|

Cover

Story

An Uncertain

Homecoming

Mustafa Zaman

|

They are back in their own country, but are they at home? |

After the UNICEF initiative, a ban has been slapped on the use of children as camel jockeys by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) government. Children who were once camel jockeys are now returning to their home. However, while they were in the land of the oil, they not only lost their childhood but also their language. Most ex-camel jockeys speak Arabic and Urdu, the languages they picked up from their employer and the majority workforce during the time they were employed.

Now that the days of being camel jockeys are over, the mature boys are more worried about their future. They are fretting over the prospect of making a living in a country where they feel like strangers. As for the authorities that joined hands with the UNICEF to repatriate these children to Bangladesh, their home country, they have chalked up reintegration plans. And the UAE government too will pay a certain amount as compensation for their lost childhood. On the backdrop of official endeavours SWM examines the quandary that these returnees are in while back in their own land.

|

| Parveen had had only two children when she went to Dubai, three more boys and a girl were born in Dubai |

A bunch of children were playing cricket on the front porch of a building. The scene had no such implications that would render it unusual in the eyes of the passers by. With shrinking open fields in Dhaka, one of the most common scenes of urban life is children playing in an improvised space. However, the children who were playing cricket on September 26, in front of Proshanti, the shelter home of Bangladesh National Lawyers' Association (BNWLA) at Agargoan, were a different bunch altogether. Their appearance gave no clue that would make any onlooker realise the anomaly. But, once their calls to each other and cries and shouts were given a hearing it immediately dawned on any unsuspecting spectator that these children were speaking in Urdu.

In fact Urdu is their lingua franca. They use it among themselves as well as while communicating with their Bangla-speaking counterparts. The children belong to a whole new category, -- "repatriated camel Jockeys". They have lost their mother tongue in the land where they were trained and used as camel jockeys. But while in the job they picked up Arabic, the language of the employer, and a kind of Urdu that is over-laden with Hindi expressions, the language of the majority of the work force.

Kamal, whose real name is Monjur, claims that he is 18 although he does not look more than 16. He is one of the 94 camel jockeys who were rescued from Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and repatriated to Dhaka in phases in the last two months.

Kamal is the given name under which he travelled to UAE and worked as a camel jockey. He left Bangladesh, his home country, eight years ago at the age of seven. Since then his life was fully entwined with camel race. It was a middleman who took Kamal along with him assuming the identity of his father. "I am not at all happy to be back. It is during training that all sorts of accidents happen, after the training period is over everything goes along just fine," Kamal points out. His enthusiasm for being a camel jockey is unmatched by any one else among the children who were passing their time playing at the BNWLA shelter home.

|

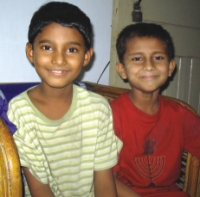

| Ronni (left) and Kamal (right), the repatriated ex-camel jockeys, worry about their future in Bangladesh. |

Ronni, whose real name is Babul, is not as impassioned about his past as a camel jockey. He is glad to be back, but he too says it with certain discomfort. "We are happy as well as unhappy. Happy because we will be meeting our parents here, unhappy as we are clueless about what we will do in this country" he says in his nonchalant Urdu. He claims he is 17; he looks more like 15.

Ronni went to Dubai when he was only three years old. "I have been a jockey for the last 12 years, but the amount of money I used to earn never reached my real father and mother, as the false mother who accompanied me to Dubai used to take away a major portion of it," he laments.

Ronni is not all that elated about the fact that he is back home and he will never have to be a jockey again, or do chores relating to the tenting of camels. But his view of the camel race is not that lighthearted either. "I have seen one or two children getting killed or being seriously injured every year," he gravely remembers.

Kamal and Ronni, the two teenagers, now seem way too pragmatic in their approach to life. Perhaps the long stay abroad while engaged in a life-threatening yet income-generating work has had an effect on their psyche. Their main worry now is whether they would be able to find work in Bangladesh. Both of them are willing to go abroad again just for the money.

|

| Rescued camel jockeys enjoy some television at the shelter |

Shohag is another 15-year-old who worked as a jockey for the last five years. He recalls the harrowing training sessions. "They used to wake us up around two or three in the morning and it was not until 11 or 12 at noon that we rode on camels," remembers Shohag. He too is looking at his future with trepidation. "If it so happens that I don't like it here, then I would try and find another job abroad," he adds.

Those who are most resigned to the ghastly circumstances that they were in before they quit being camel jockeys, are below 10. Yet they too can tell the difference now that they have gained freedom from this life-threatening game. Nur Hossain, a six year old, was in Dubai with his real parents. He is relieved that the days of being a camel jockey are over. Another seven-year-old named Jaman simply does not remember when he went to UAE. All that he recalls is that he used to ride the camel during the day. In his meek voice he says that sometimes he rode the camel twice in one day sometimes only once. He too is happy to have left his camel jockey days behind.

|

| At the shelter home of BNWLA, ex-camel jockeys spend their time reveling or snoozing while waiting to unite with their parents |

These Urdu and Arabic speaking children are waiting to unite with their parents. A few of them came back with their real parents. Most, who were taken to the Arab world under false identities, as children of middlemen or relatives, are eagerly waiting to meet their real parents after a long interval. Some of the parents have already contacted BNWLA and are waiting to receive their children after the relevant paper work is done. There are some whose parents are yet to be traced. The officials at BNWLA are eager to unite the children with their parents, yet they are extremely cautious about the identity of the real parents, as the cases of travelling to the UAE with fake parents have not been few. Figures released by officials of the interior ministry of UAE shows that around 49 percent of the smuggled children were brought by uncles, nine percent by cousins who pretended to be their parents.

The process of handing over the child to the parents is being done with the help of the police and the administration. "It is after the police verification report that we are handing over the children to their parents," says an official of BNWLA.

|

| Nur Hossain (left) and Jaman (right) are happy that the harrowing days of camel jockey is finally over |

But the reunion with their respective parents is not the end of the story. "After handing over the child to their parents we are unable to monitor the children from Dhaka, for that sole reason there is this Camel Jockey Community Care Committee (CCCC) that is to look after these children to ensure their reintegration into the community they once belonged," says the official.

CCCC a body headed by a woman member of the locality who is also its convener has five members -- the head of the gram Sarker, the imam of the local mosque, a teacher, an influential person and a

well-wisher of the child or a close relative. CCCC is entrusted with the job of monitoring the children after they have been handed over to their real parents.

"For each child the reintegration plan would be different, we are grouping the children according to age, and the economic state of the parents too is a factor in smooth reintegration. The plans are being implemented through CCCC. For the four to six year old children the plan of reintegration will be as lengthy as four to five years, for the older children the plan may extend for one year only," adds the official.

|

| A league of their own: Because of the common language they speak, ex-camel jockeys remain banded together while at the shelter home |

"We are getting the full support of the government mechanism. It is the UNOs or TNOs who are supervising the handing over of the children of their respective area, and the CCC too is a body that will work under their supervision. The home ministry's response too has been so prompt that the process of handing over is going on smoothly," says the official.

Shah Alam, social welfare officer of the BNWLA, remembers his last journey to Cox's Bazar. He accompanied six ex-camel jockeys, five of them from Ukia Thana and one from Teknaf. "We went straight to the TNO's office in every thana. He arranged for the parents and the local chairman and OC of the local police station to be present. It was in front of them that we handed over the children to their real parents," Alam testifies.

The first group of Bangladeshi camel jockeys arrived in Dhaka on August and many more have arrived home in phases. There are more children waiting in the "two special centres" located on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi. The centres are run by the UAE Interior Ministry, and the children there "are receiving necessary attention as preparations get underway for their repatriation," says a UAE official gazette.

According to the UNICEF estimate the number of camel jockeys in the oil rich Arab nation is nearly 200, while unofficial sources put the number at around a thousand. But not all children were used as jockeys; there are some who were engaged in tenting the camels, training them, cleaning their waste.

The exodus began right after the UAE government's decision on March 31 of this year, to ban the use of children below 16 years of age and 45 kg in weight to take part in camel races. The decision not to use child camel jockey was issued by the president of UAE Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan; it was followed by an agreement between UNICEF and the UAE government.

Many of these children have been trafficked with direct help from the parents. In fact each case could have been defined under the header of "economic migration" had it not been for the fact that under-age children were involved in earning the bread for their families. Still, the parents of those who accompanied their children to the land of the oil and camels, feels that it was their decision to continue to let their children be used in camel races. Sohrab Mia, of the village of Shapmara, in Raypura thana of the district of

|

| The sight of a picture of a camel still excites emotion among the children, few of them realise the danger that their occupation as camel jockey posed |

Narsingdi, went to Dubai back in 1996. He feels that it was on their own accord that they left for Dubai and when they were faced with the fact that their children would have to join the bunch who are used as camel jockeys they could not help but decide in favour of it. He blames the circumstances for his decision. He was promised by a middleman who arranged his expatriation that his two little boys would be given training to work in farms, and they would also be given education.

Sohrab Mia and his wife Parveen had only two boys then, Rubel and Shumon. "Shumon was only one year of age and Rubel was four and a half. At first the older boy was taken away by our employer Sayed Shah Alam Shomutee, and after three years the younger boy also joined work as a camel jockey," says Parveen. "Three more boys and a girl were born while living in Dubai. Among them the oldest Nuruddin, who is now eight years old, joined his brothers," she adds.

"We spent one lakh twenty thousand taka to go to Dubai, and when we reached our destination only then did we realise that our children would be used in camel races, which is a dangerous game. We found no other options but to relent. The money we have saved during our nine years stay in Dubai is not a huge amount, but it is enough to tide us over in the years to come," says Sohrab.

Rubel, who worked with the camel for nine years, cannot think of any other work to make a living. "I was

happy there. If I still could go to Dubai I would," he says emphatically. He is ready to overlook the small injuries that he sustained during his years as a camel jockey. But his younger brother Shumon's testimonies are laden with negative assertions. "I never got injured, but I never got to like the idea of sitting on a camel participating in race," he says.

|

| A learning session at the shelter home to familiarise the ex-jockeys with Bangla as well as Bangladesh |

For a family that once relied heavily on the children's earnings, Sohrab now is set to do his bid. He has got the visa to go back to Dubai for work. As for getting compensated, he only knows that the government of UAE has declared to pay a lump sum to each ex-camel jockey, but he is unaware of any plan of reintegration for the children. He and his wife have not even heard of the CCCC.

Shafi Uddin and Khorsheda Begum too are unaware of a committee that looks after the well-being of their children. The couple came back to their village home at Algee, of Raipura Thana in the district of Narsingdi. Their family spent "eight years and seven months in Dubai". They too were tricked into accepting the offer of turning their three boys into camel jockeys. "We were told that our children would be given Islamic teachings in madrasa, and would learn to tend gardens. But later we found out that they would be riding on camels; the idea horrified me and I wanted to come back home right at that moment," says Khorsheda. It was Khorsheda, accompanied by her three children, who went to Dubai first. Her husband joined them a year later, only to find that the opportunities for him to work were limited. In Dubai they were dependent on the earnings of their children. "For each child we were paid four hundred Dirham, and it was expensive in Dubai, so we needed the money badly," says Shafi. Their children, unlike most of the children who worked to tend the camel or as camel jockeys still speaks a little Bangla. In fact the jockeys whose parents were living in Dubai, had the chance to meet their parents once or twice a month, it helped to keep their mother tongue alive.

|

| Shafi Uddin and Khorsheda with three of their children at their home at Algee |

Shafi and Khorsheda left their two older sons in Dubai, who had already engaged themselves in other jobs, as they passed their camel jockey age. The family came back with five of their children, of whom four were born in Dubai. As for the CCCC's existence, this family is simply clueless. The only nudge they received was from the local chairman. "The chairman was asking us to start sending our kids to schools, as none of them attended any educational institution in Dubai," says Shafi.

Repatriation of the camel jockeys and their families is the beginning of a long process. Those who are involved in it have chalked out plans for the camel jockeys to be able to reintegrate them in a society about which they have little knowledge. However, the families like the ones in Shapmara and Aglee villages feel that the compensation money should be paid directly to them. They are willing to spend it to educate their children.

When the repatriation effort is on to send all under-aged camel jockeys home from the UAE, a new chapter is unfolding in the UAE that will change the characteristic of camel races forever. In Qatar, the world's first ever camel race has been staged on July 18 using

|

| Parveen with five of her six children at their home at Shapmara |

robot jockeys at Al Shahaniyya Camel Racecourse on the outskirts of the capital, Doha. It was a trial of replacing human jockeys with robots. The trial has proved to have been successful, and now the chapter of exploiting the children of the poor countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan or Sudan, from where majority of the children were brought in to be used as camel jockeys, has come to a close. With the returnees' welfare in mind, alongside the question of reintegration, there must be other plans where their language expertise will be called into use. One BNWLA official suggested that the government could take steps to employ them in countries where their fluency in Arabic would come in handy. As for now, schooling is the chief issue that must be addressed. The ex-camel jockeys as well as their siblings who were not involved in works were not sent to schools while they were on foreign terrain. Now that they are back in Bangladesh, the relevant authorities must intervene to make them feel at home as well as realise that their home coming has surely been for the better.

|

| Waiting to Unite: Most of the children were small when they were flown to UAE; now, at the shelter home they wait to reunite with their parents |

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |