Literature

Pause and Effect

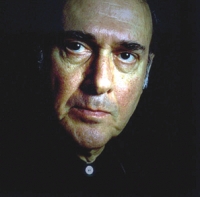

Harold Pinter, just awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, has dramatised the pain of being human for four decades, says ROBERT MCCRUM, providing a voice for our times - even in its distinctive silences

Literary prizes have a way of turning writers to stone. Now that Harold Pinter has won the Nobel, the latest in a succession of awards, he might seem more than ever at risk of becoming marmoreal. Mercifully, the writer himself is so zestfully alive, and so full of dangerous vitality, there is little chance of his becoming embalmed by fame.

In the search for a Harold Pinter you can relate to, the man himself is a wonderful source of self-revelation. There's one story, among dozens, told by Pinter against himself, that expresses an essential part of his character. In the search for a Harold Pinter you can relate to, the man himself is a wonderful source of self-revelation. There's one story, among dozens, told by Pinter against himself, that expresses an essential part of his character.

A supporter of the Sandinistas and a fierce opponent of US foreign policy, he was returning from Nicaragua in the mid 1980s. His route, perforce, took him through Miami. For Pinter, to have to overnight on the soil of the great Satan was a source of intense irritation, though unavoidable.

'So I got to Miami airport,' he says, 'and I saw a very big lady at the immigration desk. As I got into line, I said to myself, Now she's going to open my passport and say to me, "What were you doing in Nicaragua?" And I said to myself, I'm really looking forward to this because my reply is going to be, "It's none of your business."

'So I finally got to the desk and I opened my passport, and she said, "Are you the Harold Pinter?" And I said - totally thrown - "Yes." And she said, "Welcome to the United States."' He laughs.

Pinter has been looking for trouble and extracting drama from everyday existence all his life. As the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants he would confront anti-Semitic East End gangs. After the war, he was a conscientious objector. His parents tried to dissuade him. But his English master, whom Pinter reveres, told them: 'Don't try to change Harold. If he wants to go to prison, he'll go, whether you like it or not.' So he duly went to court and was fined 80 quid.

Recently, he has conducted an obsessive and magnificent campaign against the war in Iraq, and before that the Nato operations in the Balkans, suggesting that Blair should be 'tried as a war criminal'. Speaking of his formative years, he once remarked: 'I decided to go out on a chosen limb.'

Figuratively, he has been out there ever since, nourished by the fierce humour and visceral rage that reverberates so menacingly through every line he has ever written. You suspect that he has always been the Harold Pinter, the star of his own show, fiercely singular and intensely original, a true artist.

Like the greatest playwrights in the English theatrical tradition of which he is the finest living exponent, Pinter was a poet (and briefly a novelist) before he was a playwright. Almost all the themes that distinguish the early plays such as The Birthday Party, The Caretaker and The Homecoming are to be found, in sketch form, in his first novel The Dwarfs, a strange and lyrical fiction that evokes the life of a disaffected book-mad East End teenager roaming the streets of Hackney with his friends, a circle of like-minded would-be artists, most at ease with dossers and outsiders, in the postwar years.

A published poet, Pinter became a professional actor in his twenties, working in repertory during the 1950s under the stage name of David Baron. To this day, he still makes cameo appearances in all kinds of film and TV scripts, and he also performs in and directs his own plays. Like Shakespeare, he learned his craft in front of live audiences. A decade of repertory work might have inspired a career as a matinee dramatist. Not Pinter. His first play, The Room, left audiences and critics angry and bewildered. When asked what he was on about, the author is said enigmatically to have remarked: 'Look for the weasel under the cocktail cabinet.' A published poet, Pinter became a professional actor in his twenties, working in repertory during the 1950s under the stage name of David Baron. To this day, he still makes cameo appearances in all kinds of film and TV scripts, and he also performs in and directs his own plays. Like Shakespeare, he learned his craft in front of live audiences. A decade of repertory work might have inspired a career as a matinee dramatist. Not Pinter. His first play, The Room, left audiences and critics angry and bewildered. When asked what he was on about, the author is said enigmatically to have remarked: 'Look for the weasel under the cocktail cabinet.'

It sometimes takes a while for the theatre-going public to hear a new voice. Quite quickly, however, Pinter clicked with his audience. By the mid-Sixties his haunting, poetic dramas of down and outs and derelicts, and the generally dispossessed, were playing to packed houses.

Pinter's dramatic vision developed out of his admiration for Samuel Beckett, another Nobel laureate, who was also a kind of mentor to whom he would submit his early work. But Pinter's credo, expressed in The Homecoming, and perhaps more interrogative than Beckett's, was: 'Between the known, and the unknown, what else is there?'

Like Beckett, Pinter's dramatic vision is bleak and provisional, and his language is stripped to its essentials. 'One way of looking at speech,' he has said, 'is to say it is a constant stratagem to cover nakedness.' His famous pauses punctuate the painful interactions of humanity like silent bars in a great symphony.

Unlike Beckett, Pinter's dramatic landscape is recognisably English. Laconic and precise, attuned to the lethal nuances of English conversation, his dialogue is the perfect instrument for the exploration of the human condition in the late 20th century. 'Pinteresque', a word now in the OED, has come to mean an intoxicating cocktail of menace, erotic fantasy, obsessive jealousy, family hatred and mental disequilibrium.

Although his work is performed in translation all over the world as a voice for our times, he remains both profoundly English and at the same time at odds with his society. For instance, he adores cricket, both as player and spectator. Typically, he finds it 'a wonderfully civilised act of warfare'. Strangely, for an instinctive rule-breaker, he accepts the rules of the game, claiming that there are 'good rules and bad rules'.

In the 1970s, cricket was a theatrical setting in which Pinter could relax. The game, he said was 'the greatest thing that God ever created ... certainly greater than sex, although sex isn't too bad either'.

As he came into middle age, Pinter's vision morphed into his mature masterpieces like No Man's Land and Betrayal, but the kind of artistic intensity that inspired his early work could not be sustained. In the 1980s, after his marriage to Antonia Fraser, the muse of his later years, he channelled his volcanic contrarian instincts into a farrago of political causes from anti-Thatcherism to the defence of Salman Rushdie. He joined CND, became active in PEN and campaigned for the release of prisoners of conscience. As he came into middle age, Pinter's vision morphed into his mature masterpieces like No Man's Land and Betrayal, but the kind of artistic intensity that inspired his early work could not be sustained. In the 1980s, after his marriage to Antonia Fraser, the muse of his later years, he channelled his volcanic contrarian instincts into a farrago of political causes from anti-Thatcherism to the defence of Salman Rushdie. He joined CND, became active in PEN and campaigned for the release of prisoners of conscience.

After more than a decade of theatrical silence, the plight of the Kurds in Turkey inspired a short play Mountain Language (1988), but Pinter's genius was not wholly suited to political drama. Since then, Pinter's voice has become more and more intermittent: Moonlight (1993), Ashes to Ashes (1996), and Celebration (2000). 'Good writing,' he says, 'excites me, and makes life worth living.' But he has found it hard to find the good words in the way that he used to, and he now says he will write no more plays. Next year, as part of the Royal Court's 50th birthday season, he will perform in Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape.

His most recent publication, War, a collection of eight poems and a polemic, took him back to his youthful obsession. At the same time, now in his seventies, after the painful readjustment of the 1980s, he has emerged as that very rare creature in British cultural life, a public intellectual with unrivalled rhetorical gifts.

In 2003, he was diagnosed with cancer and nearly died. Perhaps his rage discouraged the grim reaper's attention. He has (thank God) hardly mellowed, but admits to being 'more conscious of death' and 'more detached'. His main concern now, he says, is 'simply to survive. To remain. To remain here.' Although he is much too modest to talk about this, he probably knows, what the Nobel committee has recognised: that his work will always remain, like a beacon.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|

| |