| Cover Story

The Fight for Information

Nader Rahman

The United Nations General Assembly recently acknowledged freedom of information as a fundamental right and thus helped legitimise it as a fundamental right even if it wasn't explicitly mentioned in the constitutions of countries around the world. The Right to Information gives people the legal right to attain any information from the government for their personal or business purposes. It is based on the fact that the government is elected by the people and thereby works for the people, by paying taxes the average citizen is entitled to find out and be given proof of what the government does with his/her money. It is basically a system of accountability and transparency that hands some degree of power back to the people. But it is not merely a tool for people who take a keen interest in the inner workings of a government; citizens can also seek information from appropriate duty holders, who are in turn bound to distribute important information, in some cases even when they are not asked. The United Nations General Assembly recently acknowledged freedom of information as a fundamental right and thus helped legitimise it as a fundamental right even if it wasn't explicitly mentioned in the constitutions of countries around the world. The Right to Information gives people the legal right to attain any information from the government for their personal or business purposes. It is based on the fact that the government is elected by the people and thereby works for the people, by paying taxes the average citizen is entitled to find out and be given proof of what the government does with his/her money. It is basically a system of accountability and transparency that hands some degree of power back to the people. But it is not merely a tool for people who take a keen interest in the inner workings of a government; citizens can also seek information from appropriate duty holders, who are in turn bound to distribute important information, in some cases even when they are not asked.

But the government is not the only institution that is answerable to the public, many international institutions which effect and influence public rights along with the lives of innumerable people are also under the purview of the law. If effectively implemented the act could have far reaching consequences, effectively bringing back the power to the people of a nation. But while this is the view of what it can achieve, in Bangladesh the process of getting a Right to Information Act has been quite long and drawn out. And against everything it stood for, the act was shrouded in secrecy and to date has never seen the light of day.

|

Sanjida Sobhan, Coordinator (Governance), Manusher Jonno. |

In 2002 the Law Commission drafted a working paper on the Right to Information Act and it seemed that finally the government of Bangladesh had come up with a viable plan to make itself more accountable to the people of the nation. It was a false start as eventually the cripplingly ineffective Law Commission's working paper remained just that, a working paper which was thought up to fool the public into a false sense of security. When making major legislation such as a Right to Information Act, this act in particular should never be wholly constructed without the public's input because eventually they will be the ones using it their voices should be heard and to a certain extent complied with. But for the immediate past government it was nothing more than an eye wash, they did as little as they could to garner a reasonable level of public support and in the process put together a very scratchy and basic outline to a Right to Information Act, without the intention to appease public demand for it.

The draft served its purpose as the government proudly waved its hands to the public saying that they were true to rooting out corruption, soon the hands came back to their normal position somewhere under a desk in a government office picking up the day's bribe. While it was a laudable effort then, only now in hindsight can we see how it merely served the purpose of the government, ironically this was what the law would have protected the country's citizens from. Rightfully they could have questioned the government what was going on with the law, when it was going to pass and if any major amendments were going to be made, but it never turned out that way. Five years and numerous embarrassing Transparency International rankings later the government of the country is strangely not answerable to the people who elected them, leaving us with nothing more but a broken shell of democracy.

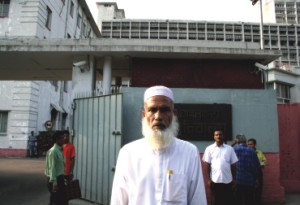

|

For the average citizens, access to government files is severely restricted, leaving them without hope. |

Since the promise of unhindered information in 2002 the citizens of the country have galvanised in the past five years many organisations have taken the proposed law to heart. They wish to see it officially become a law and have worked extensively to bring their dream to the consciousness and reality of the entire nation. One could possibly say the leader in such activities is the organisation Manusher Jonno, which promotes human rights and good governance. The Executive Director of Manusher Jonno Shaheen Anam says “The Right to Information Act is nothing ludicrous or out of this world, it is a very simple right for the citizens of a nation that the government of a country should be accountable for their actions.” She goes on to say “In Bangladesh the situation was rather dire, the people were shown a glimpse of the Right to Information Act and then when it came to the consciousness of a number of people it was never followed up on.”

Most people contend that it was a mistake to talk about it and parade it about without following through, because then the government created a situation where people knew about it, wanted it but were frustratingly left to wait for it indefinitely. In the years that followed whenever corruption was mentioned the fact that the Right to Information Act was never even tabled in parliament was constantly mentioned and the immediate past law minister had to defend himself on quite a number of occasions when asked about the topic. Anam went on to say “Manusher Jonno took the lead to push it forward in 2005, when we reviewed the draft act that was handed in to the Law Ministry by the law commission. The draft was reviewed and gaps were identified.” While the majority of people interested in the first draft in 2002 were just happy that a law for the right to information would come into effect, few if any knew how horribly flawed the draft itself was. “It was only after receiving a copy of the first draft did we realise how much work was left to be done", explains Anam. "There were major areas that needed to be looked into and rectified and Manusher Jonno took it upon itself to do so. Eventually another draft was prepared and quite recently we submitted it to the Law Ministry where the reception has been favourable. We hope that it will become an ordinance soon, and in time will be ratified by parliament and become a law.”

|

Government officials have been notorious for withholding information. |

While the mere mention of a draft law was enough to keep people happy temporarily, the draft itself turned out to be quite backward. While it was supposed to increase the amount of information available to the public in fact it did not live up to its reputation. It was basically an outline on how to make it seem that governments could and should be held accountable for their actions and there was little if any substance to the draft at all. In the end the public was fooled by the mere mention of a draft, thus proving how the citizens of a nation were starved for a real working democracy. To be specific the draft act included and ratified the Official Secrecy Act, 1923. That was the topic of most contention: If one is looking for maximum disclosure exactly how can that be achieved by including an act that actively subjugates the people and makes no bones about the minute amount of information that should in the public domain?

Along with the Official Secrecy Act, there were still some rules where the government was not bound to hand out information, by hiding behind the state security and safety excuse. Most worryingly there was no way to enforce the act, as the draft proposal interestingly left that out. That leads one to the assessment that even if the act was tabled and passed by parliament, it was prepared in such a manner that the law would exist but there would be little if any implementation. That coupled with the inclusion of the Secrecy Act gave the government essentially full control over the access to information. They had planned for every possible situation and if it were passed it would have been shambolic. Luckily enough it was never even tabled and five years later it is the people who have spoken. They demanded a free, fair and pro-people Right to Information Act and that process is well on its way.

|

Pranab Saha, Chief Reporter, The Daily Prothom Alo. |

Sanjida Sobhan Coordinator (Governance) for Manusher Jonno has been heavily involved in the whole process of turning the 2002 draft into a law that can and will stand the test of time. She says, “It is important to step out of the shadow of corruption that has plagued the country and this Right to Information Act could be a major step. But even if the law is passed there is much that needs to be done regarding the state of transparency in both government and other major institutions.” What is often forgotten about the act is that it is people-centred and the main beneficiaries of such laws will not just be people in the urban areas of Bangladesh. This law probably holds more importance to the rural villager or farmer more than anyone else. “It is linked to the to the livelihood of many groups of vulnerable people" says Sobhan. "This benefits the poor most of all because they must know what schemes are being taken to help them. There are innumerable development schemes in aid of the poor, yet the poor have no idea about them. Why is that? It is their right and the government's duty to show all documents and disclose all information regarding the projects. By doing so they are empowering the poor, not just giving them a hand out.”

The process to change one wayward draft into a viable law was long and difficult. Sobhan says “Based on the working paper given to us by the Law Commission we put together some core groups of people who would help us sharpen it. The process was systematic we asked some simple questions and in answering those questions our version of what they should have been came about. Questions like what should the law include, where were the faults in the current framework and how could it be turned into a proactive and efficient law. By the time the core groups answered those questions we had worked out all the faults of the first law.” The next step was to take to the people around the country and take their feedback, after all this was a pro-people law and they should have something to do with its formation. Sobhan says, “We then arranged regional consultation meetings in Chittagong, Khulna, Rangpur and Dhaka where we decimated the law amongst lawyers and civil society members for their input. Based on their recommendations we then revised the law again so that it included the average citizens input and then finally finished it. There were many people who helped turn the working paper into what we submitted but from the multitudes Advocate Sultana Kamal, Advocate Shadheen Malik, Professor Asif Nazrul, Advocate Alina Khan, Dr Shamsul Bari and last but not least Barrister Tanjib ul Alam stand out for their hard work and dedication towards the cause.”

|

The right to information is essential for good governance. |

While Mansusher Jonno took the initiative that the government did not, they were simply following in the footsteps of other regional countries that took the right to information seriously. India passed their own Right to Information Act in May 2005 but not before a massive movement took place, the same kind of movement needed here if the law is to be practised successfully. The rights defined the act in India are clear-cut and for the most part the enforcement of the law has been courageous. Information concerning the life and liberty of a person must be divulged within 48 hours while other information is given up to 30 days. They have also set up a commission lead by a chief information officer who oversees the cases that require arbitration. This has proved to be highly successful and is a measure that should be and is proposed to be replicated in Bangladesh.

While the Right to Information is said to be mainly for the average person, journalists and media industry should find the move particularly heartening. In Bangladesh they have had to suffer long enough, desperately seeking information from government offices, usually without so much as a one-word answer from them. Pranab Saha the chief reporter for The Daily Prothom Alo sheds some light on the situation, he says, “The media have a lot to gain from this law, for years now the struggle for information has been especially hard on us. With this new law whistle blowers will no longer need to bribe for the information they desire, it will all be available and it will surely be a great resource for the whole media industry.” He went on to say “Journalists in America praise us for being fearless, but why should that be the case? Why should an investigative journalist have to put his life on the line for some information? Currently there are no specific laws that protect journalists in Bangladesh and that also needs to be looked into, if the law is passed it will give them a little protection. In America the dissemination of information is great, here for simple facts our lives are threatened. What are the governments trying to hide? If they are as open and transparent as they claim, this act should be nothing for them, yet it took more than five years for anything substantial to occur. That too people from outside the government pushed the cause."

|

It is a simple right for the citizens of a nation that the government of a country should be accountable for their actions. |

“I am very optimistic," continues Saha, " I feel the law will happen it has worked well in India, why shouldn't it do the same here. But aside from the media and the average man this law would greatly benefit the NGOs. If they take it up seriously and to heart there will definitely be a trickle down effect which will help the average man living in a village.” But even Saha feels just a simple law will mean nothing, it should be effective and work properly. There is a risk that there will be no implementation of many laws one hopes this will not fade away into the background. Saha also adds how the right to information law could help deal with the current price hikes, he says “Price hikes occur as a result of speculation, if there were documents that could be accessed then some of the price hikes could be questioned. An example is that when oil prices go up around the world, our government justifies the price hike by pointing to world market trends. If information was available maybe one would find that the oil being sold now was bought three months ago, before the surge in world prices. If that is the case, till they finish using the old oil, they should rightfully charge the lower price. And most of the price increases now are due to speculation, if all the information was in the public domain and easily available I really do believe prices would not have gone up by the amount that they have.” One of the basic criteria for good governance is the right to information, and here in Bangladesh this could set the standard for all future governments. But there are many factors to look at before we celebrate its success. With the current government in power it will only come into effect as an ordinance, the next elected government will table the issue in parliament and there is the chance that if we return to the politics of old it will not be passed. That would be catastrophic for the cause, even worse would be simply allowing the law and not enforcing it. There is one option now, and that is to educate as many people as possible about it. If they simply know about the law, for the time being that should be good enough. In the future they can exercise their right to enforce it. As Shaheen Anam says “The media have a major role to play in spreading the word of the Right to Information Act and they also stand to gain immensely from it.”

If it is a transparent, democratic nation we are so passionately striving for including the Right to Information Act is a prerequisite. People must know about this potentially empowering tool and any future democratically-elected government that needs to prove its credibility is morally obligated to make this act a reality.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |

|