| Cover Story

Learning on a Boat

Hana Shams Ahmed

Photos: Zahidul I. Khan

Riya, Afia and Kulsum are all six year olds and very excited about their first time in school. The three shy, giggly girls shout out the Bangla alphabets from their shiny new books in unison with the rest of the class. Their tattered clothes and dirty faces cannot take out the thrill they wait for at the end of the class when they will be able to watch their favourite Meena Cartoon on the computer screen next to the teacher.

Their mothers, barely in their twenties, wait outside the classroom, their skin tanned from working out in the sun for long, gruelling hours in a village that is far removed from the high-rise buildings and flashing shopping malls of the city. Clad in simple cotton saris that have seen better days and wearing two golden nose rings as is the tradition here, they are just happy that their daughters are getting an opportunity that they never had. Passers-by give curious looks at the noises coming from the classroom. This, after all, is no ordinary classroom. Riya, Afia and Kulsum come from one of the country's poorest villages in the northern part of the country along the Chalanbeel region and the classroom they are sitting in is inside a custom-made boat with solar-powered panels on top.

Known popularly in the region as the 'Boat School', these boats, a novel approach of Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha, have been wading through the waters of the Chalanbeel in the Pabna, Sirajganj and Natore districts. The villages around the Chalanbeel are the worst affected areas during the monsoon season every year. Most of the schools, and the paths leading up to the school, go under knee-deep water and remain closed for months, which lead to a high dropout rate every year. There are many families who prefer to have their daughters work at home instead of sending them to school. Known popularly in the region as the 'Boat School', these boats, a novel approach of Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha, have been wading through the waters of the Chalanbeel in the Pabna, Sirajganj and Natore districts. The villages around the Chalanbeel are the worst affected areas during the monsoon season every year. Most of the schools, and the paths leading up to the school, go under knee-deep water and remain closed for months, which lead to a high dropout rate every year. There are many families who prefer to have their daughters work at home instead of sending them to school.

The boats are designed by Shidhulai to adjust to any equipment configuration as well as to protect the electronic equipment from inclement weather, even during the height of the monsoon. Flat-plank floors allow the boats to glide on very shallow water of small canals. The Shidhulai boats are also outfitted with multi-layered waterproof roofs and side windows that open in good weather.

From a single boat in 2002, that provided very basic education to girls who had never been to school before, the project now has about 35 boats where both boys and girls can study up to the third grade. The floating classrooms are handsomely equipped with a computer and multimedia peripherals where the children can not only watch educational videos but can also learn basic computing functions. The shiny new alphabet book that Riya is reading out from is also not the conventional book that most primary school students follow. The alphabets are illustrated with cartoons of places and objects relevant to the village tube wells, clean toilets, irrigation pumps and birds and fishes on the verge of extinction.

Jasim is one of the few boys in the class. He already has a good grasp on the alphabets and enthusiastically spells out the name of the animals in the books. Although Jasim is eight years old he has never attended school before. “My house is quite far from the school,” says Jasim shyly, “but the boat comes and picks me up from near my house and I am enjoying school now.” Jasim is one of the few boys in the class. He already has a good grasp on the alphabets and enthusiastically spells out the name of the animals in the books. Although Jasim is eight years old he has never attended school before. “My house is quite far from the school,” says Jasim shyly, “but the boat comes and picks me up from near my house and I am enjoying school now.”

The young teacher Salma Khatun, who got married after completing her SSCs used to be a housewife before joining Shidhulai's boat school. Besides taking Math, Bangla and English for first graders she also goes around the village encouraging parents not to take their children off school and see if they are studying at home or not. At the sight of visitors she enthusiastically directs everyone to sit straight, speak loudly and behave themselves.

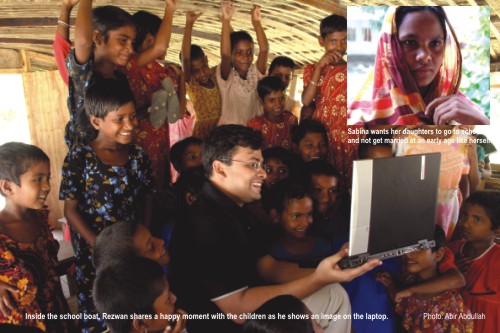

A young shy mother of two daughters, Sabina stands outside the boat school and waits for her six-year-old daughter to come home with her. Although she didn't go to school herself she understands the importance of her daughter's education. “I make sure she goes home and finishes her homework,” says Sabina whose husband is a farmer, “I don't want her to get married so early like I did.”

But there are still many parents in the poor areas of the north who prefer that their children stay at home and help with housework or other agricultural activities. For them Shidhulai has set up night schooling on the boats. The classrooms inside the night school are illuminated with batteries charged with solar panels. But the purpose of the batteries is not limited to that. Besides providing power supply for the computer and related equipment on board, Shidhulai's Portable Solar Home Systems (PSHS) generate electricity to the nearby village homes which earlier only used lights from 'kupis' and 'hurricane lamps'. The system uses a 4 Ah lead-acid battery to power two or three LED lamps for 30 hours. The boats deliver the batteries and two lights (one is a hanging bulb and the other is a small reading lamp) to the houses of the poorest of the neighbourhood, especially ones where there are students who find it difficult to study by the weak lights of the 'hurricane' lamps. Every week the boats revisit and replace the batteries with another fully charged one. The manufacturing cost of a PSHS is only Taka 350 and is manufactured by the villagers.

Nazma Begum's son is an honours student and her daughter is studying for her HSC exams next year. Her poor farmer husband cannot afford to pay for electricity in their modest home. “These people came and asked me if I had children and then gave us lights for free,” says Nazma, “earlier it was very difficult for them to read by candle light and I could not stitch my kathas after dark. I never imagined having a light like this in my house." Her only complaint is that her children get into quarrels sometimes because they have to study in the same room. According to UNDP, 74% of Bangladeshi households in the villages do not get electricity.

Shidhulai has come a long way from just providing basic learning programmes for children. Twelve of their boats are fully equipped libraries which complement the study programmes of SSC and HSC students who are too poor to buy their own books. Seven copies of all the books under the school and college Board, including the guide books, can be borrowed by students in the locality and kept for up to a week. These libraries are also equipped with computers, which have Internet access, and three-month-long basic computer training courses.

At the boat library Mohammad Milon Rana who is an SSC candidate is leafing through a guidebook. It's not possible for his farmer father to buy all the books in the syllabus so he spends a good bit of his time at the boat library. “I already have two books at home and I'm just looking at what the new guidebooks are saying,” says Rana. Tania, who reads in class seven prefers to borrow some of the interesting story books on board the boat library, while Shathi, another SSC student is learning to operate the computer for the first time in her life. The boat library also gives the young people opportunities to interact with each other outside school premises which is unthinkable in such a conservative society.

In another boat a projector is being set up beside a computer. On the screen a slideshow illustrated photos of insects labelled 'good insects' and 'bad insects'. About 20 villagers, both men and women are sitting opposite the projector screen learning about environmentally friendly methods of agriculture. "What happens when you use pesticides to kill the harmful insects?" shouts out Sajjad Hossain, the instructor, from one end of the boat. "The good insects get killed too," answer back the men and women in unison. Hossain, who has a post-graduate degree in agriculture, then tries to get in touch with villagers from another boat, who had located some problems with their brinjal cultivation. He looks at the brinjal on his computer screen through the video-conferencing component of Yahoo Messenger and tries to solve their problem. In another boat a projector is being set up beside a computer. On the screen a slideshow illustrated photos of insects labelled 'good insects' and 'bad insects'. About 20 villagers, both men and women are sitting opposite the projector screen learning about environmentally friendly methods of agriculture. "What happens when you use pesticides to kill the harmful insects?" shouts out Sajjad Hossain, the instructor, from one end of the boat. "The good insects get killed too," answer back the men and women in unison. Hossain, who has a post-graduate degree in agriculture, then tries to get in touch with villagers from another boat, who had located some problems with their brinjal cultivation. He looks at the brinjal on his computer screen through the video-conferencing component of Yahoo Messenger and tries to solve their problem.

Most of the students at today's class are women who want to set up vegetable gardens in their own back-yard to meet their family needs and also to create their own income source. Rizia Sultana and Jannatul Ferdous are one such mother-daughter duo who are learning about the proper usage of fertilisers for use in their vegetable garden. "We always do the classes here, says Rizia, "the vegetable garden has really helped with our home income."

Once a week a group of scientists from the Sugarcane Research Institute joins through videoconference and answers questions from the villagers and instructors. The training sessions take place about twice a month and are two or three days long.

At the helm of the 'Boat School' project is a man who has grown up in the Chalanbeel area, in the village of Shidhulai, and has seen first hand how the people in the area struggled to get on with their daily lives. thirty-three-year-old Abul Hasanat Mohammed Rezwan passed his SSC and HSC exams from Shidhulai before graduating in Architecture from BUET in 1998. Instead of going abroad to pursue a career in his line of studies like most of his fellow graduates, he decided that he could make a much bigger difference to the people who were a big part of his life while he was growing up. Ever since he came up with the initial concept there has been no looking back for Rezwan. It took two years for the first boat to sail through the waters of the Chalanbeel. It was not an easy journey. Rezwan invested his scholarship money into the project at the initial stage. Afterwards various corporations came forward with their helping hands and after winning the Citizen Based Initiative Award of Ashoka in 2002, the project gained further momentum.

"Bangladesh is a river-centric country. Almost 90% of the flow of the Ganges, Jamuna and Brahmaputra go through Bangladesh everyday," says Rezwan, "and we see every year how during the monsoon season one-third or sometimes two-thirds of the country goes under water. Under such a context, and growing up in that area I had to do something for the people from my village."

"The water and the boats are a part of the lives and livelihoods of the people from these areas," says Rezwan. He points out that there are many schools that go under water every monsoon and people are even unable to ride a bicycle through the roads because there is so much mud. "In these areas the only way to go from one place to another is by boat," says Rezwan, "So they are being deprived from information and basic amenities."

"The development strategy for Bangladesh is that all development work is road-centred. As such the river-centred people are deprived from a lot of things," says Rezwan, talking about the commencement of the project, "so we thought that whatever activities we were going to do should be centred around the river. It started out as just providing the basic schooling and gradually moved on to other things. Because of Internet people can read the news online and students can get their SSC and HSC results online too. Solar energy was used to make the programme self-sustained because diesel generators are expensive and harmful for the environment."

When they started out the existing country boats were used to conduct classrooms. "The teachers had to sit outside and it was very inconvenient especially when it rained," says Rezwan, "so we customised the boats to accommodate all the activities. We also had to change the curriculum for the children of the river basin area."

"People didn't take on the idea of the boat project very easily at first," says Rezwan, "The school teachers played a big part in motivating them."

Shidhulai has won several international awards and recognitions for their innovative project, including the Ashden Awards/Green Oscars 2007 (UK), UNDP's Equator Prize 2006, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Access to Learning Award 2005, Global Junior Challenge Award 2004 of the City of Rome (Italy), Intel Environment Award 2004 of the United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank Institute and Santa Clara University, Recognition Award of the World Bank's Development Marketplace 2005, second prize of Stockholm Challenge Award 2003/04 of the City of Stockholm (Sweden), Global Social Benefit Incubator 2005 & 2006 of Santa Clara University, Entrepreneur 2006 of Global Philanthropy Forum (U.S.) etc. In recognition to its success Institute of Chartered Financial Analyst of India (ICFAI) and Santa Clara University included Shidhulai projects in their educational curriculum. So far Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha has received more than 15 international awards and certificates of recognitions from different countries.

Rezwan's next plan after this year's devastating floods is to build a floating housing project. "It could work as a flood shelter," says Rezwan, "and could also give shelter to people who don't have anywhere to stay. "We are working on developing strategies on how the project can be made more community-based. They work better because they understand the local problems more, instead of the NGOs." Rezwan says that he encourages a bigger implementation of the project which would make perfect sense for a country like Bangladesh which is at the top of the list of the countries that stand to be affected by global warming.

With the temperature rise leading to increased deforestation and Bangladesh being a land mass which is on average no more than 10 metres above sea level, according to environment experts, an 89cm increase in the sea level would eat up roughly 20% of Bangladesh's landmass, displacing more than 20 million people. The innovative efforts from Shidhulai are crucial solutions in the wake of such devastating predictions.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |