|

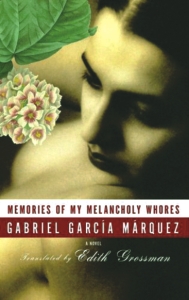

Literature

Sleeping Beauty

J. M. Coetzee

(Continued from last week)

I kissed her all over her body until I was breathless.... As I kissed her the heat of her body increased, and it exhaled a wild, untamed fragrance. She responded with new vibrations along every inch of her skin, and on each one I found a distinctive heat, a unique taste, a different moan…

Then misfortune strikes. One of the clients in the brothel is stabbed, the police pay a visit, scandal threatens, and Delgadina has to be spirited away. Though her lover scours the city for her, she cannot be found. When at last she reemerges in the brothel, she seems years older and has lost her look of innocence. He flies into a jealous rage and storms off.

His ninety-first birthday comes and goes. He makes peace with Rosa. The two agree they will jointly bequeath their worldly goods to the girl, who, Rosa claims, has in the meantime fallen head over heels in love with him. Joy in his heart, the sprightly swain looks forward to "at last, real life."

The confessions of this reborn soul may indeed have been penned, as he says, to ease his conscience, but the message they preach is by no means that we should abjure fleshly desires. The god whom he has ignored all his life is indeed the god by whose grace the wicked are saved, but he is at the same time a god of love, one who can send an old sinner out in quest for "wild love" (amor loco, literally "crazy love") with a virgin-"my desire that day was so urgent it seemed like a message from God"-then breathe awe and terror into his heart when he first lays eyes on his prey. Through his divine agency the old man is turned in no time at all from a frequenter of whores into a virgin-worshiper venerating the girl's dormant body much as a simple believer might venerate a statue or icon, tending it, bringing it flowers, laying tribute before it, singing to it, praying before it.

There is always something unmotivated about conversion experiences: it is of their essence that the sinner should be so blinded by lust or greed or pride that the psychic logic leading to the turning point in his life becomes visible to him only in retrospect, when his eyes have been opened. So there is a degree of inbuilt incompatibility between the conversion narrative and the modern novel, as perfected in the eighteenth century, with its emphasis on character rather than on soul and its brief to show step by step, without wild leaps and supernatural interventions, how the one who used to be called the hero or heroine but is now more appropriately called the central character travels his or her road from beginning to end. There is always something unmotivated about conversion experiences: it is of their essence that the sinner should be so blinded by lust or greed or pride that the psychic logic leading to the turning point in his life becomes visible to him only in retrospect, when his eyes have been opened. So there is a degree of inbuilt incompatibility between the conversion narrative and the modern novel, as perfected in the eighteenth century, with its emphasis on character rather than on soul and its brief to show step by step, without wild leaps and supernatural interventions, how the one who used to be called the hero or heroine but is now more appropriately called the central character travels his or her road from beginning to end.

Despite having the tag "magic realist" attached to him, García Márquez works very much in the tradition of psychological realism, with its premise that the workings of the individual psyche have a logic that is capable of being tracked. He himself has remarked that his so-called magic realism is simply a matter of telling hard-to-believe stories with a straight face, a trick he learned from his grandmother in Cartagena; furthermore, what outsiders find hard to believe in his stories is often commonplace Latin American reality. Whether we find this plea disingenuous or not, the fact is that the mixing of the fantastical and the real-or, to be more precise, the elision of the either-or holding "fantasy" and "reality" apart-that caused such a stir when One Hundred Years of Solitude came out in 1967 has become commonplace in the novel well beyond the borders of Latin America.

Is the cat in Memories of My Melancholy Whores just a cat or is it a visitor from the underworld? Does Delgadina come to her lover's aid on the night of the storm, or does he, under the spell of love, merely imagine her visit? Is this sleeping beauty just a working-class girl earning a few pesos on the side, or is she a creature from another realm where princesses dance all night and fairy helpers perform superhuman labours and maidens are put to sleep by enchantresses? To demand unequivocal answers to questions like these is to mistake the nature of the storyteller's art. Roman Jakobson liked to remind us of the formula used by traditional storytellers in Majorca as a preamble to their performances: It was and it was not so.

What is harder to accept for modern readers of a secular bent, since it has no apparent psychological basis, is that the mere spectacle of a naked girl can cause a spiritual somersault in a depraved old man. The old man's ripeness for conversion may make better psychological sense if we take it that he has an existence stretching back beyond the beginning of his memoir, into the body of García Márquez's earlier fiction, and specifically into Love in the Time of Cholera.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2006 |