of killing time.

But, things are worse for those who have to get on the bus from midways. Passengers who take the bus at its starting point can at least have a seat, but those who have to get on from Malibagh or Rampura in Motijheel-Uttara route have to stand all the way desperately waiting for a chance to scramble for a seat left vacant by a passenger.

Commuting troubles are a universal phenomenon that cut across all classes of commuters. Commuters who have to endure the horrific suffering of travelling by local buses mainly for monetary reasons are not the lone sufferers though. Those who have the means to spend some extra money to travel by rickshaw or auto-rickshaw or cab have their own set of problems. Commuting troubles are a universal phenomenon that cut across all classes of commuters. Commuters who have to endure the horrific suffering of travelling by local buses mainly for monetary reasons are not the lone sufferers though. Those who have the means to spend some extra money to travel by rickshaw or auto-rickshaw or cab have their own set of problems.

One common problem with any of these choices is that they are seldom available when you need them the most, especially during office hours. Mechanical engineer Saidul Islam, who works for Kleanheat Gas, usually travels by autorickshaw or cab to his workplace at Banani from Gopibagh. "When I come out in the street at around 8.15 or 8.20 in the morning, there is no autorickshaw or cab in sight. Very often I have to take a rickshaw to Hatkhola roundabout and even beyond to catch hold of a taxicab. And often, sensing the urgency, they ask for more than what the meter would read," he says.

Again you don't even know exactly where you can find a cab, says Syeda Mustari Alam, who lives in Jigatola and works at BRAC's head-office in Mohakhali. "I usually come to Jigatola bus stand to catch a taxi, but sometimes I seem to be waiting for ages and still there is no taxi. I think there should be some cab stands, so that when they are not available on the road one can go to a designated place in search of one," she observes. She also points out that most of the cab drivers drive recklessly and would not bother to pay heed when asked to be cautious by passengers. "I try to pick elderly drivers," she adds. Besides, cab drivers also have a knack for not wanting to go to certain destinations giving flimsy excuses. Like they usually will refuse to go to Mirpur or Cantonment or Old Dhaka. They are extremely reluctant to go short distances, sometimes not even for extra money, though they are supposed to go anywhere they are asked to.

|

| A large number of commuters, especially those belonging to middle and lower middle class, depend on buses braving all odds. |

Those who are fortunate enough to have their workplaces within a distance that can be covered by rickshaw also face similar problems. "From 8.30 to around 10 am onwards they (rickshaw--pullers) would not go to Motijheel or to any place through Motijheel, because of the traffic jam " complains Aftab Ahmad, a junior officer in Mercantile Bank's Head office at Motijheel.

Many believe the main reason behind commuters' plight in Dhaka is the city's unplanned and unbridled growth. Commercial complexes have been built in residential areas. Dhanmandi alone is the address of around 40 educational institutions including schools, colleges and universities as well as around a dozen shopping malls. The result is impenetrable traffic jam. One just needs to pass through Dhanmandi from 1 to 3 pm when several thousands of homebound school-going children and their parents turn the entire Dhanmandi area into a virtual chaos. Dead tired from long rigorous school hours, the young boys and girls waiting in rickshaws and cars impatiently for the next intriguing knot of traffic in to getting eased, accompanied by their equally disturbed parents, make a sorry sight.

Commuting troubles have also affected the Dhakaites lifestyle; the Dhakaites are less and less inclined to go out of their houses. "I prefer sitting on my verandah or watching television than going out, sweating and gathering dust," Faisal Iqbal, a young marketing executive working for AKTEL, says. Among other reasons, community difficulties contribute to the diminishing social contact between people. "In our youth, visiting relatives' house often along with the entire family was a major part of entertainment, but things have changed now. I have not visited my younger sister's house for the last three and a half years though it is only 20 minutes rickshaw from my house," says 50 plus Azizur Rahman, a high official in Bangladesh Bank. "The very idea of going out just gets to my nerves", he ends.

Searching

for a Solution

Mustafa Zaman

|

To make Dhaka streets pliable dependency on private cars is to be contained. |

Dhaka is a concrete maze that lacks sufficient infrastructure to facilitate easy mobility for its dwellers. It is the commuters who suffer the most, as they confront the problem on a daily basis. There has been plans to increase the road surface and efficiency of the existing modes of transportation, but 10 years after the RAJUK's Metropliton Development Plan (1995-2015) that had been proposed way back in 1995, the situation remains the same. At present, newer avenues are being explored through creation of Dhaka Urban Transport Project (DUTP). The most important plan tabled is the provision of a metro-rail. There are other plans to mitigate the trouble of the commuters. In a phased programme the concerned authorities have joined forces and hired consultants to plan and implement Strategic Transport Plan (STP) that had started from 2004 and will last till 2024.

The DUTP was created to tackle the problems of mobility of the people living in Dhaka. It operates under the aegis of the Ministry of Communication and the Dhaka City Corporation (DCC). "DUTP is a project of the Dhaka Transport Co-ordination Board (DTCB). The board came into being in a special act passed at the parliament in April of 2001; it is tasked with co-ordination of transport in Dhaka," says Nazrul Islam, Professor, Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka, and honorary chairman, Centre for Urban Studies.

With the city mayor as the chairman of DTCB, and the secretary of the Ministry of Communication as the vice-chairman, it is steered by a committee of 23 members. The members are either chiefs of the concerned authorities or their representatives. The main tasks of the DTCB is implementing STP and its consultants are The Louis Berger Group and Bangladesh Consultant Ltd.

"The firms came up with a long-term strategy for Dhaka traffic, the main issue that they tackled was how the transport problem would be solved. An advisory committee was formed to review their plan, it was a high-powered committee with 32 members," informs Islam.

|

Experts feel that a separate lane for rapid bus service may

only provide a short-term solution. |

The main recommendations of the consultants were "delegated bus lane and 'pedestrian first' policy". "The main proposal was that a lane would be created for Bus Rapid Transport System (BRTS), it would be an imitation of the Bogota model," Islam points out.

The advisory committee was to review the strategies that the consultants put forward; Islam himself is one of the members of this committee. Prof Jamilur Reza Chowdhury, Vice Chancellor of BRAC University, is the chairman of the committee. He is in favour of the metro-rail and its early implementation. "We are pressing for an immediate feasibility test. In the STP the consultants have put a lot of emphasis on BRTS. I think the cost of BRTS has been underestimated, and the existing roads are too narrow for designating a separate lane for this system to work," says Chowdhury. He stresses the fact that it is the responsibility of the consultants to take the idea of metro-rail seriously and take steps to expedite the process.

Islam as well as the rest of the members of the advisory committee was happy about the plan of having BRTS, as long as it did not remain the only option. For them having a separate lane for speeding buses was a partial solution to the overall problem of traffic management. As for the 'pedestrian first policy', they were in agreement with the consultants, as they all acknowledged that Dhaka was a city where a major portion of the office-going public reach their workplace on foot. The advisory committee was overtly critical on the point that the long-term strategy to manage Dhaka traffic regarded BRTS as the only solution. "Their plan hinged completely upon roads, overhead expressways. We pointed out that their plan did not include metro-rail. In a city of 10 to12 million people, which will, in next 20 years, stand at 30 or 35 million, we can't exclude the idea of metro-rail if we are to facilitate the transport service," Islam points out.

"The consultant firms were not happy about incorporation of metro-rail. They relied solely on BRTS. But BRTS can provide a short-term solution to the problem," says Islam. It was at the insistence of the advisory committee that the consultants incorporated metro-rail in their strategy.

As for the pedestrian first policy, the advisory committee was happy to have regarded it as one of the most important features of the strategy. "Dependence on private automobiles has to be reduced to facilitate smooth mobility of commuters," Islam says. He hastens to add that 60 percent of all journeys to work is on foot. "A huge workforce belong to the garment sector.

Near about two million garment workers reach their workplace on foot, had this been brought into consideration, the footpaths would've been wider and in better condition," adds Islam.

|

| The city needs a "Pedestrians First" policy as sixty percent of city dwellers walk to their workplace everyday. |

"It is in the cantonment area where footpaths are always in proper condition, and where it is being used appropriately. In other places lack of proper walkways or ill-maintained footpaths force the garment workers to walk on the roads," Islam points out. "There should have been wider footpaths in Dhaka. Even in Kolkata there are footpaths as wide as 16 feet. And in some Scandinavian cities, where pedestrians are few, there are footpaths that are very, very wide," Islam points out.

Chowdhury feels that immediate steps should be taken to make Dhaka's road pedestrian friendly. "Footpaths have been taken over by vendors, and in places there are encroachers who have put up structures. These have to be removed for a sound management of the walkways," he says.

In Dhaka the withdrawal of rickshaws from major thoroughfares had a principle behind it, it was to be replaced by faster, cheaper public transport with larger carrying capacity. However, Dhaka still remains a city that pathetically lacks proper public transport system. Even in the STP the consultants pointed out that "Dhaka is perhaps the only city of its size without a well organised, properly scheduled bus system or any type of mass rapid transit system".

For Dhaka there is no alternative to an integrated transport system. Islam believes that the waterway that had been planned, the metro rail that had been proposed by the advisory committee, and even the non-motorised vehicles like rickshaw that ply in the connecting lanes would have baan a part of the matrix.

The road surface, according to an estimate put forward by Islam back in 1976, is eight percent of the total surface area of Dhaka. In an integrated system, with waterways and metro-rail, the need for roads will not be that great. Still Islam estimates that the road surface in Dhaka should be more than 15 percent. "If we are solely dependent on roads, then it must be between 20 to 25 percent. But it also depends on what kind of vehicle we are to use. With the big and medium-sized cars on the road, we need wider roads, when our policy should've been to use smaller cars," says Islam.

Before the work for metro-rail gets started, the main task facing the relevant authorities is to build the already proposed link roads and by-pass roads. "The major defect in the transport network is the absence of link roads between eastern and western part of Dhaka. And the by-pass roads that are in the pipeline must be implemented very rapidly," opines Chowdhury.

|

| The city needs a "Pedestrians First" policy as sixty percent of city dwellers walk to their workplace everyday. |

As for the ten new roads that had been planned by Razuk as far back as in 1995, only one had been completed in the last ten years. The widening of the roads too has not seen any headway. An executive engineer of zone eight of the Dhaka City Corporation says that there were plans for building four link roads that had not been implemented. "Three of which was in the RAJUK Master Plan," he says. The authorities responsible for implementation of these roads have shown no interest in following the RAJUK Master Plan. The concerned engineer believes that the higher authorities have not given directives to build the roads because they entail huge expenditure.

However expensive it is to turn Dhaka into a commuter friendly city, the strategies must be governed by the need of the public, not by the expenditure that the projects entail. In the STP proposed by The Louis Berger Group and Bangladesh Consultant Ltd the final design and financing plans for the first metro line begins in the 2010 to 2014 phase. The experts feel that the work of metro-rail must begin immediately. As Prof Islam has pointed out, Dhaka needs an integrated system of traffic, where even the waterways would be in proper use to facilitate mobility of the city dwellers.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |