| Human Rights

Waiting for Justice

She advised other women to leave their abusive husbands but when her own

husband turned violent, she put her fear of social stigma and her daughter's

happiness before her own.

Hana Shams Ahmed

|

No one knows how Shaptorshi is spending her days without her mother's care. |

It was the eve of Eid-ul-Fitr in 2005. Nine-year-old Shaptorshi had just come back from Dhaka to celebrate the big festival at her dadi's house in Barisal. After playing with her friends, Shaptorshi came home to eat iftari and was told that her mother Papia was not feeling well and was resting in a room upstairs. She decided to go to her uncle's house next door to have iftari and then rushed to the rooftop with her friends. After catching a glimpse of the new moon she rushed home to share the excitement with her family. She never got to hug her mother though. Right after sighting the new moon Shaptorshi's little world fell apart when she was told that her mother was no longer in this world.

Dilruba Haque Papia fell in love with her cousin Mamun Morshed Tuhin and after completing her Masters from the Law Department of Dhaka University married him against her family's wishes in 1994. She later joined the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) where she worked until her death on November 3, 2005. From the very beginning of their marriage Papia was not very happy with her husband. He had never gone to university and did not have the educational qualifications needed to get a decent job. In 1996 Papia gave birth to a beautiful girl Shaptorshi and continued to work. Tuhin gradually made himself comfortable on his wife's income and got into a habit of drugs. He also turned violent. Tuhin lived in Barisal with his extended family under one roof but Papia would come and live at her mother's house in Dhaka for long periods of time. Many times her elder sister Mahbuba Huq Kumkum who works at Acid Survivor's Foundation (ASF) would find unexplainable marks on her body. If she asked her about it, she would shrug it off as some mishap she had in the house. One day following an argument at Papia's mother's house Tuhin cut his own hands and started shouting that his mother-in-law attacked him. Tuhin's activities disturbed the peace of the whole family but still Papia could not think about divorce. Her elder sister Kumkum was a divorcee and it affected Papia a lot. What would society think if both sisters were divorced, she would say on many occasions. And Shaptorshi adored her father. Papia could not think of separating him from Shaptorshi. "She was like a typical girl in our society with two faces a public one where she showed everyone that she was really happy and the other one where she was really unhappy but no one knew about it," says Kumkum.

But this 34-year-old lawyer who fought passionately for women's rights and advised women to punish their abusive husbands made the fatal choice of staying on in her own abusive marriage. Papia had talked to her sister before leaving Dhaka that she could not bear Tuhin any more and the only way out of her ordeal was for her to leave the country. Kumkum asked her to stay calm and said that they would talk about it after Eid. The night before she died Papia and Tuhin were overheard having a violent row inside the launch they took to go to Barisal from Dhaka. Shaptorshi, who was very attached to her aunt Kumkum, confided in her about the argument over the phone.

|

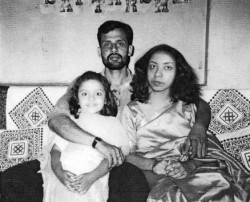

Papiya (right) with her husband and daughter. She married for love with no idea what she was getting herself into. |

On the morning of November 3 Papia talked to her friends. She was not well. She had recently been suffering from Herpes and was taking medication, which made her weak and feverish. In the evening a boy from a neighbouring house called up to tell Kumkum that Papia was dead. Papia's elder brother, who is mentally challenged and needed constant care, was looked after by Kumkum, who could not leave him and go to Barisal. Her younger brother Annu went and Kumkum constantly kept communicating with Tuhin's family over the phone. She smelled foul play when his family members kept giving contradictory statements over the phone. One said that she had died of a stroke. “When I asked how they knew and whether a doctor had said it they said no,” says Kumkum, “another one said that she had died of breathing problems and all the members of the family kept on emphasising on one point that she got dressed all by herself, walked to the rickshaw and went to the hospital.” But that contradicted with two eyewitnesses who saw her being carried in a rickshaw covered in white clothing; Papia, moreover, had never suffered from breathing problems before. “I knew what Tuhin was like, he had a habit of trying to muffle her sounds (if she shouted) by thrusting a pillow on her face,” says Kumkum.

Kumkum immediately asked her younger brother to file a criminal case with the police and get an autopsy done of Papia's body. The police refused to file a case and an autopsy could not be done. When Kumkum asked Annu to bring the body back to Dhaka for an autopsy, Tuhin started to panic. “At first he started saying that it was not religiously correct to do an autopsy on a woman's body,” says Kumkum, “then when I insisted on it, he said that Annu wouldn't be allowed to return if he tried to do that. He was also standing there with a boti to prevent Annu from talking to Shaptorshi separately. I felt really intimidated and told Annu to come back to Dhaka immediately and forget the autopsy.”

But pressure from NGOs and human rights activists forced the authorities to take up the case and the body was exhumed five days after her death and an autopsy carried out on the same day. “We had to stand for almost eight hours in the morgue for the report so that it wasn't manipulated in any way,” says Kumkum. In the preliminary report it read tongue out (which indicates strangulation), vaginal area mutilated, injury with a blunt instrument on the lower part of her left knee before death. The final report was delivered after four months. In that report the verdict was that the body was highly decomposed which contradicted with the preliminary report where her nails and hair were still intact.

Almost two years have passed since Papia's death. The Investigation Officer has been changed three times since. The case has been handed over to CID but there has been little in the way of progress in the case. One witness who saw Papia's body being carried in a rickshaw by two women refused to say so in court in fear of retribution. Accounts of those eyewitnesses were taken who said that they did not see anything. Someone from a neighbouring house said that her husband and his sister were pounding on something with their feet. On November 7 police arrested Swapna from Tuhin's College Road residence following pressure from local human rights organisations and publication of reports in newspapers. Tuhin was also present in the house when Swapna was arrested but fled in full view of the police. Kumkum alleges that Tuhin's affiliations with local politicians have so far kept him above the hold of law. “I went to Barisal with a lawyer from ASK and we were chased away from there, and had to spend a night in Faridpur,” says Swapna. Not satisfied with the mother's death, Tuhin's family is now messing with little Shaptorshi's life.

Papia's mother filed a case for Shaptorshi's guardianship as her life was thought to be in danger in her paternal grandmother's house being the lone witness to her mother's murder. Shaptorshi came to court and pointed directly at Kumkum and said that she did not want to go to her because she was lying about her dad. “The judge at the family court took us aside in his own chambers for a couple of hours,” says Kumkum, “and there she said in front of the judge, 'I want to come to Dhaka and I want to study in a good school. I don't want to go back to Barisal.' On this basis the judge said that she would be taken to Dhaka the following January and admitted to a school there and stay with me. After going back to Barisal she completely changed her statement and said that she did not want to come to Dhaka at all.”

Instead Shaptorshi was taken to a government 'safe home' under the Barisal Social Welfare Department but was later taken back to Tuhin's family's house. The following year, Papia's mother also died unable to bear with the shock of losing her daughter.

“If she would just once say in court that she wanted to stay with me,” says Kumkum, “we could have rescued her. I don't know what fear is stopping her from doing so. For some reason she is under the impression that she will be able to come to Dhaka as soon as the case against her dad is lifted." Kumkum is extremely worried about Shaptorshi's well being. "No one is educated in Tuhin's family. Her father and uncle are drug addicts. In their family girls are married off before they reach adulthood. The family used to run on Papia's money. They can't afford to bring her up the way she is used to. They are only keeping her there because of what she might disclose to us."

But Kumkum is adamant to see a conviction in this case. She knows there is evidence and there are eyewitnesses that can convict Tuhin and his sister for the murder of her sister. Her fight will go on until then.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |