| Cover Story

Bangali Consciousness Abroad

Aasha Mehreen Amin, Hana Shams Ahmed and Elita Karim

The inherent resilience and adaptability of Bangalis no matter how unfamiliar and harsh the circumstances are, has taken them to the furthest corners of the world. The thirst for greater knowledge and the desire for a better life has led millions of Bangalis to leave their country of birth and go abroad, often making a foreign country their home. Yet no matter how assimilated the malleable Bangali is, no matter how attractive the adopted home and lifestyle is, there is always that hankering for the homeland. It is that irrepressible urge to establish one's ethnic identity in an alien environment that constantly prompts the expatriate Bangali to somehow stay connected through music, literature, traditions or merely by speaking in the mother tongue.

|

| No matter how attractive the adopted home is, there is always a yearning for the homeland |

Photo: Drishtipat |

Preserving 'Bangaliness' is perhaps most zealously done by older generation Bangalis who went abroad when they were adults, found suitable jobs, settled and ended up living out their whole lives in a foreign land. For these people their Bangaliness is given, says Azizul Jalil, a former World Bank official and freelance columnist who has lived in the US for most of his life. “The Bangla language, culture and its practice are a part of their identity, which they pass on to their children born in the US (for example),” says Jalil who has raised his children there. “Legends of the Battle of Palassy, Khudiram's hanging, Chittagong Armoury raid, various peasant movements, Subhas Bose and the Indian National Army, the language movement and the Bangladesh's war of independence are very much part of the older Bangladeshis' emotional and national ethos”, he says adding that “living in the US with the immediate family for many long years and even taking citizenship have not detached them from the natural and loving bonds with language and culture of their homeland.”

Jalil has four grandchildren-all born of foreign mothers, who appreciate Bangla music, dance and Bangladeshi clothes. “One of them a five year old, was so enchanted by Nrityanchal's dance performance at Dr. Yunus's Nobel Prize award ceremony in Oslo that we have to play the accompanying Rabindra Sangeet “Rangiya die jao go amay” repeatedly and have bought CDs of other Tagore's dance dramas,” exclaims Jalil.

Reading Bangla literature, watching Bangladeshi channels via satellite and being in touch with current affairs in Bangladesh through Bangla newspapers, many of which have online editions, is also a way that many Bangalis maintain the cultural connection. Bangla weeklies are a dime a dozen these days in the US and other countries with large Bangla-speaking populations. Thikana, Bangla Patrika, Parichay, Kagoj, Akhono Somoy, Janmabhumi, Deshbangla, for instance, come out of New York, Priyo Bangla from Atlanta and Bangla Barta (weekly) and Poroshi (monthly) from California...

For second generation Bangali immigrants, however, cultural identity is not always so simple. “Both my parents immigrated to the United States before the Liberation War and in the 1970s and 1980s there weren't many large Bangladeshi communities in the U.S. My mother immersed my South Asian cultural education in Hindi movies and songs and classical Indian dancing (Kathak) and instruments (sitar),” says 31-year-old Roksana Badruddoja, a sociologist and an Assistant Professor of the Women's Studies Program at the California State University, Fresno, who was born and brought up in the U.S. “As Bangladeshi networks began building, my mother tried to immerse me in learning to read and write Bangla and sing Rabindra sangeet, but I was uninterested and my mother left it at that. Today, while I still do not read and write Bangla, I am able to fluently speak the language and I am recently beginning to explore contemporary Bangla music composed by musicians like Fuad and Habib,” says Roksana who completed her Ph.D in Sociology from Rutgers, the State University of NJ, worked as a domestic violence advocate and crisis Counselor for immigrant South Asian women and is currently working on a book titled "Brown Souls: The Stories of Second-Generation South Asian-American Women."

|

| Bangali festivals like Pohela Baishakh gives expatriate Bangalis a chance to recreate their traditions |

Photo: Drishtipat |

Roksana says that it was very difficult to juggle between her 'South Asian / Bangladeshi' and 'American' identity as a child and adolescent. “First, before entering the house, I would take off my sneakers my outside shoes in the garage and slip into my indoor sandals before entering the home. Second, I would shed my western outfit, take a shower to cleanse myself off the day, and slip into a shalwar kameez. This purification act, which consisted of a simple procedure of shedding, cleansing, and changing, allowed me to cognitively switch from a world of 'American' friendship bracelets to one of 'South Asian' gold bangles. As an adult, I separate my 'South Asian' clothing from my 'American' clothing in my closet and my Hindi and Bangali-language music from my English and Spanish CDs. “My daughter's (three and a half years old) cultural upbringing is also invested in Bollywood and Bangladeshi or South Asian-style clothing. I simply do not carry enough knowledge to teach her about Bangladeshi culture in its true nature, and it does not seem natural to me to instil Bangladeshi culture in her, including the language. The notion of authenticity is a

Roksana found it very difficult to juggle between her 'South Asian' and 'American' identities as an adolescent |

critical question here and hence I leave it to my mother to teach Bangladeshi culture to her. What I am interested in instilling in my daughter, who is a third-generation American, is Bangaldeshi-American cultural values, which fosters a form of partial hybridity between 'Americanness' and 'South Asianness'.” When she was a child, Roksana's parents made it a point to take her and her sister to Bangladesh every year to spend time in the country. But since college she rarely comes to Bangladesh. Roksana says that while she is extremely attached to her Bangladeshi heritage and people from Bangladesh and she strongly identifies herself as a Bangladeshi-American, she feels little ties to the land. “It somehow feels foreign to me,” she says.

***

Shushma Sharmin, a 26-year-old writer has lived in New Jersey for more than 10 years and says that it is her interest in the arts that has helped her hold on to her Bangali cultural identity. “I have always been taught to appreciate and respect Bangali music which has that certain something that cannot be found in western music,” says Shushma, “Another thing I hold on to is our history especially the Liberation Movement because it is something very close to home. Our parents still remember stories from 1971 and I guess for me, it is something to be proud of.”

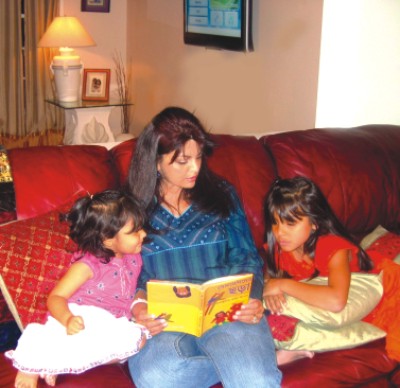

Bangali families getting together on special occasions

gives them a sense of being closer to home

Shushma who comes to Dhaka every year enjoys taking part in music and dance programmes wherever they take place. “I participate in musical events and concerts that happen every month and it's a way to bring Bangali culture to the United States,” says Shushma, “I now wish I had spent more effort learning Bangla more fluently in terms of reading and writing because I appreciate its value more now that I am older.”

For Zabin F Mansoor, a consulting engineer who has been living in the US for 16 years the bond with her Bangali identity could not be stronger. “The deep rooted tradition, richness of the language and literature, the traditional clothes, the delicious food, the warmth of the people draws me to my country,” she says.

For Zabin and her husband it is extremely important that their two daughters understand their heritage and pass on the traditional values through the generations. “This is a melting pot of a variety of cultures and we do not want them to forget theirs,” says Zabin, “we do not allow our children to speak in English when we are home. They enjoy watching Bangladeshi programmes through the two very popular Bangladeshi TV channels that we subscribe to. It helps them with exposure to the way of life in Bangladesh. I cook traditional food in the house as often as I can so they can grow the taste for it. I read Bangla books to them and teach them little poems and songs.”

Zabin also tries to teach her eight-year-old daughter about the history of the War of Liberation in simple terms for her to grasp. “I don't get to go to Bangladesh as often as I'd like to,” says Zabin, “but we try not to make a huge gap between visits so it is not a culture shock for them when they go to Bangladesh.”

Zabin encourages her daughter to speak in Bangla at home

Zabin says that she and her husband constantly feel an urge to maintain their Bangali identity. “We try to celebrate festivities like Pahela Baishakh, Bijoy Dibosh, Ekushey February etc with whatever means we have.

“Once the students association here arranged a Shadhinota Dibosh Udjapon in the campus auditorium where we began the celebration by viewing some rare footage of the liberation war, then enjoyed some authentic Bangladeshi food that every family contributed to, and later enjoyed an informal cultural programme by some of the local talents,” says Zabin, “and on a couple of occasions we have set out Bangladesh stalls in the international festivals and showcased our unique handicrafts.”

“We might have crossed the boundary of Bangladesh, and wear different clothes and speak in a foreign language at work but we do not forget that we hail from Shonar Bangladesh. We are like the cheerleaders of Bangladesh in the western hemisphere,” she adds.

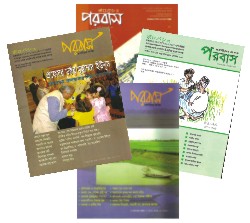

It was on February 21, 2003 when a few Bangladeshi friends decided to bring out Porobash,

Kazi Ensanul Hoque, the Editor of Porobash, organises cultural activities for Bangalis living in Japan |

a magazine for the expatriate Bangladeshis living in Japan. Kazi Ensanul Hoque, the current editor of Porobash along with his friends Rahman Moni, Badrul Borhan, Baker Mahmud, Motaleb Shah and Shajal Barua Pramukh, have been living in Tokyo, Japan for more than two decades. The Japanese culture is now a part of their daily lives, for instance the language that they speak, eating habits and so on. However, the bi-monthly magazine, which is published in both Bangla and Japanese, caters to the Bangladeshi expatriates with write ups regarding Bangladeshi politics, music, arts, nutrition, cooking, sports and many more. “The magazine even has a section where the Japanese people can learn Bangla,” says Ensan. “The magazine is subscribed not only by the expatriate Bangladeshis and the Japanese, but also by other nationalities living in Japan.” This Japan-based Bangla magazine started its journey initially as a community publication. Due to the huge support from readers and gaining a lot of popularity, Porobash eventually grew bigger and began to reach people beyond their small communities in Japan and elsewhere.

“We have a very hectic life here in Japan,” says Ensan, who is also the local representative of Shaptaik 2000 in Japan and is enlisted with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Japan as a foreign correspondent. “It is probably this effort to express our thoughts and feelings in our very own language, our culture and customs that relieves us from the agony and the nostalgia of those left behind thousands of miles away.” A very popular personality amongst the NRBs in Tokyo, Ensan is also actively involved in organising cultural activities for the expatriates living there and elsewhere in Japan. Like every year, this year he, along with others in the community, will organise the Tokyo Baishakhi Mela.

“Both the Bangladeshis living in Bangladesh and Japan and the Japanese writers and artistes are involved in the making of the magazine, where a blend of the two cultures develops and is highly encouraged” says Ensan.

Ruby Rahman, a mother of three, has been living in Toronto for the last 14 years. She left Bangladesh in the late 70s, at a very young age right after getting married to an engineer. Since then, she, along with her husband has been moving from one continent to another owing to her husband's job postings. By the time she finally settled down in Toronto after a decade-long stay in the Middle East, two, out of her three daughters were grown up and university students. Her daughters had never actually lived in Bangladesh, if one doesn't count the summer vacations that they spent in the country every two years, and had grown up in a multi-cultural environment with Paksitanis, Indians, Arabs, Chinese, Americans and Canadians. In spite of this, all three of her daughters speak, read and write fluent Bangla, a fact, which is quite rare especially amongst the first generation immigrant Non Resident Bangladeshis. “My daughters went to international schools all their lives,” says Ruby.  “However, I made an effort in teaching them Bangla during their yearly vacations ever since they were very young.” In fact, when Ruby was residing in Iran in the early eighties, friends would send their children to her every other weekend for Bangla lessons. “I would teach my 4-year-old daughter Bangla during weekends,” she says. “A friend of mine wondered if I could manage two more aged 4 and 5, who also happened to be my daughter's play mates. I was just too happy to comply. Eventually, a lot of children started to come to take Bangla lessons.” “However, I made an effort in teaching them Bangla during their yearly vacations ever since they were very young.” In fact, when Ruby was residing in Iran in the early eighties, friends would send their children to her every other weekend for Bangla lessons. “I would teach my 4-year-old daughter Bangla during weekends,” she says. “A friend of mine wondered if I could manage two more aged 4 and 5, who also happened to be my daughter's play mates. I was just too happy to comply. Eventually, a lot of children started to come to take Bangla lessons.”

Teaching Bangla at home eventually grew into an establishment. For the last 10 years, Ruby has been holding weekly Bangla classes for Canadian born Bangladeshi children of all ages. She even has an assistant to help her out with the classes. “It's natural for children to avoid learning new ideas and languages,” says Ruby. “Especially with our children here to whom learning Bangla sometimes becomes a burden. All I tell them is to take Bangla as just another foreign language that they learn at school, for instance French or Spanish.”

It was a very difficult decision for 50-year-old Fahmida Rahman, a Rabindra Sangeet exponent, to leave her country and migrate to an unknown land. “Often one is driven by ambition, a search for new opportunities or in some cases by a yearning to expand and grow mentally and intellectually,” says Fahmida. When Fahmida immigrated to the United States with her children she was motivated by ambition and adventure that the land of opportunities offered. “We were happy that we were giving our children a great opportunity to see the world and explore new horizons. However, with time we realised that we were also taking away something precious from them their sense of identity,” says Fahmida.

Fahmida believes that when adults move to a new country they have an advantage of never living in ambiguity in their childhood and can start a new life with their ethnic/national identities. “But children who are uprooted and brought to a new culture have a harder time they are forced to live a dual life. They are torn between two worlds one at home with their parents who still have their strong cultural roots and the other in the outside world which in many ways is different. They have to cope with two languages, accents, cultures and sometimes different values,” she adds.

|

| Through Bangla music and the art forms, the Bangalis living abroad find it easier to stay connected |

Photo: Drishtipat |

“We parents think it's important to make our children aware of their roots because, despite all the changes that we are exposed to, we still believe that our strongest bond is with our own culture and language. Some of us who have lived in the US for 20 years still dream in Bangla or we are overcome with nostalgia when we hear a Tagore song. We long for the monsoons and the autumn sky of Bengal. The sight of the cherry blossom in the tidal basin of Washington DC reminds us of the Krishnachura in Ramna, Dhaka. With time we realise that a Harvard degree has given us intellectual growth, but the strains of Bangali music gives us a sense of belonging. Despite all our efforts to call football soccer and enjoy the Jay Leno Show in NBC we are happiest when we discuss cricket or watch a sentimental Bangla natok. We then go through self-questioning how can we deprive our children of their Bangali identity? An identity which has given us so much and is such an important part of who we are even in this multiethnic melting pot of a country? This is what inspires mothers like me to try to expose our children to Bangali culture even in the remote US. After all it is a wonderful thing that they can learn to be multifaceted. They can enjoy the culture and language of the US and also that of their roots. Their lives can be so much richer because they can appreciate and accept a new culture as their own and yet have the knowledge and understanding of another culture, which is part of their parents and grandparents. By teaching our children Bangali music and culture we raise their consciousness as Bangalis. In the greater scope of things this helps them develop their other consciousness that they are a tiny part of this all-encompassing world. It helps build tolerance and acceptance for people who are different and makes them more complete human beings.”

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |

|