|

Perspective

Our Inclusive National Past

Islam, West Bengal, and Pakistan

Rubaiyat Hossain Recently I have been fortunate enough to be exposed to the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-1984). As I was overwhelmed by the richness of Urdu poetic verses and the intense spiritual emotions conveyed in them, I could not help but feel a pang of discontent. This feeling of discontent rang a familiar bell. I have felt similarly last year when I visited Kolkata and witnessed the billboards in new market area holding quotes from Rabindranath Tagore.

In Bangladesh today, we are so busy and confused looking for our national identity that putting up Rabindranath Tagore's quotes on billboards in the city would call for political controversy. Similarly, studying Urdu language and literature would also stand opposed to our sense of nationalism. But by creating a cultural break with West Bengal and Pakistan, do we not shut ourselves out from claiming the beautiful literary and cultural legacy we have been historically a part of?

The fact that today we distance ourselves culturally from West Bengal and Pakistan and in many cases from Islam is precisely what gives rise to the confusion over national identity and eventually manifests in an Islamic militant movement. To be a sovereign Bangladesh does not mean that we have to distance ourselves from our historical past, rather, it means being inclusive of all that we are and all that we have been, which includes our past as a part of the larger South Asian landmass. If we take a look at our history then it becomes apparent that historically we have been at a disadvantage. We have been three countries in the past century and that is not certainly an easy thing to come in terms with.

Pakistan was established on the basis of claiming a sovereign place for the Muslims in South Asia. It promised them fair representation, education opportunities, job opportunities, and finally the freedom to practice Islam the way they wanted to. But Pakistan failed to remain a united state. This failure is a historic juncture looking at which one can understand the pathos of South Asian Islam, and what Islam has come to be in contemporary time. Religion has always been used by the British as a tactic to separate the polity and create internal communal violence. As the British directly took power from the hands of the Muslims, they diplomatically engaged in a process of tainting Islam in a negative light and depicting the Mughals as despotic oriental kings. The darkness that has been imposed on India was attributed to the Mughal empire. The politics of the British Raj successfully gave birth to a problematic partition. After partition Pakistan had to affirm its national identity and the simplest way to do it became 'not being India.' Urdu as a language and Islam as a religion were taken as the exclusive stamp of Pakistan. Pakistan was established on the basis of claiming a sovereign place for the Muslims in South Asia. It promised them fair representation, education opportunities, job opportunities, and finally the freedom to practice Islam the way they wanted to. But Pakistan failed to remain a united state. This failure is a historic juncture looking at which one can understand the pathos of South Asian Islam, and what Islam has come to be in contemporary time. Religion has always been used by the British as a tactic to separate the polity and create internal communal violence. As the British directly took power from the hands of the Muslims, they diplomatically engaged in a process of tainting Islam in a negative light and depicting the Mughals as despotic oriental kings. The darkness that has been imposed on India was attributed to the Mughal empire. The politics of the British Raj successfully gave birth to a problematic partition. After partition Pakistan had to affirm its national identity and the simplest way to do it became 'not being India.' Urdu as a language and Islam as a religion were taken as the exclusive stamp of Pakistan.

Thus, the problem arose. Which Islam? Arab Islam or Perso-Turk Islam? Pakistani Islam or Bengali Islam? Unfortunately, the answers have not been sought yet. However, the answers may lie in understanding South Asian Islam as inherently distinct from Islam in the Middle East or even Central Asia. Islam in South Asia is very much a product of centuries of eclectic exchange between the Hindu, Buddhist and Sufi Islamic philosophies, cultures, and rituals. The sense of Islam in Bengal is a part of this very tradition.

When we became sovereign Bangladesh the simplest way to be was to be 'not Pakistan.' The question arises, if we are not West Bengal and we are indeed not Pakistan (both landmasses we have been politically been a part of) then who are we? What are our cultural legacies? Who are our intellectual forerunners? We have our folk culture, but where do we trace our classical roots to?

We originally formed our country on a secular platform. We were Muslims, but we were Bangalis too. However, the question of whether we are Bangali before and Muslim afterwards or vice versa has not been answered yet, though Bangali Muslims have asked this question since the beginning of 1900. Our secularism did not give away to the fact that most Bangalis are devout Muslims, neither do I suggest that it should have. What I intend to point to is the state identity as a secular entity and our personal-cultural-spiritual beings as deeply religious gave rise to yet another problem, and that is of our treatment of Islam.

|

Faiz Ahmed Faiz |

We have misinterpreted Islam and given it into the hands of the uneducated, poverty stricken, and marginalised mullas who now are using it to their own political ends. Every Muslim Bangali child goes through a period of taking Arabic lessons in order to read the Qura'n. However, these lessons are hardly effective because the Arabic teachers bring with them fear and ignorance. We never read what is actually in the Qur'an. We never learn Arabic as a language so we can read the Qur'an and make sense of it for ourselves. We do not study the history of Islam in South Asia. As we distance ourselves from Pakistan once again we distance ourselves from the history of Islam in South Asia. The Islam that exists in Bangladesh has been brought by the Sufis from Persia in the 12th century whose philosophies have brewed in the soil of Pakistan. It is this particular brand of Islam that constitutes our spiritual entities, and since we have neglected to study it, we are suffering from a collective amnesia about our past and using Islam for its face value.

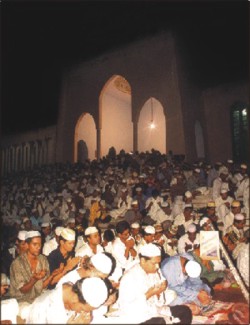

Being a ritualistic Muslim and praying five times and day, fasting during the month of Ramadan, and paying zakat is apparently not enough to understand how we evolved into the Muslims that we are today. A deep collective understanding of the cultural and historical progression of Islam in this region is an indispensable element in understanding who we are as a people today.

Even though we have been at a historical disadvantage of going through three partitions we are also lucky enough to be the descendents of one of most beautiful cultures history ever producedthe Islamic mystical tradition of Sufism. We are also the descendents of the most animated intellectual movements of colonial Bengal led by people like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Swami Vivekanando, Kesob Sen, Rabindranath Tagore, and so on.

By neglecting to take into account our intellectual and spiritual past we have created the vacuum that we feel in Bangladesh in terms of defining a holistic national ideology. What are we as a people? What are our aspirations? Who are our forefathers? Where do we come from? What constitutes our cultural-political-intellectual history? What shapes and motivates our spiritual currents? As a young individual looking back at my national past, I feel at a loss. And the times of loss are the times when we turn to literature for refuge. Thus, I end with Faiz Ahmed's ghazal 'Du'a' or 'Prayer.' It reminds us once again, we are the descendents of the mystical Islamic past which carries the symbolism of the moth burning itself in the flame, the very Sufi idea of annihilation or fana in the love of the Lord,

A'iye hath utha'en ham bhi,

Ham jinhen rasm-e-du'a yad nahin,

Ham jinhen soz-e-mohabbat ke siwa

Ko'i but, ko'I khuda yad nahin

A'iye arz guzaren ke nigar-e-hasti

Zahr-e-imroz men shirini-e-farda bhar-de;

Vo jinhen tab-e-giranbari-e-aiyam nahin

Unki palkon pe shab o roz ko halka kar-de

Jin-ki ankhon ko rukh-e-subh ka yara bhi nahin

Unki raton men ko'I sham' munavvar kar-de

Come, let us also lift our hands,

We who do not remember the custom of prayer,

We who, except for the burning fire of love,

Do no remember any idol, any God.

Come, let us present a petition that Life, our beloved,

Will pour tomorrow's sweetness into today's poison;

That for those who have not strength for the burden of the days,

May it make night and day weigh light on their eyelashes;

For those whose eyes have not strength for seeing the face of dawn,

May it light some candle in their nights.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2006

|