|

International

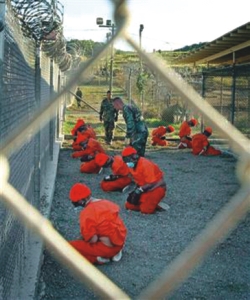

From Bagram to Abu Ghraib

Emily Bazelon

(Continued from last week)

A few weeks After the fall of the Taliban, in January 2002, a State Department memo described Bagram as "a temporary 'collection centre' where some detainees stop over enroute to their permanent location," typically Guantanamo. Over the following months, however, Bagram became much more than thatin part because troops in the field kept bringing in detainees who were not deemed valuable enough to send on to Guantanamo but were nonetheless kept at the base for months at a time. Many of them were local men arrested during U.S. raids on villages, according to Ahmad Fahim Hakim, deputy chair of the Afghan human rights commission. The problem, Hakim says, has been that the U.S. military frequently responds to tips from competing tribal factions, but isn't in a position to assess whether those claims are credible, or simply attempts to settle scores. "The Americans get a report that a village belongs to Al Qaeda," he explains. "When we go to check, we find nothing. The commission is very keen to share information about our cross-checking of these local accusations. But the coalition forces do not consult with us or with any other Afghan authority." A few weeks After the fall of the Taliban, in January 2002, a State Department memo described Bagram as "a temporary 'collection centre' where some detainees stop over enroute to their permanent location," typically Guantanamo. Over the following months, however, Bagram became much more than thatin part because troops in the field kept bringing in detainees who were not deemed valuable enough to send on to Guantanamo but were nonetheless kept at the base for months at a time. Many of them were local men arrested during U.S. raids on villages, according to Ahmad Fahim Hakim, deputy chair of the Afghan human rights commission. The problem, Hakim says, has been that the U.S. military frequently responds to tips from competing tribal factions, but isn't in a position to assess whether those claims are credible, or simply attempts to settle scores. "The Americans get a report that a village belongs to Al Qaeda," he explains. "When we go to check, we find nothing. The commission is very keen to share information about our cross-checking of these local accusations. But the coalition forces do not consult with us or with any other Afghan authority."

In May 2002, a few weeks before Hussain Mustafa was flown to Bagram, a 30-year-old Connecticut reservist was posted to the base as a senior interrogator. He and his team had come from a camp in the Afghan city of Kandahar, where they'd been conducting interrogations according to the 16 methods taught in their training standard questioning techniques, from "good cop/bad cop" to "we know all"and become frustrated by their failure to collect abundant useful information.

In Bagram, the interrogation team's number was cut from the 25 they'd had at Kandahar to 7. The team had about 200 prisoners to question and was processing between 35 and 40 a day. The reservist, together with Los Angeles Times reporter Greg Miller, later wrote a book about his experience, The Interrogators; the Army required that he use a pseudonym in writing the book and talking to reporters.

Chris Mackey, as the reservist is known, had been taught that harsh interrogation techniques yielded poor information because they prompted detainees to lie. Still, he recalls, "the more aggressive we werethough we never became physically violentthe more reliable the information was." His team realized that they often got their best information in the last half-hour of a 10-hour session, and they concluded that fatigue was their best available weapon. "We decided by committee that we couldn't get away with sleep deprivation under the Geneva Convention," Mackey says. "So we came up with this technique we called 'monstering.' We said that if you put one interrogator in with one prisoner and scrupulously gave them the same water and food and bathroom breaks, the interrogation could go on as long as the interrogator could stand it. Of course, we were hoping that the interrogator would be fully rested, whereas the prisoner would have just come off the battlefield."

Monstering wasn't in the Army manual, and before he came to Bagram, Mackey wouldn't have imagined improvising techniques that deviated from his training. But in Afghanistan, he increasingly felt compelled to produce intelligence that might help his fellow soldiers. "When I arrived, I would never have countenanced monstering," he told me. "But we saw how little success we were having against a determined enemy. So we went to what we thought was the absolute edge." Monstering wasn't in the Army manual, and before he came to Bagram, Mackey wouldn't have imagined improvising techniques that deviated from his training. But in Afghanistan, he increasingly felt compelled to produce intelligence that might help his fellow soldiers. "When I arrived, I would never have countenanced monstering," he told me. "But we saw how little success we were having against a determined enemy. So we went to what we thought was the absolute edge."

The Bush administration had decided at the beginning of the conflict that the Geneva Conventions did not apply to the Afghan detainees. But Mackey's commander never told him of that decision, and Mackey worried that he could be disciplined for breaking the rules. "As part of your training as an interrogator, it's hardwired into your system that a violation of the Geneva Convention will bring swift justice down on you," he says. At one point, Mackey remembers, a military police official at Bagram suggested that the interrogators use dogs to scare the detainees. "He was a reservist from Michigan, where there's a big Arab population, and he said that Arabs are terrified of dogs," Mackey says. "I remember sitting in a hot pizza oven of an office, arguing with everyone, trying to figure out how we could do this. But we couldn't - not out of any love for the enemy. We just thought we would get into trouble."

Asked about Mustafa's story of abuse - which would have taken place while his team was based at Bagram - Mackey says the culprits couldn't have been members of his unit, the only one formally questioning prisoners at the base (though he says he can't be sure whether the CIA had interrogators there). Former detainees, he points out, have "everything to gain for their cause by lying or exaggerating wildly." But, he adds, "10 months ago I would have told you, categorically, there was no way that this sort of thing could have happened. Now…the criminal abuses in Iraq - and the murders in Bagram - have robbed me of the comfort and uniformity of blanket denials."

IN AUGUST 2002, Mackey and his team turned over the detention unit in Bagram to the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion from Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The new head of the interrogation unit was Captain Carolyn Wood, a 34-year-old officer and 10-year Army veteran. Wood rewrote the interrogation policy set by Mackey's group, adding to it nine techniques not approved by military doctrine or included in Army field manuals. Her expanded list included "the use of dogs, stress positions, sleep management, [and] sensory deprivation," according to an internal Pentagon investigation known as the Fay-Jones report; the report noted that other techniques, such as "removal of clothing and the use of detainee's phobias," were also used at Bagram.

In December 2002, four months after Wood and the 519th took over at Bagram, two detainees died in custody at the base. One was Mullah Habibullah, a 30-year-old man from the southern province of Oruzgan; the other was a 22-year-old taxi driver named Dilawar (many Afghans use only one name), who was married and had a 2-year-old daughter. The men had been hung by their arms from the ceiling and beaten so severely that, according to a report by Army investigators later leaked to the Baltimore Sun, their legs would have needed to be amputated had they lived. The Army's Criminal Investigation command launched an inquiry, but few people outside Afghanistan took notice.

Then in March 2003, New York Times reporter Carlotta Gall tracked down Dilawar's brother in his home village. The man took from his pocket Dilawar's death certificate, which he'd been unable to understand because it was in English. Gall read the document and discovered that the Army pathologist who signed the certificate had checked "homicide" as the cause of death. The Times buried Gall's story on page A14; few other outlets picked it up. It wasn't until May 2004, more than a year later, that the Army released its report on the deaths. In it, investigators implicated a total of 28 military personnel in crimes including negligent homicide, maiming, and dereliction of duty. To date, however, only one person has been chargedSergeant James Boland, a reserve military police soldier, who is accused of denying medical care to Dilawar and watching a lower-ranking soldier beat Habibullah. "It is left up to the various commanders whether to bring legal action" against any of the other 27, says Army spokeswoman Lt. Col. Pamela Hart. So far they have not.

By the summer of 2003, it was the 519th's turn to leave Bagram. Despite Gall's report and the ongoing criminal investigation, they were redeployed to run another prison Abu Ghraib. There, Wood proceeded to implement new interrogation rules that, as a Pentagon report later noted, were "remarkably similar" to those she had developed at Bagram. In September 2003, the Army probed tips from other military police officers that members of the 519th had beaten prisoners at Abu Ghraib, but the investigators found the allegations unsubstantiated. Members of the 519th have not been directly implicated in the photographed abuses that set off the scandal.

Wood herself testified last summer at a military hearing in the case of Lynndie England, one of the soldiers prosecuted for the abuses at Abu Ghraib. Wood said she was "outraged" by the photos she had seen. Chris Mackey had trained with Wood before she got her command at Bagram. He says that while he was "gravely disappointed" when he found out about her changes to the interrogation rules, he understands what might have been going on. "After she took over, the stakes got very high," he says. "We went from losing three or four soldiers a month to scores of them. She must have been under a tremendous amount of pressure."

Mackey also says he couldn't imagine that Wood's superiors didn't know what she was doing. "I don't think it was sinister and programmatic," Mackey says of the military's handling of detainees in Afghanistan and Iraq. "But there was horrible incompetence at the leadership and oversight level. People were aware of what we were doing because we were open. [The prison] was practically a Disney ride, with lots of higher-ups and officials coming through. But the common response we got was, Aren't you kind of babying them?"

This article was first published in motherjones.com (continues next week)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2006 |

| |