|

Book Review

Things fall apart

for farm family

Marcela Valdes

Michael Ondaatje must be a romantic optimist. In his novels, obsessives and traumatised loners, the kind of people sane souls avoid after a couple of dates, regularly manage to find deep, nourishing love. That doesn't mean they're good at holding on to it -- even optimism has its limits. But so much the better if the romance comes and goes. After all, the discovery and collapse of a rare love has made for some marvelous plots. Michael Ondaatje must be a romantic optimist. In his novels, obsessives and traumatised loners, the kind of people sane souls avoid after a couple of dates, regularly manage to find deep, nourishing love. That doesn't mean they're good at holding on to it -- even optimism has its limits. But so much the better if the romance comes and goes. After all, the discovery and collapse of a rare love has made for some marvelous plots.

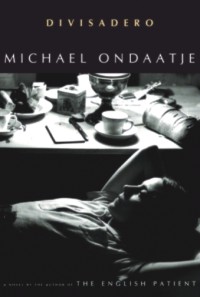

Ondaatje's most famous novel, 1992's "The English Patient," took just such a romance and revved it into high gear with details about Italy, Herodotus, desert research, bomb-disposal and the North African theater of World War II. His new novel, "Divisadero," adopts the same strategy, but set mostly at gambling tables in California and country towns in southern France, it's both seedier and more pastoral.

The novel opens on a farm near Petaluma, where three lonely children are raised by a tight-lipped widower. The farmer's wife died in the late 1960s while giving birth to Anna. Leaving the hospital after the event, the grieving man picks up an orphan baby named Claire and makes her Anna's sister. (As far as he's concerned, the hospital "owed him something.") Coop, a hired hand whose parents have been murdered, completes the trio.

A few years older than the sisters, Coop's the only available man for miles around. The sisters enter adolescence vying for his affection. At 16, Anna wins, shedding her clothes like so much rubbish on a rainy afternoon. The sweet comfort of teenage love doesn't last long. Anna's father soon discovers the affair, and his volcanic rage scatters the family. Coop flees to Lake Tahoe, where he transforms himself into a cardsharp to pay the bills. Anna hitchhikes to Bakersfield, and eventually becomes an academic living near Dému, France. Claire stays home with Pa to pick up the pieces, then moves to San Francisco and turns habit into vocation: she makes a living in the Office of the Public Defender, researching crimes.

"I was interested in the idea of a family that splinters," Ondaatje recently told Canada's Globe and Mail. "People who grow up in a very tight universe, and then something happens and they go out over the whole world." Such trajectories are common enough in this world of jet-propelled immigration, as Ondaatje understands viscerally. Born in Sri Lanka in 1943 to a Dutch father and a Ceylonese mother, he was forced to move across the globe to England when he was 10, in the wake of his parents' divorce. At 18, he crossed the world again, throwing over the life of an English schoolboy and moving to Canada, where he became a citizen and launched his literary career.

Ondaatje's novels are known for their collaged, nonlinear structures. "The perfect state for a novel," he once said, is "a cubist state" where several perspectives appear at once. "Divisadero" is no exception: Like his previous works, it plays whimsically with chronology and memory, with fantasy and historical fact. Such devices are now commonplace among literary novelists. In "Divisadero," however, Ondaatje also employs a more unusual tactic: half way through the book he suddenly drops its three main characters and swerves the story onto a different path. Two previously minor characters -- Lucien Segura, the early 20th century French poet whose life Anna is exhuming, and Rafael, the 53-year-old lover she's picked up in Dému -- step forward and dominate the story until its end.

In the hands of a less accomplished novelist, such an abrupt change in course might indicate exhaustion, or incompetence. Ondaatje, however, is no amateur. At 64, he's published nine books of poetry, five novels, a memoir, and a book about Walter Murch and the art of movie editing. (The film version of "The English Patient," which Murch edited, won nine Academy Awards.) Ondaatje's also won scores of highbrow shiny accolades , including a Booker Prize, a Giller Prize, and two of Canada's Governor General Awards. In April, he made the short list for the Man Booker International Prize, alongside Alice Munro, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, Margaret Atwood and Chinua Achebe.

What Ondaatje's after, his interview with the Globe and Mail reveals, is an "archaeology of character." That is, having followed three California characters from childhood into their 30s, showing how their personalities and behavior evolve, he spins around and takes two mature French characters in order to trace their histories back in time. It's a brilliant maneuver, one that proves all the more interesting because Lucien and Rafael's story -- which encompasses World War I -- proves more engrossing and touching than the story of Anna, Claire and Coop.

Anna and Claire are both too passive, too abstract, to make convincing characters. The sisters' loving, competitive relationship, so rich with potential conflict, is never really dramatized. All their major actions revolve around men. Chauvinism isn't the problem. Ondaatje deploys several fantastic female characters later in the book. The novel's opening chapters, however, are fogged with a vague sentimentality. Telling details are consistently blurred.

Ondaatje makes several references to Coop's "brown" skin, for example, without ever indicating whether he's Latino, Asian, African American, or just tanned from hard work. Coop does spring into focus when he reaches the casinos in Tahoe. But Claire and Anna never quite recover from "Divisadero's" air-brushed beginning. Their outlines are permanently soft.

Misty abstraction is always the danger of lyrical imagination, the tendency to see characters as romantic archetypes -- the lonely girl, the angry father, the poor brown boy -- rather than as precise, rough-edged people. Ondaatje's success as a novelist is due, in large part, to his consistent ability to avoid that pitfall. In "Divisadero," he briefly stumbles in. Then he finds his feet again.

This review first appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007

|