|

Obituary

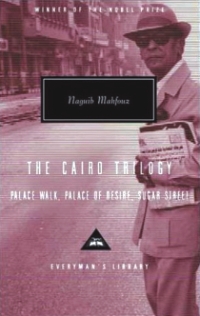

Mahfouz and his Literary “Diwans” Mahfouz and his Literary “Diwans”

Penny Spiller

It was a tradition that began decades ago, when he and his fellow writers and poets would gather in one of the city's many coffee shops, restaurants and hotels to mull over the issues of the day. In later years, these gatherings or "diwans" would attract a new crowd - thinkers from a broad spectrum of professions who kept the ageing writer in touch with the changing world.

They would also become an opportunity for fans to spend some time in the company of the only Arabic writer to have been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, which he won in 1988. Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif, who knew Mahfouz well, said the meetings allowed people to pay "a kind of homage" to "the grand old man of Egyptian literature".

The [gatherings] were a way of keeping his spirits up after the stabbing, and it worked - it did have the effect of keeping him in touch with the world. "People held him in great affection. He was a very big deal. People could be in his presence for a bit," she said. He had lived long enough to see his legacy come into effect. "There is nobody writing in Arabic today that has not been influenced by him," she said.

But old age and deteriorating hearing and eyesight limited his ability to contribute to the gatherings in later years.

He often had a friend sitting next to him who would shout loudly in his ear about what was going on, which made the meetings surreal at times. Khalid Kishtainy, an Iraqi journalist and writer based in London who has attended several such gatherings, was asked at one to read out his latest published work.

"I sat next to him and tried to read, but he couldn't hear me - I think he found my Iraqi accent difficult, but also I didn't shout loud enough," he explained. "In the end, one of his prompters said he would read it out. But Mahfouz showed great appreciation of my work, and laughed at all the funny bits." Raymond Stock, Mahfouz's American biographer and friend of 14 years, said the writer would often go into what he called his "screen-saver mode". "I sat next to him and tried to read, but he couldn't hear me - I think he found my Iraqi accent difficult, but also I didn't shout loud enough," he explained. "In the end, one of his prompters said he would read it out. But Mahfouz showed great appreciation of my work, and laughed at all the funny bits." Raymond Stock, Mahfouz's American biographer and friend of 14 years, said the writer would often go into what he called his "screen-saver mode".

"He would seem to be asleep, but he was very much aware of what was going on," he said. "On one occasion, a mosquito landed on his forehead and a friend raised his hand to swat it away. Naguib looked up and said: 'What do you want to hit me for?'" Naim Sabry, an Egyptian poet and novelist and another long-time friend, says it was his nature to say little. "He was a very good listener. He concentrated," Sabry said.

The "diwans" were the brainchild of renowned Egyptian psychologist and long-time friend of Mahfouz, Dr Yehia el-Rakkhawi. They started after Mahfouz was stabbed in 1994 by an Islamist extremist who had been inspired by a fatwa issued over the writer's portrayal of God in one of his novels decades earlier.

Mahfouz spent several weeks in hospital and suffered damaged nerves that limited his ability to write. Mahfouz will be remembered as a novelist first, says Ahdaf Soueif The gatherings "were a way of keeping his spirits up after the stabbing. And it worked. It did have the effect of keeping him in touch with the world," Stock said.

Informal affairs, the "diwans" were attended by a small group of regulars as well as journalists, doctors and engineers among others. They were held at a different location each night - most often at one of the hotels in downtown Cairo - and each one had a slightly different political emphasis. Informal affairs, the "diwans" were attended by a small group of regulars as well as journalists, doctors and engineers among others. They were held at a different location each night - most often at one of the hotels in downtown Cairo - and each one had a slightly different political emphasis.

"The more pro-Western liberals tended to come on Sundays, while those with more opposing views would attend on Tuesdays and Fridays. Wednesdays were more mixed," Mr Stock said. Thursdays were invitation-only, for his closest group of friends known as the Harafish ("riff-raff"), while on Saturdays he would receive people at home. Sabry says there is talk of keeping the gatherings going in memory of their friend. But he thinks it is unlikely they will carry on for very long.

"Naguib was the core of the gatherings and it will be strange without him there," he said. Mahfouz continued to write by dictation until he fell ill, adding to an output that included more than 30 novels and over 100 short stories, as well as numerous articles and film scripts.

He became famous for his vivid portrayals of life in his beloved city and Egypt's experience of colonialism and authoritarianism. He was considered a progressive thinker who was a strong advocate of moderation and religious tolerance, which often pitted him against conservatives in Egypt. Stock said he detected a shift in the writer's political views in the last few years over US foreign policy, particularly over the "war on terror". "He was very much against it. He had a simple view that if you remove the injustice, there will be no more trouble," he said.

"But he was wise. On one occasion, someone was attacking the idea of the US proposing democracy in the Middle East, and it was pointed out that Egypt had once had democracy, and people wanted it again. "'We agree about democracy,' Mahfouz said. 'Sometimes our interests are the same,'" Stock recalled. Ahdaf Soueif says it will be his literary, rather than his political legacy that will remain. "He was always a novelist before anything else."

This article was first published in Bbcnews.com

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2006 |