| Cover

Story

When Community Cares

Shamim Ahsan

Photographs: Biplab Zafar

The young lanky plants wet from the drizzle look greener than usual. Mehra rubs her wet face with the anchal of her sari as she carefully pulls off the four--foot high mahogany plants. The tiny mahogany leaves on the tender branches are glistening as the mild, soft raindrops seep into them. Mehra piles them in one corner of the rectangular nursery and says that she has received an order for 50 mahogany plants in the local market. "They will sell at Tk 15 apiece, and 50 into 15 is equal to Tk 750, of which my profit will be Tk 400 to Tk 450, " she says enthusiastically. The young lanky plants wet from the drizzle look greener than usual. Mehra rubs her wet face with the anchal of her sari as she carefully pulls off the four--foot high mahogany plants. The tiny mahogany leaves on the tender branches are glistening as the mild, soft raindrops seep into them. Mehra piles them in one corner of the rectangular nursery and says that she has received an order for 50 mahogany plants in the local market. "They will sell at Tk 15 apiece, and 50 into 15 is equal to Tk 750, of which my profit will be Tk 400 to Tk 450, " she says enthusiastically.

Exactly three years and seven months back Mehra had to do an altogether different kind of calculation. Deserted by her husband, Mehra with her four minor children, had to live on Tk 80 a month that she earned working as a housemaid. "Tk 80 would vanish in the first week and for the remaining days of the month I had to live on by borrowing and begging," Mehra recalls her desperate days. Many days the mother and four children passed having just one meal. The straw house where Mehra and her four children huddled together in could not protect them from the rains and cold. Now, tins have replaced the flimsy straw on her roof and she has extended her home with two more rooms and Mehra no longer has to worry about getting "three meals a day" for her and her children.

About five kilometres away from Rangpur town, an otherwise nondescript and small village named Bahadur Singh has seen extraordinary changes over the last couple of years. Life for about two dozen of the most distressed families of the village have changed from one of hunger and humiliation to that of prosperity and dignity. Mehra leads one such family. Netrokona's Shaharban leads another.

About 10km north to Netrakona town lies a small village named Purbadhola. The narrow snake-like earthen road has a pleasant shadow over it, courtesy of all sorts of trees that line up on both sides of road. Small ponds with translucent water mirror back the tall and lean betel nut trees and all on a sudden a vast lush rice field stretches out gracefully completing the tranquil scene. But amid this image of beauty, one also inevitably catches sights of obvious poverty. Naked children, ramshackle huts and villagers wearing old and torn clothes come in sight with disturbing frequency. Towards the middle of this poor village lives Shaharbanu with her only son and three cows.

|

| Brac programme organisers regularly meet TUP participants to make them aware of vital social issues like dowry, child marriage, divorce and healthcare as well as water-borne diseases. |

Barely two years into her marriage 17-year-old Shaharbanu's husband Hazrat Ali took a second wife and subjected Shaharbanu to all sorts of physical torture to drive her away from home. But holding her 10-month-old son Rubel tight, Sharbanu clung on to her husband's house bearing with all sorts of disgrace and humiliation, because as she puts it, "I had nowhere to go to". Hazrat suddenly died and Shaharbanu's last consolation that she at least had "a husband" was gone. The mother worked as a maid in a household and the son roamed around the rice field picking up grains of rice left behind, plucking unknown leaves from nearby bushes and fishing with the lower part of his lungi. "Our main meal consisted of boiled kachu and during the rainy season shapla doga," recalls the mother. Bad days seemed to be over when 16 year-old Rubel went to Dhaka and joined a rod-making factory. But Shaharbanu's happiness met a sudden and cruel end when Rubel lost his right hand in a factory accident. The mother sold her only material wealth, her vita for the son's treatment. Rubel recovered, but was incapable of any work. Losing the only piece of land they owned the mother and the son were now living in one corner of the cowshed in their neighbour's house. Around a year passed; then one day BRAC came along.

Pointing to the cows that were having their lunch of cow-feed mixed with water, Shaharbanu shyly introduces them one by one -- the white one Raja, the slightly brownish Rahim Badsha and the new born Babu. The elder two gives around three kgs of milk which she sells for Tk 40.

Sharbanu also received a stipend of Tk 300 per month in the first year. Over the last two years she has managed to save Tk 1500 with which she set up a grocery shop for Rubel.

Mehra built her fortune on a nursery, close to her home. The nursery built on a 56 decimals land, is divided among eight poor rural women of the village, with 7 decimals for each of them. The rectangular nursery fenced by stout bamboo sticks is thickly populated

|

Fighting fate, with a little help |

with a whole variety of plants. As Mehra ambles along the narrow path that vertically divides the nursery, she caresses the tiny, tender leaves, trembling in the breeze, and introduces each of them -- mango, jaam, olive, aamloki, neem, Korai, arjun, hartaki, boira, eucalyptus etc. Mehra points out that prices of plants vary from each other, with the expensive ones like aamlaki and eucalyptus selling at Tk 20, hartaki, boira at Tk 10 while the cheapest ones like neem at Tk 2. At present there are around 8,000 plants and if they sell at Tk 4 on an average, the total turnover will be Tk 32,000. Her investment was Tk 10,000, which leaves her with a net profit of Tk 22,000. Aliza, Meena and Shamsunnahar, who live in the same village, have also been engaged in nursery cultivation. With an annual income of about Tk 20,000 they are no longer the hapless women for who even three meals a day were a dream. They are now confident, self-reliant women, who are not only able to meet the barest basic needs of their families, but have earned a respectable position in the society.

Mehra's financial independence with a secure future income has lured her opportunistic husband back to her. She is now planning to lease 10 decimals of land next year where she will grow another nursery. Aliza, who had stopped sending her 12-year-old son Rajjab Ali to school and engaged as a helping hand at a local tailor shop, is now once again sending him to school. "I will make him a doctor," she says. Meena has married off her two daughters. Shamsunnar has set up a grocery shop in the local market and her crippled husband who had been a burden for her is now engaged there and supplementing the family's income.

|

| Once hapless and miserable these poorest rural women now dream of a better future |

How have these women changed their fates so dramatically? It was due to a unique programme BRAC undertook back in 2002, called "Challenging The Frontiers Of Poverty Reduction--Targeting The Ultra Poor (CFPR-TUP)". Over the last three years by 2004, the programme has seen some 40,000 of the poorest families across 13 districts-- Rangpur, Kurigram, Nilphamari, Madaripur, Netrokona, Kishoreganj, Gopalganj, Sirajganj, Rajbari, Thakugaon, Lalmonirhat, Gaibandha and Panchagarh (these districts were selected in line with the Poverty Map worked out jointly by the government and the World Food Programme)-- coming out of the curse of poverty and aspires to see the same change in fate for a total of 70,000 families by 2006.

Poverty sells well in a country with around half of the populace living under the poverty line. Over the last two decades numerous local, national and international NGOs have brought millions of dollars to get this huge poor population out of the poverty level. Over the last decade or so, the much talked about, internationally recognised micro-credit programme conceived by Prof Yunus , which has been copied by many other NGOs as well, has had some success. But, some 31 percent people, who are bracketed as 'ultra poor', have somehow largely been bypassed by all these efforts, continue to live in abject poverty.

It is in this context that Brac took up this CFPR-TUP programme under which the poorest rural women would receive physical assets like livestock and nurseries for enterprise activities as well as training, some initial stipends and healthcare. Poor women, because extreme poverty has a clear 'gendered face' they are mostly women, dispossessed widows, who are often victims of child marriage; abandoned wives, who are the victims of polygamy or dowry. BRAC uses its own indicator to select the poorest of them, like the ones who live on begging, who have no land or any other income generating sources .

|

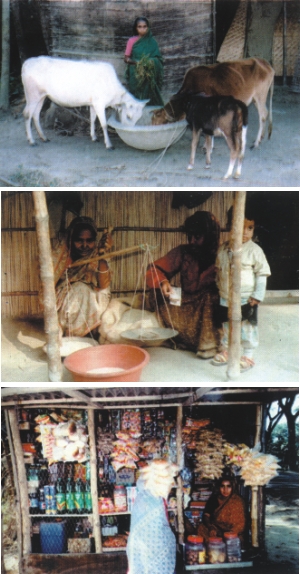

| Some of the TUP members Netrokona's Shaharbanu rearing cows, Nurjahan in her grocery shop and businesswoman Bulu. |

The most distinguishing feature is asset transfer, which is provided absolutely free. A particular recipient can choose from six different enterprise activities poultry, goat rearing, cow rearing, vegetable cultivation, horticulture nursery, and non--farm business. If one chooses poultry she is provided with 54 chickens, a cage, one year's poultry feed. Along with that a rigourous training programme over the two year programme cycle period plays a vital role in making the programme a success. Those who choose vegetable cultivation is provided with 25 decimal of land plus all other inputs necessary for the business; the ones who select cow--rearing are given away two cows, cow feed, vaccines, medicines etc. Then those who show interest in a wage employment, Brac has set up for them shoe factory, sanitary napkins production centres, bakery etc. Mehra, Aliza, Meena and Shamsunnahar of Bahadur Singh village chose nursery and each of them was provided five thousand seeds, 7 decimal of land, necessary fertiliser and all other inputs required for nursery cultivation. The participants are also provided with a daily stipend of Tk 10 to Tk 30 until they start to earn from their respective enterprises.

After being incorporated in the TUP programmes these poor rural women have not only changed their financial state; they have also learned to look after their own health as well as their children's and have installed tube-wells and sanitary latrines in their houses. Besides, Brac's programme organisers (POs) also hold regular meetings with the TUP members and talk about 10 issues of great social significance like marriage registration, child marriage, dowry, divorce, family planning etc.

The concern that these assets may be vulnerable to theft and damage prompted Brac to create a committee with the village elites by the name of Gram Shahayak Committee (GSC), later renamed as Gram Daridrya Bimochone Committee (GDBC) or Village Poverty Alleviation Committee. The main intention was to protect the assets and to engage them in the programme and thus secure their support and guidance. The committees have apparently lived up to the expectation and have been doing extremely well to steer ahead the ultra poor programme over the last few years.

|

| Rangpur's Mehra in her nursery. Last year she made a profit of Tk 22,000 from selling plants. |

The villages where BRAC took this innovative programme are witness to this remarkable impression the committee has been making. The local influential people who are members of the committee were coming forward to stand by the poorest families of their respective villages. With the village elites' active participation, the struggle of the community's most wretched and distressed members for a better life suddenly became the responsibility of the entire community.

It is this aspect of nurturing a community feeling, developing and nurturing a new social link between the extreme socio-economic classes, i.e. between the ultra poor and the influential members of the village that makes the CFPR: TUP programme such a success. It is also what sets apart this programme from many other conventional poverty alleviation programmes. The programme is one that can act as a model to be replicated in other areas to make significant changes in the condition of the poor in the society.

It is not that the affluent villagers have never helped the poor before creation of the committee. It was mainly based on the altruism of the affluent class or personal relationships like when the poor woman working as a housemaid at a wealthy cultivator's house would receive help from her employer. Now, GDBC as a formal, institutionalised group is not only in a better position and far more competent to assist the poor, but also to act as advocates on behalf of all TUP members. "I used to give charity in a personal capacity, for example during a death or a marriage and usually to those I knew, now after being in the committee, unknown people also come to me and we all together try to help them," points out Wahed Ali, a GDBC member and an affluent cultivator in Rangpur's Shekhteri village. It is this shift from "I" to "We", from individual effort to collective effort that has been the hallmark of this notion of involving the village elites in the programme.

|

| Gopalganj's Nuru with her cows and goats that she has bought with her savings from raising poultry. A victim of dowry that finally ended in a divorce, Nuru wants to forget those bitter days. |

But how these village elites came to extend their helping hands? BRAC in the initial stages of the programme had arranged meetings with the programme participants and the village elites. "In those regular social interactions, we came to understand the kind of problems the poor women encounter in their daily lives, and how easily those problems could be overcome if we all lend our hands," Dr Azizur Rahman, a GDBC member of Shekteri area under Rangpur district, explains how the village elites got involved in the programme. "It's not that we did not have any idea about their problems, but we were certainly never made so much actively aware either. And it happened due to our continuous encounters that really helped us not only to understand but feel their problems," he elaborates. Then of course there were dramas arranged by Brac where real life stories were staged out, which also helped to bridge the gap between the ultra poor and the village elites better, Abdul Latif, TUP Supervisor, Jalkar, Rangpur, adds.

The GDBC plays an effective mediator between the ultra poor and the local government bodies. When Rangpur's Aliza went to the Gangachar Union Council office for Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) cards, {VGD cards entitle poor women to monthly wheat rations from the government and the World Food Programme (WFP)}, she failed to secure one. "They did not even listen to me properly," Aliza says in a complaining tone. But Dr Azizur Rahman and Imdad Ali Master, a teacher of Moinakutir High School, both GDBC members, went to the union council office and Aliza was readily awarded one. This type of mediation has also secured the quick response from the local livestock department as well as agriculture extension office. Since a good number of TUP members rear cows, goats and have poultry they are in frequent need of them. "Towards the beginning their assistance was hard to come by, but once we approached these offices in a body they started to respond," Azizur Rahman, explains.

Deepak Ranjan Roy, an official of Rangpur Sadar Livestock Department, says, " We try to pay extra attention to these poor rural women. Sometimes doctors tend to prescribe medicine without properly examining the sick animals, resulting in further deterioration of their condition and even deaths. But when a TUP member approaches us we always try to make sure that their animals are properly treated." Sufia, who has now four cows, two of which now give milk and her income from selling milk goes over Tk 40 a day, corroborates, " We know Rahman Bhai's home and even if we go to him at night he does not mind." Sufia is talking about Abdur Rahman, an official in Gangachara Upazila Livestock Department, Rahman gives his opinion on his ready response: " Yes, sometimes they do come at odd hours and very often beyond office hours, but I try to help them out. What is a bit of trouble for me, losing a couple of hours' sleep at most, can mean a huge service to them. And it feels good when you can come to someone's service."

Brac has given special cards to the TUP members that help the officials in these local government bodies to recognise them.

The Committee also played a crucial role in the initial stages of the programme. "When we told the villagers that we would give them land, cows, goats etc absolutely free many were suspicious. They thought we had some sort of ill motive, like 'we want to make them Christians' etc. The GDBC then came to our rescue. They are educated, now about Brac and they perfectly understood what we were trying to do. So we cleared away all their misgivings. We, BRAC people are outsiders, but these people (GDBC members) are local, well-known and our targeted people could easily rely on them," elaborates Abdul Latif. The Committee also played a crucial role in the initial stages of the programme. "When we told the villagers that we would give them land, cows, goats etc absolutely free many were suspicious. They thought we had some sort of ill motive, like 'we want to make them Christians' etc. The GDBC then came to our rescue. They are educated, now about Brac and they perfectly understood what we were trying to do. So we cleared away all their misgivings. We, BRAC people are outsiders, but these people (GDBC members) are local, well-known and our targeted people could easily rely on them," elaborates Abdul Latif.

GDBC assistance comes in different ways, sometimes in the form of financial help, but more often it is simply their expressed involvement with the poor that makes the whole difference.

Khadiza Begum was shattered when her cow that Brac gave her and which was her sole source of income got stolen one night. The GDBC of Belpukur village of Nilphamari where Khadiza lived, called a meeting and decided to donate one third of the money from the sale of hide of animals sacrificed on the Eid-ul-Adha. Tk 2,200 was collected and Brac contributed another 1000. A new cow was bought for Khadiza.

A mother of four children, forty--plus Mehra of Rangpur's Bahadur Singh village was suffering from goitre for years. She thought she would have to live with it for the rest of her life. Last year Murshidi, a young man of the same village and a GDBC member, admitted her into Rangpur Medical College hospital. After four days in the hospital Mehra came out cured and happy. Murshidi himself donated Tk 500 and collected another Tk 1,600 from some of the well-off people of the village and the rest Tk 5,000 needed for the operation was contributed by Brac.

|

| Brac school in Rangpur's Bahadur Singh village. The young learners are provided with all the reading materials and they don't have to pay any tuition fees either |

Rashida, six months after being included in Brac's TUP programme, with her two daughters was dreaming of a better and more prosperous life. Her dream fell apart when an accidental fire burnt her house and all the belongings to ashes. A group of local influential people accompanied Rashida to every house of the village; some donated money, some donated home--making materials and some gave labour. Within four days Rashida had a new home.

The assistance of GDBC is not limited to financial aid. In Rangpur's Shekhteri village, a local youth used to tease Shamsunnahar's 14-year- old daughter Farida on her way to school. Shamsunnahar complained to the boy's parents but nothing happened. "Then I went to Imdad Sir and told him everything. He immediately visited the boy's house and strongly reprimanded the boy and his parents. The family then apologised to me and never did the boy dare to disturb my daughter again," Shamsunnahar reports.

"I want to be a doctor," says Afrin, the girl of Class-III who stood first in her class. Afrin is sitting with another 30 of her classmates in the 12 by 25 feet tin-built Brac school in Rangpur's Bahadur Singh village. The students, dressed in blue, have sat forming a U shape on large pieces of sacks laid out on the earthen floor in a one-roomed school. But in this humble setting extensive dreams are being nurtured. Md Arif, the youngest of four brothers and sisters and the first child to come to a school, says he will become a businessman, and will earn a lot of money to fulfil his dreams, one of which is owning a brick-built house. These dreams are what Brac has initiated through its TUP programme. What is more, Brac has shown by example that small contributions from the affluent members of the community can change the face of the society. It has proved that the distance between a bleak present and a bright future is not necessarily so huge.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |