|

Cover

Story

SHAHNAZ PARVEEN

Three-year-old Natasha sings with TV commercials and refuses to eat until she sees one of her favourite baby lotion ads on TV. Even at this early age she has learnt to identify and choose specific brands. While at the store with her mother she picks that favourite baby lotion from the rack and no other brand will do. If she cannot get her mother to buy the brand she wants she will go into a tantrum that may go on for hours. Sooner or later, her mother will relent.

For the advertising agency in charge of promoting the product, this is a huge success. Strictly from a sociological point of view, however, this phenomenon is directly related to the rise in the 'money culture' that places value on an individual based on what he or she possesses. For advertisers children represent a huge market for a whole range of products and advertisers really know how to grab their attention. Parents, meanwhile, in their earnestness to 'give the best to their child' may go a bit overboard with their generosity and give in to their endless demands. But by encouraging such materialism, are we really benefiting our kids?

Natasha's sister Nafisa is seven years old and looks like a life-size Barbie. Nafisa and Natasha share a room in their Banani apartment. Every corner of the room however, is stuffed with the knickknacks belonging to Nafisa. Pink Barbie backpack, matching tops and hairclips, that latest Cinderella Barbie or Barbie as Rapunzel, Nafisa has them all. Her next favourite are the Power Puff Girls and this has become the latest stuff that has hit the stores recently and she was the first one in her school to grab them.

Nine-year-old Nadvi, their older brother, has an insatiable appetite for fast food and drinks. Nadvi goes to one of Dhaka's reputed English medium schools. Everyday after school he must make a stop at his favourite ice cream boutique or take a short trip to Banani road no 11 for a feast of junk food. His father jokes that one day his expenditure on junk food might exceed the cost of his education.

|

| Toys from the Bayblade cartoon have become the latest craze. |

Natasha, Nafisa and Nadvi (not their real names) represent the children of today. They also represent another important aspect of contemporary lifestyles. Children represent a huge market. When it comes to spending money on consumer goods, marketing experts never underestimate the power of a whining child like Natasha. For them, Natasha, Nafisa, Nadvi are the 'evolving consumers'. Marketers have discovered the intriguing fact that it is very well possible to sell to children. They know that the child consumers of today are the largest and fastest-growing market.

Children represent three different markets. Direct spending by children is one of them. Children all around the world spend millions as pocket money on the things they desire. But children also influence the spending pattern of their family. They represent a third major market, and perhaps the most significant, as it is the future market. In Bangladesh, direct spending by children is limited, the third category looks very promising, however, the second category is probably more significant and cause of concern.

Children can often recognise brands and status items by the age of three or four, before they can even read. They begin to ask for things that they see and make connections between television advertising and store contents. They learn how to get parents to respond to their wishes. Whether it is through sulking or whining or even screaming almost all kids are able on a regular basis to persuade Ma or Baba to buy something for them.

"Apart from the basics that we provide as parents my daughter obviously influences our spending pattern. Whenever we are at the mall she asks for that latest toy, trinket or outfit that she has seen being advertised on TV or which her friends at school have," says Afsana Parvin working at a local NGO. "Because she is so young it is difficult to explain the pressure it creates on parents. And she is the only child so it is hard to say no," Parvin adds. "Apart from the basics that we provide as parents my daughter obviously influences our spending pattern. Whenever we are at the mall she asks for that latest toy, trinket or outfit that she has seen being advertised on TV or which her friends at school have," says Afsana Parvin working at a local NGO. "Because she is so young it is difficult to explain the pressure it creates on parents. And she is the only child so it is hard to say no," Parvin adds.

"Kids these days ask for more because they are exposed to so many things now. When we were kids we were not exposed to all these advertisements. In fact, the media was very limited in our times," points out Dalia Arefin a bank employee.

With more and more couples (in the middle income groups) having fewer children, the urge to spoil them increases. "I have only one child and tend to give him whatever he asks for, even if it means forgoing something I want," says Laila, a primary school teacher. Minhajuddin Ahmed, a graphic designer, has two daughters aged nine and five. He thinks the demands by his children is making him spend a lot more money but he thinks that it is only natural that kids would ask for toys and stuff. At the same time he admits that he is not happy that his daughters spend so much time in front of the TV, then wishing they had the things they see being advertised.

It's a general phenomenon all around the world that children born today spend more time watching television than they spend in class. TV time sometimes even exceeds sleeping hours. Such prolonged hours in front of the TV plays a major role in forming the children's consumption pattern. Marketers and advertisers have identified long time ago that consumer habits and brand loyalties are formed when children are young and vulnerable. This consumer habit is most likely to be carried through to adulthood. Today the advertising industries are increasingly targeting their sales pitches directly at the very young, which leads to the development of a potential consumer. It's a general phenomenon all around the world that children born today spend more time watching television than they spend in class. TV time sometimes even exceeds sleeping hours. Such prolonged hours in front of the TV plays a major role in forming the children's consumption pattern. Marketers and advertisers have identified long time ago that consumer habits and brand loyalties are formed when children are young and vulnerable. This consumer habit is most likely to be carried through to adulthood. Today the advertising industries are increasingly targeting their sales pitches directly at the very young, which leads to the development of a potential consumer.

"My daughter is affected by the 'free gift culture'," says Dalia Arefin. "Being a child is not as easy as it used to be. Advertisement totally captures the mindset of our kids."

This 'free gift' culture is becoming an issue of concern for many parents. Another parent, Sultana Yasmin, says, "My son is very much affected by Cartoon Network. He is tempted by all the ads of the popular brand of chips offering 'free gifts', which is becoming a burden for me." Afsana Parvin adds "TV is always selling something to kids. There is Powerpuff Stuff, then Mermaid Barbie or the latest Bratz Doll (modelled after bratty young girls) and many more."

Sometimes certain advertisements target a wide age range-- adults, teenagers and children. The idea that 'more is good' is a popular advertising motto that encourages the idea of increased consumption.

Most parents interviewed are not happy about the marketing of food to children. Food advertising on TV is often for junk foods like chanachur, potato chips, juices, soft drinks and candies. Total airtime of these foods always exceeds commercials for healthy food. Fast food chains all around the world spend billions of dollars every year on advertising, much of it aimed at children. To directly target children, the fast food industry uses more than traditional commercials. Restaurants offer incentives such as playgrounds, contests, clubs, games, and free toys and other merchandise related to animation movies or TV shows. Most parents interviewed are not happy about the marketing of food to children. Food advertising on TV is often for junk foods like chanachur, potato chips, juices, soft drinks and candies. Total airtime of these foods always exceeds commercials for healthy food. Fast food chains all around the world spend billions of dollars every year on advertising, much of it aimed at children. To directly target children, the fast food industry uses more than traditional commercials. Restaurants offer incentives such as playgrounds, contests, clubs, games, and free toys and other merchandise related to animation movies or TV shows.

The 'free gift' marketing strategy has been there for generations in western countries. Now our part of the world is trying to catch up with this trend. Sultana Yasmin explains how it works. "One of the Bangladeshi potato chips company once offered a free toy. My son made me buy it eventually. But a few hours later I found the chips lined up on the balcony and the crows having a feast out of it. The scent of the chips was so foul and the taste was so awful that he made the birds eat the chips. He kept the toy only. It's really outrageous that they sell expired goods to our children luring them with toys".

|

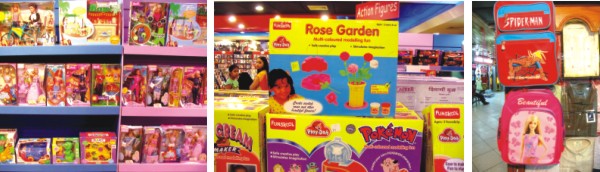

| Accessories and products with favourite characters on TV never fail to lure kids. |

Afsana Parvin thinks that the result of this aggressive marketing of food items which have high fat and salt content but very low on nutrients will only create a generation of obese individuals who are far from being healthy in the true sense. She relates, "Advertisement of junk food aiming at children is a bad influence. These foods are hardly health food. Kids are substituting proper, nutritious food with these."

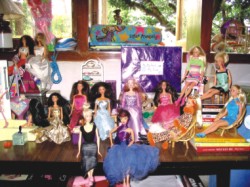

Marketers have long discovered an important trait about children: that they love to collect things. Back then it was marbles; today the craze is action figures, cartoon characters, video games, Barbies and Pokemon toys. Needless to say they are very expensive. Barbies can cost from TK 450 to Tk 2,500. Collected items are status items for kids. The business of action toys, Barbies or Pokémon cards and figures are totally dependent on this craze. Marketers just invent some cute characters; advertisers with their amazing gimmicks tell children that 'if you don't have it then you are not cool enough'. Children rush to the store. From the next morning, schools are flooded with that new and 'cool' thing.

The marketing strategy behind the Pokémon is simple. They created 150 Pokémon characters, then launched a marketing campaign called "Gotta Catch 'Em All", to encourage children to collect all 150 of the cheaply made, over-priced figures. Children all around the world including the youngsters of Dhaka made mums and dads spend thousands on Pokemon items.

|

There is no end to the range of toys available in the market. Advertisements make sure there is no end to the demands made by kids. |

Most of these collecting crazes however, are short-lived. The latest craze fades away and soon there is something newer and cooler. Dalia Arefin says her nine-year-old daughter Dipeeta was totally into Pokemon and Dragonball Z. Dipeeta says that Dragonball Z or the Pokemon fad is the thing of the past for her. Bayblade defeated all the other toys for now. Dipeeta thinks, "Tyson, the lead character of Bayblade cartoon, is the coolest."

Sultana Yasmin's 10-year-old son Shabab saves his money to buy toy cars. But toy cars are not his only passion. He is also passionate about Bayblade. "It is the latest craze in school," he says. Like his hero in the Bayblade cartoon on Cartoon Network, he wants to be a Bayblade champion when he grows up. Nadvi collects wrestling cards, his sister Nafisa is totally engulfed by the world of Barbies and Barbie accessories.

Because there is always something new, the novelty of the product quickly fades away from the current collection and kids move on to the next big trend, leaving behind boxes of discarded toys. This is when most parents think it is a total waste of money. "Buying the latest thing is a huge burden, because the craze always moves to the next 'cool' thing," says Afsana.

As kids are becoming more powerful consumers, marketers are targeting them even more blatantly. To make kids spend more, the advertisers are letting their imagination run wild using sophisticated psychological techniques. These include catchy jingles, dances, and cartoon characters, portraying adventures and mysterious worlds, always implying that their product will bring unbounded happiness.

Advertising can shape self-image and values of our children. Young children have difficulty distinguishing between advertisements and reality, and may not understand that ads are there to sell something for profit rather than with the pure intention to make kids happy. In fact, children watching TV often find the commercials more engaging than the programmes. Ads can distort their view of the world.

Seven-year-old Farita wants to look like the model in a popular shampoo ad and she thinks, to make it happen she must buy the shampoo, which is actually made for adults. The shampoo model is almost Farita's age who amazes her onscreen mother with sharp comments yet at the same time looks good too. Farita has beautiful hair just like the girl in the ad but she wasn't sure whether she was cool enough. She feels that she has to look like her. Her mother apparently feels the same and took her to the ladies parlour to get a hair cut just like the young model in the shampoo ad.

Advertising at its best can make people feel that "without their product, you're a loser" or their product makes them better than others. Kids are very sensitive to questions like "How many do you have? Do you have the Powerpuff stuff?" This creates an unhealthy environment. Kids in school engage themselves in competition. When kids from less privileged families demand what others are getting or what is being advertised and if they don't get them, there is the unnecessary sense of feeling let down. At school, where children from both very wealthy and middle class study together, a gap is created between those who have the latest 'cool thing' and those who haven't. They taunt each other for not having the "coolest stuff". Sometimes such advertisement can make kids feel bad about themselves when they can't have what is being advertised. It is making kids more materialistic.

Around puberty, in their early teens, children form their identities. At this stage they are highly vulnerable to pressure to conform to group standards and more. Teens are more influenced by peer pressure. Marketers take advantage of this. Advertisements shown on TV or billboards often imply "you are not cool enough if you don't have this product. Teenagers are also very rebellious, which is a natural part of the overall psychological and physical change. Advertisers sometimes use youth rebelliousness effectively to make a product popular. Cell phone companies make millions targeting teenagers and young adults through various marketing strategies such as special deals or promoting popular, colloquial jargon.

Advertising has become a type of curriculum, the most persuasive one all around the world. Kids are eager learners. Advertising is teaching children that buying is good and the solution to life's problems lies not in good values, hard work, or education, but in purchasing of more and more things.

The question finally arises whether kids today understand the value of money. The culture of consumerism, is it promoting spending over savings? The answer differs. Sultana Yasmin says, "Sometimes I explain that my budget for this month is kind of limited and my son understands." Dalia Arefin says it is she who buys all the stuff for her daughter willingly. Minhazuddin's daughters also understand their father's plea. Afsana Parvin however, says otherwise about her daughter. And Natasha, Nafisa and Nadvi always turn out to be the biggest spenders among the kids their age. The question finally arises whether kids today understand the value of money. The culture of consumerism, is it promoting spending over savings? The answer differs. Sultana Yasmin says, "Sometimes I explain that my budget for this month is kind of limited and my son understands." Dalia Arefin says it is she who buys all the stuff for her daughter willingly. Minhazuddin's daughters also understand their father's plea. Afsana Parvin however, says otherwise about her daughter. And Natasha, Nafisa and Nadvi always turn out to be the biggest spenders among the kids their age.

Some parents say they feel in conflict. They want to say no, but they don't want their child to be upset with them. "It is my fault because as a working mother I cannot spend enough time with my child. Out of guilt I buy lots of stuff for her. I try to keep her happy with all the things she wants," explains, Afsana Parvin.

Giving a fixed amount of pocket money, as is the case in western countries, say every week or every month, maybe a way to make kids understand the value of money. If they know that they know that they have only a fixed amount of money to spend, they may earn to save up to buy that special thing which will be of much more value to them.

Some parents think marketing to children should be carefully restricted. Others say marketing to children is unethical. In the western world, parents are fighting back. In the United States and Canada, a range of groups have appeared on the Internet with names like www.commercialfree.com or www.adbusters.com.

In the wake of worldwide debate about this issue Sweden and Norway have prohibited television advertising directly targeting children under the age of 12. Quebec in Canada restricted all television advertising directed at children under the age of 13.

"There should be policies about advertising to kids," says Afsana. "But ultimately parents are the ones who can control the situation by saying no. Parents need to learn about the adverse effect of ads first, then explain to their kids about the traits of marketing to children."

Minhazuddin Ahmed thinks all the ads targeting children are making them very good consumers but these kids, when they grow up, may continue to value material things and see them as measurements of success or failure in life.

A growing, even insatiable desire for material goods is always controlling the mind set of the children of today. "The way children are influenced by consumerism, it is obviously shaping our future as a materialistic society," indicates Afsana Parvin."Children from privileged backgrounds have no concept of the value of money. They just demand things that are ridiculously expensive and parents buy them without any resistance," says Laila. A growing, even insatiable desire for material goods is always controlling the mind set of the children of today. "The way children are influenced by consumerism, it is obviously shaping our future as a materialistic society," indicates Afsana Parvin."Children from privileged backgrounds have no concept of the value of money. They just demand things that are ridiculously expensive and parents buy them without any resistance," says Laila.

The market-oriented world of today sees kids through an economic lens. Children are viewed as an economic resource only to be exploited for greater profit. Experts say that people who are highly focused on materialistic values report less satisfaction with life, seem less happy, have a higher incidence of unsatisfactory interpersonal relationships, are more prone to drug and alcohol abuse and contribute less to their community. These are the side effects of rampant consumerism. A healthy society raises children to be responsible citizens rather than just frenetic consumers. Unless we curb the influence of advertising on our children and our own tendency to overindulge them, we will be responsible for nurturing the 'money culture' that has taken over almost the entire world.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |