|

Photography

The Lens of Truth

Nader Rahman

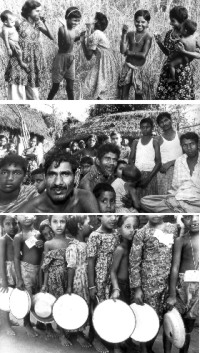

Most coffee table books are essentially fluff, hardbound, expensive, full of pictures with little or no text of importance. Mahmud's 20 Villages: Kurigram is an exception to that rule. The book is a photographic journey through Kurigram a district in northern Bangladesh. It takes one through the four rivers and numerous alluvial islands that appear and disappear almost at will. The lives of the people of Kurigram are depicted with raw honesty and artistry, not the most common combination.

The book designed by Masuma Pia of Matri is hardbound, slightly expensive and full of pictures but it really stands out because of its text. The Bangla writing has been edited by Ayaz Mahmood while the English translation has been expertly done by Fakhrul Alam and Faye Rodriguez. The writing mingles seamlessly with the pictures.

If one were to generalise the stories as those of hardship, it would be entirely wrong. They are in fact stories of real life, the simplicities and intricacies that define life in Kurigram.

Some themes are repeated throughout the book, and that is seemingly done to accentuate their importance.

Child marriages are repeated over and over again. The stories are hardly ever different, merely the names and faces are. The book is riddled with child brides and their plight, most of them are married off by the 4th grade and in one village the oldest unmarried girl was 12. Most of the girls have accepted their fate, and that is where the problem lies. This book and its pictures brings forward a shocking social norm of the villages, and Mahmud extracts truth from every picture. There comes a point in the book when one wonders what comes first the pictures or the text. The stories are heart wrenching and the pictures perfectly fill the lines between the text. While some people are the child brides, others seek to liberate them. The story of Farida Perveen's neighbour is one highlight through the deluge of early marriages. She dreams to liberate her neighbour who is routinely beaten by her in-laws; her ambition of being a policeman will probably never be realised but at least she has a conscience. Child marriages are repeated over and over again. The stories are hardly ever different, merely the names and faces are. The book is riddled with child brides and their plight, most of them are married off by the 4th grade and in one village the oldest unmarried girl was 12. Most of the girls have accepted their fate, and that is where the problem lies. This book and its pictures brings forward a shocking social norm of the villages, and Mahmud extracts truth from every picture. There comes a point in the book when one wonders what comes first the pictures or the text. The stories are heart wrenching and the pictures perfectly fill the lines between the text. While some people are the child brides, others seek to liberate them. The story of Farida Perveen's neighbour is one highlight through the deluge of early marriages. She dreams to liberate her neighbour who is routinely beaten by her in-laws; her ambition of being a policeman will probably never be realised but at least she has a conscience.

Another recurring theme is that of dreams. The fractured dreams of the inhabitants of Kurigram are portrayed exquisitely through the lens of Mahmud. The geography of the area defines and divides lives of the people who live there. During the monsoon the rivers put more than half of Kurigram underwater and when they eventually recede they leave behind rich alluvial soil. That soil is tilled by people who do not even own the land, they sharecrop with other people. His picture “A cart push” is Spartan but speaks volumes about the hardships of farming in the alluvial soil. Rahim, Badshah and Jabed are young children who work with their fathers pushing carts. They openly say that pushing the cart through loose soil is tough on them, it leaves them breathless in more ways than one. But dreams seem to be the only respite from real life in Kurigram, the children dream of not working, while the adults simply dream of living through it all. One can then say that this is a book of two halves, one portraying the realities of life the other seeking to leave them behind.

The book not only puts forward the plight of child brides and distant dreams, its pictures capture the emotions behind the toil of everyday life. The pictures and text behind “Cowboys” was an eye opener. The picture was simple enough, that of a boy lying on the grass cleaning his teeth with some grass. But the text really put that image into perspective when it said that cows were the ultimate form of money and investment in Kurigram. For the extremely poor to own a cow is a big deal and cowboys are employed to feed and protect the cows from harm. The harsh realities of life in northern Bangladesh have never been dealt with in such an artistic manner. The book not only puts forward the plight of child brides and distant dreams, its pictures capture the emotions behind the toil of everyday life. The pictures and text behind “Cowboys” was an eye opener. The picture was simple enough, that of a boy lying on the grass cleaning his teeth with some grass. But the text really put that image into perspective when it said that cows were the ultimate form of money and investment in Kurigram. For the extremely poor to own a cow is a big deal and cowboys are employed to feed and protect the cows from harm. The harsh realities of life in northern Bangladesh have never been dealt with in such an artistic manner.

Education or the lack of it also plays a vital role in the book. The story of Nur Islam best highlights that point. He says “ I don't go to school anymore I started class five but because my parents were poor and could not afford to buy the school dress for me, my teachers would be angry while my classmates would tease me. That is why I gave up school.” The picture that accompanies the text is that of Nur Islam himself, dried grass tied to his head acting as a cushion to help carry heavy objects, bare chested and utterly lost. Like him there are many others from the 20 villages who were forced to leave school. Their pictures capture the pain behind a struggle for life that starts too early. We are told that children are our future, but their lives depicted in Mahmud's book point to a generation of disenchanted youth.

The picture that Mahmud paints is that of extraordinary situations that come together to from life in Kurigram. Islands are created and destroyed over night, Tinhajarir Char is one of them. It was created roughly four years ago, but people have only inhabited the island fro the last one-year. The occupying picture is that of a religious school and it just goes to show how religion plays an integral part in their lives.

At the end of the day this is book with a conscience. Reality is forced into the readers face, and it comes from the most unusual place. Children show the reality behind their lives, and the reader cannot shy away from the truth. It shines through Mahmud's pictures.

Photos: 20 Villages, Kurigram by Mahmud

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2006 |