|

Cover

Story

Jamdani's Jamdani's

Struggle

to Survive

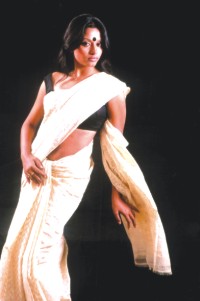

Jamdani, with its majestic designs said to be of Persian origin, has always been the most expensive product of the Dhaka looms. A legacy of the rich Mughal culture, there is something quite regal about the Jamdani. The diaphanous material in subtle shades adorned with elaborate, symmetrical patterns in tasteful colour combinations hint at the sophistication and taste of the wearer. Indeed the Jamdani is meant for the discerning, elegant woman who wears it only on special occasions.

"Jamdani is for the well-to-do, the middle class and the rich; it used to be patronised by the educated classes," says Monira Emdad, CEO of Tangail Sharee Kutir, a champion of this exquisite garment. Jamdani is also an intrinsic part of our national heritage and is representative of our identity. As an industry, however, Jamdani production is on the decline and the hard-working, highly skilled weavers are finding it hard to keep the tradition of their forefathers alive in a market that is not expanding. "Jamdani is for the well-to-do, the middle class and the rich; it used to be patronised by the educated classes," says Monira Emdad, CEO of Tangail Sharee Kutir, a champion of this exquisite garment. Jamdani is also an intrinsic part of our national heritage and is representative of our identity. As an industry, however, Jamdani production is on the decline and the hard-working, highly skilled weavers are finding it hard to keep the tradition of their forefathers alive in a market that is not expanding.

AASHA MEHREEN AMIN and KAJALIE SHEHREEN ISLAM

JAMDANI weaving is somewhat like tapestry work, where small shuttles of coloured, gold or silver threads are passed through the weft. Designs range from the "butidar", where the entire sari is scattered with floral sprays, to diagonally-striped floral sprays or the "tercha" and a network of floral motifs called "jhalar". Today, however, price constraints have forced weavers to simplify their designs.

Ruby Ghuznavi, proprietor of Aranya, says that enlarging Jamdani designs in the form of larger "paars" or borders and so on is one of the biggest dangers. "Jamdani designs were always very fine," she says. "But they take a long time to make and are very expensive so weavers today tend to take short-cuts." It is not the fault of the weavers, however, says Ghuznavi, but the designers. In the process, however, the weavers lose the patience and ability to do finer patterns. A good Jamdani takes two to three months to be woven, she says, and a simpler one, about six weeks. Ruby Ghuznavi, proprietor of Aranya, says that enlarging Jamdani designs in the form of larger "paars" or borders and so on is one of the biggest dangers. "Jamdani designs were always very fine," she says. "But they take a long time to make and are very expensive so weavers today tend to take short-cuts." It is not the fault of the weavers, however, says Ghuznavi, but the designers. In the process, however, the weavers lose the patience and ability to do finer patterns. A good Jamdani takes two to three months to be woven, she says, and a simpler one, about six weeks.

"You don't need to own 20 Jamdanis," stresses Ghuznavi. "Own one, but a good one. It's like an heirloom." Jamdanis should be given the high value they deserve without any compromise, says the designer.

Aranya, says Ghuznavi, is trying to revive old designs, like the "kalka", an age-old pattern. It is doing so by collecting old Jamdani saris, and, where not available, photographs and photocopied pictures of old designs from museums and collectors.

Recent trends of embroidering Jamdanis or putting Jamdani "paars" on silk saris is "unforgivable", says Ghuznavi. "You're destroying a heritage," she says.

Aranya is doing a lot of work on product development, says its owner. It is transferring Jamdani onto, say, men's panjabis and dress material, for clothes are ultimately what sell. But they keep the designs intact. In addition, Aranya uses its own cotton and silk, guaranteeing that it will not tear. On top of it all is, of course, Aranya's forte -- vegetable dye.

|

Aranya's cotton indigo Jamdani with "tercha" pattern exemplifies the effort to revive the classic Jamdani. |

"Though many fashion houses claim to be using vegetable dye," says Ghuznavi, "few actually do." She mentions Kumudini as probably being the only other house to actually be using vegetable dye, while Aarong is about to revive it. Vegetable dye is important for the environment as well as generating employment, says Ghuznavi. "But most people aren't bothered with these things, regarding them as 'someone else's problem'."

Aranya basically uses different, bright shades of blue, green and red. "Because Eid in recent years has been during the winter, you can play with the fabrics and the colours," says Ghuznavi. Aranya has used a lot of blue this year in its attempt to revive indigo. "Indigo must be marketed more pro-actively and aggressively," stresses Ghuznavi, "and people must be taught how to use it. It would be criminal to lose indigo for the second time," she says.

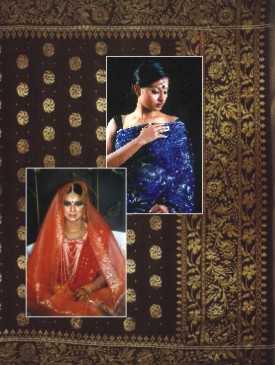

Although there have been attempts to introduce modern patterns in Jamdani, Monira Emdad says that this is unnecessary. "There are over a hundred traditional designs and they are beautiful. Why would we need to bring in new designs?" Designs have curious names "ichar thang" (shrimp leg) "dubla jaal" (like a fish net), "phul tesri" (floral pattern), "jalar naksha" (all over pattern) and so on. Emdad believes that it is important to revive these classic patterns that are part of our heritage. She does, however, experiment with different ideas. Her latest creations include an off-white khadi thread Jamdani with elaborate designs that is priced at around Tk 40,000. The reason why it is so expensive is that it has been made from fine khadi yarn from India as the local khadi thread from Comilla is very thick. Emdad has also experimented with indigo. For her daughter's bridal sari, she designed a gorgeous red Jamdani with pure gold and silver zari that took around four months to make. The price range of Jamdani saris is from 2,000 taka to as high as 50,000 taka, depending on the quality of the material and how long it has taken to weave the particular design. Although there have been attempts to introduce modern patterns in Jamdani, Monira Emdad says that this is unnecessary. "There are over a hundred traditional designs and they are beautiful. Why would we need to bring in new designs?" Designs have curious names "ichar thang" (shrimp leg) "dubla jaal" (like a fish net), "phul tesri" (floral pattern), "jalar naksha" (all over pattern) and so on. Emdad believes that it is important to revive these classic patterns that are part of our heritage. She does, however, experiment with different ideas. Her latest creations include an off-white khadi thread Jamdani with elaborate designs that is priced at around Tk 40,000. The reason why it is so expensive is that it has been made from fine khadi yarn from India as the local khadi thread from Comilla is very thick. Emdad has also experimented with indigo. For her daughter's bridal sari, she designed a gorgeous red Jamdani with pure gold and silver zari that took around four months to make. The price range of Jamdani saris is from 2,000 taka to as high as 50,000 taka, depending on the quality of the material and how long it has taken to weave the particular design.

|

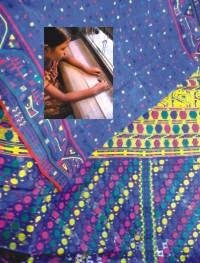

| Some weavers have spent their whole lives weaving gorgeous, expensive Jamdani saris but still remain poor and vulnerable to fluctuations in the market |

SADLY, the Jamdani industry is a declining one. With a shrinking market and the long hours of labour required to produce the saris, Jamdani weavers are losing interest in the trade, so proudly nurtured by their forefathers.

At the Jamdani Village in Dokhin Ruposhi in Demra, just outside Dhaka, weavers are busy at the looms in spite of the drenching rain outside. Most adult weavers work as long as 18 hours a day with breaks for meals or prayers. The work itself is very laborious and requires extreme concentration. At the loom, two weavers sit side by side, usually an "ostad" or seasoned weaver and a "sharkit" or helper. The helper is an apprentice who starts learning the trade as a child and each step of this painstaking process has to be taught by the "ostad". The Jamdani Village was established by the government after independence to promote financial support to weavers.

An apprentice weaver starts when he or she is a child. The "malik" or owner of the factory has to pay Tk 20,000 to the apprentice, which must be paid up if the apprentice decides to leave the factory. It is a strange custom. If the apprentice is a girl then this money may be partially or fully waived when she gets married. An apprentice or helper must stay with the factory for at least one year. "If we can't give the money, sometimes the malik hits us," says a young helper. An apprentice weaver starts when he or she is a child. The "malik" or owner of the factory has to pay Tk 20,000 to the apprentice, which must be paid up if the apprentice decides to leave the factory. It is a strange custom. If the apprentice is a girl then this money may be partially or fully waived when she gets married. An apprentice or helper must stay with the factory for at least one year. "If we can't give the money, sometimes the malik hits us," says a young helper.

At one of the looms, Ibrahim and Kohinoor, married for seven years, are working together on a red on white "jaadu phool" sari. They have been working at the mill for three years. Before they used to weave saris in their own home and used to get the proper price for them; now they don't.

|

| The looms of Demra are busy even during Ramadan, belying the fact that the industry is on the decline. |

"Our fathers and uncles were all in this business," says Ibrahim. They never thought of doing anything else. Together, Ibrahim and Kohinoor earn Tk 4,000 which is barely enough to pay for the Tk 300 rent, school fees for their six-year-old daughter plus food expenses. "We can never save anything," says Kohinoor who does not want her daughter to enter this profession. "We don't get a fair value for our work, what is the point of writing all this, nothing will change." Children of most weavers in fact, do not want to enter this profession that requires sitting for such long hours. Many prefer to join garment factories, which pay overtime and where the hours are less.

At another loom, Muhammad Abdul Hai is weaving a "phul tesri" or floral design in a black and white with zari sari. He is assisted by his 12-year-old niece, an apprentice who is learning the art from scratch. Hai says that most taantis (weavers) are not given the proper value for their hard work, a sentiment echoed by all the weavers. A senior taanti or "ostad" earns about Tk 2,500 to Tk 3,000 per month. Junior weavers get much less, around Tk 1,600. At another loom, Muhammad Abdul Hai is weaving a "phul tesri" or floral design in a black and white with zari sari. He is assisted by his 12-year-old niece, an apprentice who is learning the art from scratch. Hai says that most taantis (weavers) are not given the proper value for their hard work, a sentiment echoed by all the weavers. A senior taanti or "ostad" earns about Tk 2,500 to Tk 3,000 per month. Junior weavers get much less, around Tk 1,600.

"We don't get enough income. We just somehow survive," says Razia Begum, who has been doing this for 16 years and has a 10-year old daughter who is already learning the trade. Her husband too is a weaver and works at home. She is working on a spectacular gold and white Jamdani with a "ponar jal" or fishing net design. Razia says that most weavers suffer from backaches due to the long hours.

|

| Tangail Sharee Kutir's khadi Jamdani uses the finest khadi thread. |

Abdus Samad, probably in his seventies, has been weaving Jamdani saris for some 50 years. He has been at this particular mill for two years. Before, he used spin saris in his own home. "But I couldn't find a helper to work with me," he says, so he joined the mill. His son and daughter both weave at home. Samad gets a weekly salary of 500 taka -- 200 taka less than he used to when he was younger and more efficient. Now, with his failing eyesight, the owner of the mill pays him less. Samad, however, gets almost half the price of the sari he weaves. "But still," he says, "we just get by, and at the end of the year, we are always in debt to the owner. But we don't have a choice; we have to work to survive."

Ali Haider, another senior weaver, says that although all his four brothers used to be weavers, at present he is the only weaver in the family. His brothers have moved to other more lucrative professions. Before Haider's family used to make Jamdani saris and sell them but over the years the family became poorer with Haider ending up as a worker in someone else's factory. A few former weavers have been able to make enough money to set up their own factories and hire other weavers to make the saris. These "ostad"-turned businessmen are much better off than they were before. But for most weavers, there is very little chance to save and they will probably remain hired workers until they die or retire.

Abdus Samad's helper, Anwara, is in her twenties and has been in the business the last 13 years. She even worked as an "ostad" before, but, not being able to find or afford a helper to work with her, became a helper herself at the mill. Ideally, says Anwara, she would like to work by herself and not for any owner. "But it's not possible," she says. "All this is very expensive and would probably cost some 7,000 taka," she says, pointing to the handloom. "We can't afford it." Abdus Samad's helper, Anwara, is in her twenties and has been in the business the last 13 years. She even worked as an "ostad" before, but, not being able to find or afford a helper to work with her, became a helper herself at the mill. Ideally, says Anwara, she would like to work by herself and not for any owner. "But it's not possible," she says. "All this is very expensive and would probably cost some 7,000 taka," she says, pointing to the handloom. "We can't afford it."

Behind Anwara sit her two cousins, Md. Ruku and Labony. Ruku has been weaving saris for 12 years and Labony for six. All three cousins give their earnings to their parents who spend it all, they say.

A somewhat disillusioned Labony, who has never been to school, says, "We will work here 'til we die . . ."

|

The younger generation of weavers is not happy with the long hours and low wages. Many opt for working in garment factories. |

THE most amazing thing about these Jamdani weavers is that they have little or no education to fall back on. Anwara, who studied in Class 1 for a while, points out, "People don't understand that they should educate their children. Whenever they're old enough, they put them to work to bring in money." Anwara says that the owners could educate the weavers if they wished. "We get off early on Fridays and Saturdays," she says. "They could give us some lessons then."

But despite lacking basic education, the weavers' brains are as astute as sharp mathematicians'. Every pattern, no matter how intricate, is etched into the weaver's mind and has been passed down from one generation to the next. The motifs are repeated with remarkable precision and there is hardly any inconsistency in the design. Nothing is sketched or outlined. The weavers just know the exact number of times to do a certain stitch to combine the yarns to come up with a particular motif.

Anwara shows a small photograph of a Jamdani sari with a more or less clear "tercha" design on it. "We can just look at a small picture like that and weave the design," she says confidently.

Abdus Samad, weaving saris for 50 years, has seen many new designs over the years. "Many designs have been developed," he says, "and they have improved too."

|

| The younger generation of weavers is not happy with the long hours and low wages. Many opt for working in garment factories. |

It's a long day for the weavers from 6 in the morning to 9 at night and they are happy to have someone to talk to, though their fingers don't rest for even a minute. "Our feet and backs become stiff," says Samad. Anwara says that they sometimes lie to the "ostad" and go for short walks around the compound. "He knows we're lying," she says, "but he also knows we need small breaks in order to work." Other than that, lunch hour is between 1 and 2 in the afternoon. "And you can't be late on mornings or they scold you," says Anwara.

"There is no peace," agree both Samad and Anwara. "We try to smile and be happy," says Anwara, "but we suffer a lot of hardship."

JAMDANI weavers use the finest Egyptian cotton. Even the silk thread used is 100 percent imported, usually from China and Vietnam. Monira Emdad points out that seri-culture or the cultivation of silk is practically non existent in Bangladesh now. "Before there was a little government project in Rajshahi but it was a failure. We need raw materials and a stable market."

|

Each pattern is woven with mathematical precision. The art has been handed down from one generation to the next. |

The Jamdani is something that is exclusive to our country, a symbol of our rich cultural heritage. With it is intrinsically entwined the lives of generations of weavers, artists who are struggling to keep an ancient tradition alive. But apart from the sentimentality associated with past glory, it must be recognised that the Jamdani industry can only survive if the market is expanded. Jamdani must be made more popular among the privileged classes and quality of the product has to be maintained to ensure an overseas market. Unless the demand for Jamdani saris is increased, the weavers will continue to suffer in terms of lower wages. Worse still, is that their children will not find it feasible to enter into a profession that pays so little. With fewer and fewer skilled weavers, an unstable market and lack of greater state patronage, the danger of losing this rich piece of heritage forever, is very real.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |