| Cover Story

A Trail of Death

Hana Shams Ahmed

A trail of devastation where once used to be homes, crops and hopeful farmers and joyful families. Now there is just the stench of death. PHOTO: SHAFIQ ALAM. |

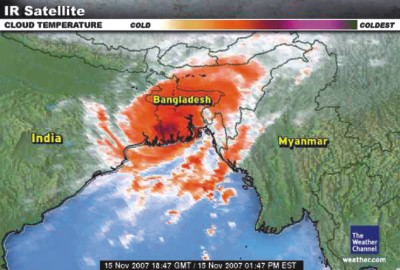

It doesn't seem too long ago that the merciless floods destroyed the lives and livelihoods of hundreds of the poorest in the North. Within only three months while the recovery process was still going on and people were trying to get their lives back together, nature unleashed its wrath with fiercer intensity and rage. In a matter of only a couple of hours, cyclone Sidr, a category 4 storm, said to be more fierce than Hurricane Katrina, left a trail of death and destruction of unbelievable proportions. 23,000 acres of crops completely wiped out; 10,000 people believed to be dead; nearly 9 lakh families affected to various extents; and nearly two and a half lakh domestic animals eradicated.

And that's just the official figure. The actual death toll is hard to estimate as many bodies have been washed away by the sea and rescue efforts are proving difficult in the many hard to reach places. But statistics cannot do justice to the actual human suffering caused on that fateful night of November 15. With wind speeds up to 240km/h (150mph) and a tidal surge of up to 20 feet high at some places everything in the path of Sidr from the Sundarbans, Barguna, Mongla port, Khulna, Bhola and Barisal was flattened to the ground. Millions of people are homeless, robbed of every possession they ever owned, if they are lucky to be alive that is. Although Dhaka was not in the direct path of the cyclone, the city dwellers felt the

power of the storm as windows rattled violently, trees swayed menacingly, the ominous sound of the wind kept everyone awake throughout the night. The whole country immersed into complete darkness as the national grid failed twice as a result of the storm and power was not restored in more than 24 hours.

Everywhere in the affected areas, the stories are chillingly similar, like 60-year-old Kadam Ali Hawladar from Chandramohon in Barisal who was found crying helplessly after losing all his family members and his entire livelihood. The reports of the scale of damage coming in every day seem almost too horrific to be true. But they are. The island of Dublar Char was the first hit. There is nothing but debris all over the island which once was a fisherman's paradise. Many people there in a desperate attempt tried to hide under upturned boats. Nothing helped. The power of the tidal surge was too strong. Bodies were found hanging from trees all around.

The wrath of Sidr has left hundreds of thousands of people homeless and without hope. PHOTO: SHAFIQ ALAM.

The Sundarban forest, the pride of the country with its sal forests and valuable wildlife - devastated beyond imagination. As much as one-fourth of the forest area has been completely damaged by Sidr. The exact loss of flora and fauna is yet to be calculated.

The whole of Bhola district is also very badly hit. Although the cyclone was more powerful than the one that hit in 1970, because of the forests the devastation was a little less than it could have been which really isn't saying much. 32 people died and most of the deaths unfortunately occurred when residents tried to run to shelters after the storm started. As the wind started picking up speed hundreds of trees started falling and trapping humans under their bark. Almost half of the crops were destroyed. Amon, the standing crop would have been mature enough to be harvested in only a couple of week's time, now it has been destroyed. The residents of the area are in dire need of food and drinking water, or the correspondents there say, there will be more diseases and more deaths.

In Barguna people's woes are indefinable. Thousands of the poorest of the poor people are sleeping under the open sky. According to correspondents there is no food or drinking water at all and the relief is not enough for everyone. 60% of the tin and kacha houses are destroyed and domestic animals are almost non-existent. Communication has not been fully restored to the area yet. 94200 hectares of amon crops, 675 hectares of rabi, 17850 hectares of kheshari daal and 58 hectares of betel leaf fields were completely destroyed.

In Barisal, the floods a few months ago, had already done a lot of damage to the crops already. For a district that is largely dependent on its crops the sufferings of the people who have luckily survived is unimaginable. Almost 100% of the amon crops has been destroyed. Many have died from tree falls. Most of the farmers there had taken loans from various NGOs. Now the source of income from which they were repaying the loans has disappeared. That is a double blow to these wretchedly poor people. The vacant looks of utter despair are everywhere. They don't know how they would start rebuilding their lives and returning their loans. In Barisal, the floods a few months ago, had already done a lot of damage to the crops already. For a district that is largely dependent on its crops the sufferings of the people who have luckily survived is unimaginable. Almost 100% of the amon crops has been destroyed. Many have died from tree falls. Most of the farmers there had taken loans from various NGOs. Now the source of income from which they were repaying the loans has disappeared. That is a double blow to these wretchedly poor people. The vacant looks of utter despair are everywhere. They don't know how they would start rebuilding their lives and returning their loans.

The Bhola cyclone of 1970 took the lives of 5 lakh people. Cyclone Gorky in 1991 killed at least 138,000 people and left as many as 10 million homeless. It's been exactly 37 years since the Bhola cyclone. The storm warnings were announced throughout the country from Tuesday, November 13. The path of the storm was followed with exact precision. Despite all this, the devastation was merciless; the loss of lives, crops and animals terrifyingly high. For a country like Bangladesh it seems the poor never get a break, the moment they start dreaming of a better future, fate stops them dead on their tracks. The geographical position of the country and the impact of global warming ensure that natural disasters will be a part of our lives forever. But could the severity of the impact have been avoided? Could the loss of lives have been minimised? Could something have been done to save the lives of the animals?

On a larger scale of things, Naeem Wahara, the Emergency Focal Person of Save the Children UK, and the Convener of Disaster Forum thinks that a strong, accountable and responsible government is an absolute necessity to better handle disaster. “It's true that the loss was minimised in a big way because of the signalling but the cyclone shelters are not exactly a proper solution,” says Wahara, “it's not really practical to ask people to leave their houses and go somewhere else for shelter for an indefinite period of time. If you ask someone from Dhanmondi to take shelter in Gulshan they won't do that. People have the right to live in proper houses.”

“A danger signal number 10 was given 36 hours before the cyclone actually hit,” says Wahara, “but according to the Standing Orders on Disaster [brought out in August 1999 by the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief Disaster Management Bureau] the signal should be given only 10 hours before the actual hit. The common people thought that it was like the tsunami warning and did not take heed of it.”

The amon crops would have been harvested in a couple of weeks' time. Almost all of it, in and around the path of the storm, was destroyed. PHOTO: FOCUS BANGLA.

Wahara believes that the local governments should be better equipped to handle such disasters. “The authorities are looking more at damage assessment rather than need assessment,” he says, “water is the greatest need of the day. The authorities should think of long term food assistance and reconstruction work.”

Dr Ainun Nishat, Country Representative of IUCN, the World Conservation Union of Bangladesh, and Professor of Water Resources Engineering of BUET also criticises the signalling system and says, “in the 'Standing Orders on Disaster' the government has laid out clearly what needs to be done when a disaster comes which gives a clear idea about who will do what before a disaster at the national, district, thana and union level.”

The Standing Order defines what should be done at the normal phase, for example, when building an embankment, at the alert and warning phase, the disaster phase and recovery phase. “Every ministry's responsibilities are outlined here,” says Nishat, “everything is documented.”

Although he thinks that there is a lot of scope for improvement especially being vague at times, he adds, “we are not operating in a vacuum.”

Nishat also criticises the signalling system. Signal I indicates 'squally weather in the distance sea where storm may form'; signal II indicates 'a storm has formed in the distant sea'; signal III indicates that, 'the port is threatened by squally weather'; signal IV indicates that 'the port is threatened by a storm but it does not appear that the danger is as yet sufficiently great to justify extreme precautionary measures.' The signals V, VI and VII are the same in terms of speed of the wind but indicate 'that the port will experience severe weather from a storm of slight or moderate intensity that is expected to cross the coast' from three different directions according to the numbers. Signals VIII, IX, X also are essentially the same in terms of speed (more than 54m/hr (88km/hr).

A total sense of helplessness. Lives and livelihoods destroyed forever. PHOTO: SHAFIQ ALAM

“This rule is perfectly alright but the common people were a bit confused about how it jumped from number IV to number X at one go,” says Nishat, “generally people think in terms of a sequence. This process is very old and was used during the British period to give warnings to the captains of the ships. This system needs to be changed.”

Nishat also points out that reports from various sources indicate that the warning was given too early. “Some people went back when the rains started,” he says, “according to village folklore if it's raining it means that the cyclone has passed.”

He also points out that although in places like Patharghata the storm did not get inside the five-metre-high protective embankments there are thousands of people who live outside the protected area who are basically the landless people. “Thousands of people died there.”

“Our main problem is that we do not have any database on people unlike in places like Europe where one has to be registered with the police station,” says Nishat, “so it's very difficult to assess the exact death toll.”

Dublar Char: Sidr destroyed everything in its path. PHOTO: SYED ZAKIR HOSSAIN.

Nishat also argues that if the gap between two disasters is large people tend to be unmindful of the danger and there is not enough preparedness. “So many warnings are aired in the coastal areas all the time that many people don't take it seriously,” says Nishat, “in fact Cox's Bazar had a warning no9 and there were strong winds but the storm surge wasn't there.”

Nishat also believes that every neighbourhood should have at least one or two buildings which could work as a shelter. “Any public building, for example belonging to the union parishad or a primary school should be used as a cyclone shelter,” he says, “making one exclusively as a cyclone shelter doesn't work because it stays unused for 350 days a year. The approach road for that building also has to be good.”

|

Under the open sky. Tin sheds were blown away by the ferocity of

the storm. PHOTO: AFP |

An old Banyan tree fell inside the premises of BSMMU during the storm and trapped a man for four hours. PHOTO: AMRAN HOSSAIN. |

Relief work is going on all over the country. Donations are coming from home and abroad. Thanks to the extensive media coverage the huge expatriate community is chipping in generously with what they can. But nothing can replace the lives of the people lost. The lives of the families who have lost loved ones have changed forever. Experts have been stressing on the need for more comprehensive and methodical measures to prepare for disaster management since the cyclone in 1991. Most of all the whole community must work together to help the affected to get back on their feet. Despite the overwhelming destruction and loss of life in the hard-hit areas, parties at posh hotels in Dhaka were not called off the day after the disaster. It goes to show how far removed the privileged sections of society are from the miseries of their compatriots, something that is appalling and reprehensible.

They did not stand a chance for survival. Although precautionary measures were taken for humans, no thought was given to the animals. PHOTO: AFP.

Every time a disaster comes it's the poorest of the poor that are hit the hardest. It's a wonder how they pick themselves up again and start their lives anew and the smiles come back on their faces. But their resilience must not be tested any further. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |