| Cover Story

Choking Voices of Freedom Choking Voices of Freedom

Free thought is fast becoming another casualty of rising religious extremism

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Last month, at a public meeting at Rajshahi University (RU), activists of Islami Chhatra Shibir, the student wing of Jamaat-e-Islami, threatened to cut up Hasan Azizul Haq, professor of philosophy at the university and eminent writer, and throw his body into the Bay of Bengal. Haq had spoken at a seminar on secularism, and his speech was misconstrued in some newspapers as being offensive to Islam. Labelling him an atheist and enemy of Islam, the Shibir activists declared the professor persona non grata at the university and demanded that steps be taken to remove him, otherwise the students of the university would throw him out. If he did not revoke his statements on secularism, his fate would be the same as those of Taslima Nasrin and Humayun Azad, they said.

Just the day before, reputed columnist, writer and professor of chemistry at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST) in Sylhet, Dr. Md. Zafar Iqbal, was threatened by activists belonging to the same group. Zafar Iqbal, along with a number of other faculty members, had protested the return to office of the vice-chancellor of the university. According to a news report in the daily Prothom Alo, they threatened to cut off his tongue.

“They’re fascists,” says Zafar Iqbal in an interview with SWM. “They deliberately try to stop anyone who says anything against them by threatening them.”

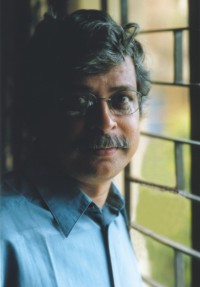

Prof. Dr. Md. Zafar Iqbal: There will be no compromise with fascists |

“Personally, I am not willing to give them that much importance,” he says. “The killers of 1971 were cowards. Similarly, these groups are nothing big, nothing great. I want to treat them as insignificant as they are. Others, however, should not take the matter lightly,” warns the professor. “Because they kill. Two professors of RU were killed. Nothing happened to the killers, they got away with it. With support from the government machinery, the man who killed one of them was even allowed to sit for his exams.”

Iqbal was surprised by the threats made to him only because they were made by students of his university. “Even though they were not from my department, they were students of my university and that surprised me, that they would behave this way with me.”

“But there will be no compromise,” says Iqbal. “Those who write know what they’re in for. Those who are afraid don’t write anything controversial to begin with. But for those who practise free speech, there’s no stopping them.”

“They are a very small group,” says Iqbal, referring to the perpetrators. “But they have protection of a section of the government, and they terrorise people. For example, these groups have stopped the holding of cultural programmes at certain educational institutions. But believers in democracy and free speech must come out and resist, they should go ahead and organise their programmes, no matter what the consequences may be.”

Such bravery may not seem very practical in a situation where threats are not merely intimidating but carried out with vehemence.

In February of this year, professor of geology and mining at RU, S. Taher Ahmed, was killed. His body was later found in a manhole behind his house. One of the men implicated in his murder, Mahbubul Alam Salehi, is a leader of the local Islami Chhatra Shibir. After the murder, Salehi led a procession on campus protesting the accusation. He also got special permission from the university vice-chancellor to sit for his exams. He has still not been apprehended.

In December 2004, economics professor of Rajshahi University Muhammad Yunus was stabbed to death. The killers, who have yet to be caught, are suspected to have links with Shibir.

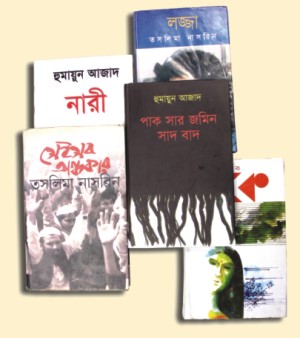

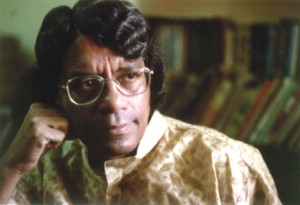

Earlier, in March of the same year prominent writer and professor of Bangla at Dhaka University (DU), Dr. Humayun Azad was attacked by religious fundamentalists, hacked almost to death. Weakened and traumatised by the attack, he later died in Germany, apparently of natural causes. In January of that year, following publication of Azad’s satirical novel Pak Sar Jamin Saad Baad in the Eid issue of a national daily, religious bigots had declared the professor a murtad (apostate) and held rallies demanding his arrest and trial for blasphemy. Earlier, his novel Nari had also been banned. Earlier, in March of the same year prominent writer and professor of Bangla at Dhaka University (DU), Dr. Humayun Azad was attacked by religious fundamentalists, hacked almost to death. Weakened and traumatised by the attack, he later died in Germany, apparently of natural causes. In January of that year, following publication of Azad’s satirical novel Pak Sar Jamin Saad Baad in the Eid issue of a national daily, religious bigots had declared the professor a murtad (apostate) and held rallies demanding his arrest and trial for blasphemy. Earlier, his novel Nari had also been banned.

After the publication and soaring popularity of her book Lajja in 1993, a fatwa was issued against feminist writer Taslima Nasrin for insulting Islam. With thousands of religious extremists protesting on the streets demanding her head, and with the government’s issued arrest warrant on blasphemy charges, Taslima Nasrin was forced to flee her homeland. Her other books including Amar Meyebela (1999), Utal Hawa (2002) and Ko (2003) have also been banned, the latter by the High Court.

In the early 1990s, DU professor Dr. Ahmed Sharif faced the wrath of religious fundamentalists who accused him of blasphemy and demanded his execution.

These are only the better known and remembered cases of attacks on freedom of speech. The list is much longer, with Nirmolendu Goon picked up by the military intelligence in 1975, and Shahrier Kabir, Muntasir Mamoon, Farhad Mazhar all jailed at different times for daring to speak out against the norm.

The culture of intolerance has become even more prominent in bomb attacks on cultural functions. Religious extremist groups, for example, were responsible for bomb attacks on cultural functions held by Udichi in Jessore (1999), Chhayanaut at Ramna Batomul (2001) as well as in cinema halls in Mymensingh. A spate of bomb blasts around the country over the last two years carried out by extremist groups targeting and killing, among others, judges and lawyers, have further demonstrated the surge in religious fundamentalism. Moreover, members of the religion-based groups have warned the nation that if those accused of the crimes (i.e., notorious Jama’atul Mujahideen Bangladesh -- JMB -- leaders like Shaikh Abdur Rahman and Bangla Bhai) are punished, for every one of their leaders who are hanged, 50 people will be killed.

Historically speaking, the situation is much worse today than it was three decades ago. With intolerance remaining constant, its acceptance seems to have grown. Each time, the champions of free speech have fallen while the perpetrators got away.

While this scenario is indeed intimidating, the only ray of hope is that there is a countertrend of increasingly open condemnation of religious extremism in the country's print media. The majority of newspapers have been consistent in exposing the threat of religious extremism in spite of the government's initial reluctance to do so.

Generally, whichever political party is in power, it decides to collaborate with the religious parties in the hope of winning more votes come election time. The tricky bit is that, seen carefully, it becomes obvious that the issue is not solely religion. It is more about political gain, and mostly about power. Disrespect towards and intolerance of other’s views and opinions or a different ideology has begun to take a terrifying toll on the, basically, secular-minded people of this country. Besides the loss of so many lives, the ultimate casualty of such fundamentalism has been freedom of speech and expression, individuality and diversity, plurality and democracy.

Barrister Tania Amir: Freedom of speech and expression are guaranteed absolutely by the Constitution of Bangladesh |

Article 39 (1) of the Constitution of Bangladesh guarantees freedom of thought and conscience. Section 2 of the same article also guarantees freedom of speech and expression, and freedom of the press. These are guaranteed subject to “reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interests of the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offense”.

Decency and morality, says Barrister Tania Amir, refers to obscenity, pornography, etc. “Other than that,” she says, “freedom of speech and expression are guaranteed absolutely by the Constitution.” In fact, it is those who break the “reasonable restrictions” who break the law, says Amir.

According to Section 503 of the Penal Code Act, 1860, any person who threatens another person with “injury to his person, reputation or property” causing them alarm and making them do or not do something to avoid execution of such threat commits “criminal intimidation”. Anyone who does this is punishable with up to two years’ imprisonment or a fine or both. If the threat is to cause death or grievous hurt (among other things), the term of imprisonment may extend to seven years. So, basically, anyone who threatens someone else is punishable by law.

Section 508 of the Penal Code Act, 1860, specifies even further, that a person who causes another person to do or not do something for fear of incurring “Divine displeasure” may be punished with a fine, up to a year’s imprisonment, or both.

“Though the word fatwa is not mentioned in the code,” says Barrister Tania Amir, “‘Divine displeasure’ refers to the same thing, i.e., the threat of incurring the wrath of God, or some such Supreme Being. According to the provisions in the Penal Code then, fatwas are illegal, and it is the fatwa-givers who have committed hate crimes,” she says. “By inciting violence, disrupting public order, and, as in the case of the Qadiyanis, by causing unlawful confinement, fatwa-givers have committed crimes punishable under the Penal Code.”

But no steps have been taken against the perpetrators because the government has turned a blind eye, says Amir. Thus the extremist groups continue to operate with impunity. “It is almost as if there is a tacit understanding between the government and the perpetrators, as if the former are telling the latter, ‘go ahead and unleash your reign of terror and hate crimes, the government will give you protection’. The government seems to be working hand in glove with the extremists.”

“Rule of law means the law must be enforced against anyone who breaks the law,” continues Amir. “But no police or RAB action was taken against such perpetrators, including, when Bangla Bhai first came to the limelight. He caused physical assault, injury, coercion, grievous bodily harm, yet the local police seemed to have been protecting him and his associates who purported to justify such crimes under some bizarre understanding of Islam.”

“The Constitution is the highest law in Bangladesh,” says Amir, “and it guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, speech, association, movement and sport.” She makes reference to the incident in which a number of young girls from mufassil towns were to participate in a girls’ swimming competition. But a fatwa was issued against them and the girls had to go back without taking part in the competition. “The girls were not committing a crime,” says Amir. “Their freedom to take part in the competition was guaranteed by the Constitution. Yet the government takes no action against the real offenders who instigate hate crimes by giving fatwas. They kowtow against such illegal and oppressive criminals instead of putting them behind bars.”

Religion-based politics is more about political, rather than spiritual, gain

Thus, in the ultimate logical conclusion, such omission by the government to take lawful action against these criminals is a grave constitutional breach, allowing a climate of impunity to these offenders, says Amir. “It could also be argued that the government, through this action or non-action, are aiding and abetting the principal offenders. The failure and omission of the government makes it an offender as well, for it is the positive duty of the government to take appropriate action under the Penal Code and prosecute them. Not doing so is grave constitutional negligence.” The government itself becomes liable for its tacit approval and systematic non-prosecution of such fatwa-givers who are trying to propagate a climate of fear, intimidation, dogma and fanaticism, says Amir.

The war on freedom of thought can be traced back to our own war of independence when, on December 14, a number of intellectuals were killed, leaving a long, dark vacuum that has yet to be filled.

"The intellectual killings in 1971 were a part of the genocide," says Prof Serajul Islam Choudhury, social activist and former professor of English at DU. "We thought all that had ended in 1971. Today, Bangladesh is a liberated country. Things like this happening here, now, is very unexpected."

What is even more alarming, says Choudhury, is that the threats being made to the intellectuals today are not just threats. “They actually materialise, as we saw happen in the case of Dr. Humayun Azad,” he says. “The university professors who have been threatened recently have been done so by the same group of people. This means that those forces are still active.”

Prof Serajul Islam Choudhury attributes the rise in extremism in Bangladesh to three main causes.

“The first is the role of madrasas,” he says. “In an already backward society, they are churning out more and more students. These students who are not educated in the mainstream system cannot find employment; they become frustrated and get involved in such activities. Madrasas are a breeding ground for such extremists.”

“The second factor is religion-based political parties in our country. They are not only political forces, but are now actually in power. They were politically rehabilitated by the Awami League when they were in power, and now they are in the government, with steps being taken, like the equivalence of madrasa education with mainstream education. This is a new and alarming phenomenon,” says the professor.

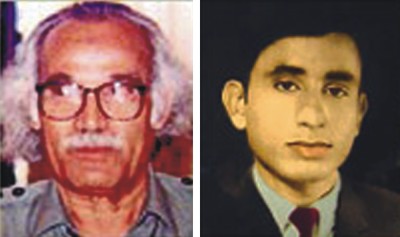

Prof. Muhammad Yunus and Prof. Dr. S. Taher Ahmed -- the two Rajshahi University teachers killed allegedly by activists of Islami Chhatra Shibir

“The third reason is that the perpetrators are not being caught,” says Choudhury. “Those who have been arrested have not disclosed their linkage, their source of funding, their patrons. From the Udichi and Mymensingh bomb blasts to the CPB and Ramna Batomul attacks, the perpetrators have not been exposed, key information not unearthed. There has been no trial and no punishment. And so the criminals believe they can continue to do these things with impunity.”

Investigations are weak, says Choudhury, as was demonstrated in the case of Jessore. “The police and judiciary seem unable or unwilling to handle it. The government is not acting. The issues are addressed in the media, but it is not enough to identify the symptoms only. The root causes must be exposed,” he stresses. “Unemployment, for example, is a big problem, which causes youth to become easily persuaded to commit such crimes.”

Though it may be difficult, there are ways to remedy the situation. According to Prof Serajul Islam

Choudhury, there should be no separate madrasa education system. “Neither should

Late Prof. Dr. Humayun Azad was attacked by religious fundamentalists at the Ekushey Book Fair in 2004 |

there be separate English medium education,” he points out. “These are also separate from the mainstream and are not having any healthy impact on society either. The education system should be integrated to include all three in one single, uniform system based on the mother language,” says Choudhury. “This may sound drastic at first, but it is on this basis that our nation was created.”

“Bangladesh was founded on the basic principle of secularism,” says Serajul Islam Choudhury. “Later, the Constitution was amended to make it an Islamic state. Secularism has to be restored. Any patriotic, well-meaning citizen will want this, for secularism is the first step towards democracy.”

Right now, however, religion-based politics seems to be far from over. Jamaat-e-Islami and Islami Oikyo Jote are already part of the ruling coalition and new parties are being formed, the latest being Ahle Hadith Andolon Bangladesh’s (Ahab) “Insaf”.

"It is with the tacit approval of a section of the government that such parties are being allowed to exist," says Choudhury.

Many, however, believe that if people vote these parties into power, then they have a right to exist. According to Serajul Islam Choudhury, however, the people only vote for religion-based parties because they do not have a choice. "Both our main political parties have used religion in their politics. If the religion-based parties stood alone in the elections, without the support of the two major parties, I believe they would fail miserably," he says.

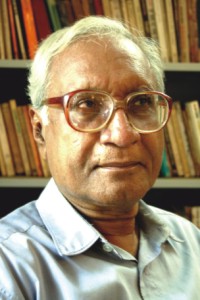

Prof. Serajul Islam Choudhury: Religious fundamentalism is a threat to democracy |

“These fundamentalists who are trying to intimidate people are not a threat only to intellectuals or individuals but to the very basic principle of democracy,” stresses Choudhury.

John Milton in Areopagitica argued for total intellectual freedom without any government control. He believed that everyone should be able to express themselves freely. The “true and sound” would survive while the “false and unsound” would be vanquished. But in a society brimming with intolerance and reluctance to respect any idea other than one’s own, where does one draw the line between freedom and responsibility? And who decides the degree to which people can assert their right to express their views and opinions?

“The people of Bangladesh are suo juris,” says Barrister Tania Amir. “They are fully capable of making up their minds on any book, literature, publication, media broadcast, etc. It is not up to the government to decide what the public should or should not have access to. The government is not authorised to decide or infringe or encroach upon the discretion of the citizens as suo juris to decide what they will see, hear or read. If the people don’t like a publication, they will reject it, but they have a right to know. The government or state has not been authorised to decide what information they will feed the citizenry or what they should not have.”

“All power belongs to the people,” says Amir, “who should not be treated as minors or wards of the government. It is not up to the government to decide what sort of literature, ideology or dogma the citizens should be exposed to.”

“Intimidation is always done by cowards who are incapable of engaging in any real debate,” she says. “This republic is a democracy, society pluralistic, a tapestry of different colours and ideas. Our strength lies within this colourful diversity. Any attempt to propagate only one view or preference of one colour or view over the other or restricting the dynamics of ideas and interplay of different ideas would be a travesty whereby human intellect would be reduced to a casting mould which would be parroting the same ideas over and over. That would be the end of all creativity, diversity and championing dogmatism, fanaticism and fascism.”

As John Stuart Mill said in On Liberty: "If all mankind minus one were of one opinion, and only one person was of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind. The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it robs the human race, posterity as well as the existing generation. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity to exchange error for truth; if wrong, they lose what is almost as great a benefit -- the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error."

Feminist writer Taslima Nasrin was forced to flee Bangladesh in the early 1990s after fundamentalists demanded her arrest and execution for insulting Islam. The physician-cum-writer has spent the past several years in exile in Sweden, the United States and India. Star Weekend Magazine (SWM) in an exclusive interview with Taslima Nasrin (TN), now in Kolkata, asks the writer whether she wants to come back home, and what sort of a country it is today for those who dare to speak their minds.

SWM: You have been in self-exile for over 10 years. Do you want to come back home?

Taslima Nasrin, author of controversial books like Lajja and Ka Taslima Nasrin, author of controversial books like Lajja and Ka |

TN: Of course, I want to go to back to my beloved country. But the Bangladesh government is not willing to allow me to return. I have been to numerous Bangladesh embassies in western countries in order to renew my passport, but no ambassador has agreed to renew my passport. They have closed the door on me, in other words, the very door of my own home. My right as a citizen of my country has been constantly violated by governmental authority, whether in Khaleda or in Hasina’s regime, it's always the same. They may differ in some respects, but their answer is always that I must be prevented from returning to Bangladesh. However, I am a legal citizen of Bangladesh, and they have no right to violate my right to live in my own country. They are acting as if they are the owner of the country, not the country's responsible leaders. Regretfully, and surprisingly, people are not protesting this government's hostile attitude towards me.

SWM: How big a threat do you think religious fundamentalists are to writers, intellectuals and to freedom of speech and expression in general? How seriously do you think this threat should be taken?

TN: Bangladesh commenced as a secular, democratic country. But successive military generals, who usurped power, gave up secularism and declared the country an Islamic state in order to make themselves popular among the masses. When, after more than a decade, democracy was finally restored, the elected leaders did not restore secularism as the guiding spirit of the country's Constitution. They, too, feel that, because religion is important to the masses, it is a useful tool for control. Even the opposition is hesitant to disturb the fundamentalists for fear of losing political support. In short, when almost all the political parties make political hay out of religious sentiments, there is no reason why that situation would not be favourable for the fundamentalists.

However, Bangladesh is not governed by religious clergy, not yet. Political power is not yet in the hands of any religious fundamentalist party, not yet. When the Mollahs issue a fatwa from time to time, it has no constitutional legitimacy or legal sanction. But seldom is any action taken against them. Doesn't this indicate a compromise with fundamentalism?

The problem of the fundamentalists is the belief that individuals do not count. Group loyalty over individual rights and personal achievements is a peculiar feature of fundamentalism. Fundamentalists believe in a particular way of life -- they put everybody in their particular straitjacket and dictate what an individual should eat, what an individual should wear, how an individual should live everyday life: everything is determined by fundamentalist authority. Fundamentalists do not believe in individualism, liberty of personal choice, or plurality of thought. Moreover, as they are believers in a particular faith, they believe in propagating only their own ideas (as autocrats generally do, also). They do not encourage or entertain free debate, they deny others the right to express their own views freely, and they cannot tolerate anything that they perceive as going against their ideology. They do not believe in an open society and, though they proclaim themselves a moral force, their language is that of hatred and violence. As true believers, they are out to "save the souls" of the people of their country by force of arms if necessary.

The fundamentalists are a major threat, not only to writers, intellectuals, and to freedom of speech and expression but also a tragic threat to the whole nation. Their aim is to make a theocratic state, one that is against democracy, human rights and women's rights. If the fundamentalists continue to go unopposed, they will destroy the country. For that reason, everybody has a patriotic duty to fight the fundamentalists before it is too late. Or is it already too late?

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2006 |

|