| Cover Story

A Place to Call Home

A young girl writes a poem where she asks a simple question -- one which no one can answer. She asks, “Who am I?” Her forefathers were born in India, they immigrated to Pakistan, she was born in Bangladesh. India has given up on them a long time back, Bangladesh will not accept them as the children of the land and Pakistan will not take them back. She says that she has many names 'Bihari', 'Maura', 'Muhajir', 'Non-Bangalee', 'Marwari', 'Urdu-speaker', 'Refugee', and 'Stranded Pakistani'. But she only wants one: human. This is the state of being of the 1.6 lakh camp-based Urdu-speaking community in Bangladesh.

Hana Shams Ahmed

Zubeida was born in the Mohammadpur Geneva Camp about 20 years ago. she got married last year, and her in-laws formally brought her to their home in another part of Geneva Camp. Their home is an 8 feet by 8 feet room where Zubeida shares a bed with her husband and ailing mother-in-law. Her brother and sister-in-law sleep on the floor of the same room with their two-year-old child. Her husband works in a barber's saloon and makes just enough to make ends meet. But they are unable to move out of their little room and live elsewhere. Zubeida's husband will not get work anywhere else. Zubeida herself was unable to study beyond 4th grade. Her parents could not afford the Tk 150 monthly school fees. Zubeida's family were packed into one of the 116 camps all over Bangladesh right after the Liberation War. The plan was to eventually send them to Pakistan. That was thirty six years ago.

After the partition of India in 1947, faced with large-scale communal riots on both sides of the border, a few hundred thousand Muslims from Bihar, Kolkata, Uttar Pradesh, Maddhya Pradesh and as far away as Hyderabad came to the then East Pakistan. All India Muslim League Chief Muhammad Ali Jinnah promised them that Pakistan would be 'a safe haven for all Muslims'. As is typical of people migrating from a common locality, 'Biharis' lived in separate clusters from the Bangalis. Their communities were concentrated in areas in Mohammadpur, Mirpur, Khulna, Chittagong and Santahar. Bangali animosity towards Biharis started growing in the 1960s due to the perception that the Pakistan government preferred to give Biharis better jobs. By 1971, there were about 15 lakh (according to RMMRU) non-Bangalis living in East Pakistan. The West Pakistanis and Biharis enjoyed special privileges and when Sheikh Mujib declared war in 1971 for a free Bangladesh, the Biharis were in a dilemma. They had suffered through terrible communal riots in 1947 for the idea of the state of Pakistan, and they had antipathy and deep suspicion towards the state of India. Believing the Pakistan army's propaganda that Mujib was 'plotting with the Indians to break up Pakistan', their sympathies naturally went against the Bangali liberation war. The Pakistan army exploited this weakness to recruit Biharis to join the Rajakar death squads. Not all Biharis joined, but those that did not remained silent spectators of the conflict. They did not join the refugees crossing the borders, or take up arms against the Army.

Without a citizenship they are being deprived of education and the prospects of getting a job in the future.

With the surrender of the Pakistan Army, it was the Biharis who were now suddenly stranded in a devastated country looking for compensation and redress. International Community for Red Cross (ICRC) made a list of the Biharis living in the newly formed Bangladesh and asked them whether they wanted to stay there or go to Pakistan. All the Biharis stated their desire to go to Pakistan for safety. And so the ICRC registered nearly 540,000 of the surviving Urdu-speaking Pakistanis who wanted to be repatriated to Pakistan and built camps for their temporary security. According to the US Dept. of State country report on Bangladesh, the stranded Pakistanis turned down the offer of Bangladesh citizenship and instead raised Pakistani flags in their camps, expressing their desire for repatriation to Pakistan. As a follow-up of the Simla pact of July 1972, a tripartite agreement was concluded in August 1973 between Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. As per the agreement, about 2.5 lakh Bangali prisoners were airlifted from Pakistan to Bangladesh and the stranded Urdu-speakers in Bangladesh were to be repatriated to Pakistan. In 1974, 1.2 lakh stranded Pakistanis were airlifted to Pakistan. By 1993, 17,8069 Urdu-speakers were repatriated to Pakistan under government initiatives. Others went on their own initiatives. According to latest UNHCR reports, there are around 1.6 lakh Urdu-speakers living in 116 camps in 14 districts of the country. But 36 years have passed by and 70% of the Urdu-speakers were born in Bangladesh after the war.

Conditions inside the camps are inhuman |

Twenty-eight-year-old Ahmed Hussain does karchupi work on saris inside the camp. Many of the Urdu-speakers have taken up handicrafts as their profession and their one-roomed homes are turned into their work place during the day. Ahmed works with four others in a room for five hours on a sari. He has been doing this work for 18 years. “I don't want to go Pakistan,” he says, “I have my work here and I enjoy it. It is a little problem to live in such a congested room but otherwise I'm really happy the way I am.” Ahmed earns Tk 500 a week with this work. Ahmed's 24-year-old co-worker Mir Jafar says that most Bangalis are nice to them. “Some Bangali people hurl abuses at us and call us 'mauras' but most Bangalis are not like that.”

According to Tanvir Mokammel, director of Shopno Bhumi (The Promised Land), a documentary on the plight of the Urdu-speaking community, most of the young generation of Biharis want Bangladeshi citizenship. “Unless you have citizenship rights, it is very difficult to get a job or venture in economic activities,” says Mokammel, “besides, a section of the leadership of the community discouraged them to go out and mainstream themselves as the illusion to migrate to Pakistan was kept alive.”

Mokammel says that he understands the animosity of the general Bangladeshis towards the Urdu-speaking community but adds, “What is happening to this community now is sheer insensitivity and negligence by the concerned governments and international bodies”.

For Khalid Hussain, President of AYGUSC (Association of Young Generation of Urdu Speaking Community) and Assistant Co-ordinator of Al Falah Bangladesh the most important requirement for the camp-dwellers is to get the National ID Card. “In our research (carried out by Al Falah Bangladesh in Dhaka, Mymensingh, Khulna and Faridpur) we have found that 70% of the people want to stay in Bangladesh, 17% want to go back to Pakistan and the others are not decided,” says Khalid, “Al Falah Bangladesh, AYGUSC and Shamsul Haque Foundation from Faridpur together submitted a memorandum where we pointed out that we fulfil all the requirements of the Citizenship Act of Bangladesh made in the Constitution and we should be registered as voters and we should be able to get our ID cards.”

The High Court in 2003 declared that 10 Urdu-speakers who filed a case and those living in all the camps around the country were citizens of Bangladesh. It was the first time that some Urdu-speaking Biharis have been recognised as Bangladeshi nationals. But the law ministry held back the order.

“I agree that our forefathers may have collaborated with the Pakistan army at that time but what about the persons who were not involved and the ones born after 1971, their rights are also very important,” says Khalid, “They are Bangladeshis by birth, this fact cannot be ignored, these people cannot be deprived of their fundamental rights. There are some politicians with anti-Bihari mentality who are not letting this happen.”

|

Khalid Hussain has been fighting for the fundamental rights of

the Urdu-speaking community for years. |

Ahmed Ilias, Writer and Executive

Director of Al Falah Bangladesh. |

The education rate at the camps is very low and Khalid blames the suspended position of the Urdu-speakers for this. “The government schools don't even take our children, they say that the government money is allocated for the citizens of Bangladesh only and we, as stranded Pakistanis, don't have any right on it.”

Khalid talks about a case in Khulna where a man passed his Masters exams and applied for a job at the forest department. “He qualified in the written and viva exams,” says Khalid, “but after investigations revealed that he lived in the camp, his government job was cancelled. He points out that if the National ID cards are not provided to them rickshaw-pullers won't get licenses and they will be deprived of all 19 facilities that come along with it. “Our livelihoods will be at stake.”

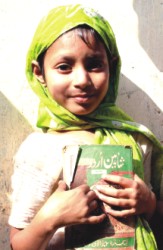

Her mother tongue is Urdu but her country of birth is Bangladesh.

But what is her identity? |

Abdul Jabbar Khan, President of SPGRC (Stranded Pakistanis General Repatriation Committee), or better known to be the camp office, openly admits to supporting the cause of the Pakistan Army but says, “You call us Razakars, but how many of us have actually physically taken part in the process. We supported Pakistan with our mouth only, but what about [Motiur Rahman] Nizami and Abdur Rahman Biswas who were even bigger collaborators than me. Why did this discrimination take place in my case? They were made ministers and given a big house and big car by the state but, my citizenship was taken away from me and I became a refugee and was locked away into this camp.”

Jabbar is not completely reassured by the voting rights and the ID Card solution proposed by young people like Khalid. “Some in the camp are asking us to become voters but the government that is now in power is not the elected government,” says Jabbar, “what if the new government comes and says they don't agree to all this, then where will we go?”

Jabbar like many from the pre-71 generation think they would be safer in Pakistan because of their involvement (physical or otherwise) with the Pakistan Army against the Bangladeshis. “Nawaz Sharif assured us that 3000 families would be sent to Pakistan in the first phase of repatriation but so far only 318 people have been taken to Pakistan ever since then. We are hoping that the new government of Pakistan under Nawaz Sharif's leadership might change our situation.”

Writer and Executive Director of Al Falah Bangladesh points out that the Bangladesh government has divided the Urdu-speaking community into two parts -- those who live inside the camps and those who live outside the camps.

Dr. CR Abrar says that the identity of the people should be made clear to them. |

“The main problem is with those who are living inside the camps, the government is not doing anything to rehabilitate them.” He points out that those who live outside the camps enjoy all the facilities of a Bangladeshi citizen. “I live outside the camp, I am a voter, I have an ID card, a Bangladeshi passport and a bank account and I can go abroad,” says Ilias, “there is no discrimination for us. We are as equal as all other Bangladeshis.”

Groups like SPGRC, Ilias points out, are taking advantage of the lack of government control. “They have a vested interest in this camp,” says Ilias, “if the camp exists, they will have this leadership. They have been planted with a fear that if they get citizenship they will be evicted from the camp. No one actually likes living in these camps but if they have the option that they can work and get education, they can get training and become skilled.”

Ilias thinks it is essential that the government solve the problem of their citizenship as soon as possible. “The government doesn't understand that if these people start working, they will become assets for the country and will only contribute to the national economy. Left like this, they will only become a social problem.”

70-year-old Osman Gani worked as a driver for the Pakistan Army in 1971. He owns up to 'taking up

President of SPGRC, Abdul Jabbar Khan |

arms' against the Bangalis but points out that his brother was shot in front of him by the Bangalis and he lost a lot of near and dear ones during that time. “I think its time to forgive,” he says, “fights can happen between brothers and even if your brother does something wrong are you going to get rid of him?”

40-year-old Khairunnesa who does handicraft to eke out a living says that she is tired of the journalists and NGO workers coming in and questioning them about their condition. “We didn't come here to go to West Pakistan. We want to become Bangladeshi; the people here have to accept us. The government has to do something about our situation or just kill us all with a firing squad.”

The tale of these people's lives is miserable. Families have grown since 1971 but they were left to make their lives in this one small room. Three generations of people live in this single room. Every morning people have to stand in a queue for hours to use the common bathrooms -- whether it's a pregnant woman or a fragile old man they will have to wait their turn to use the bathroom. Hygiene in and around the camp is almost non-existent. But for the sake of argument the slum-dwellers all over the country also live in very similar conditions so why should the plight of the camp-dwellers get priority?

Like everyone living in the camps, Zubeida (left) lives with three generations in the same room.

Dr C R Abrar, Professor at Department of International Relations of Dhaka University and Co-ordinator of RMRRU (Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit) says there's a major difference between the two groups. “The difference is that these people's identity has not been made clear and this is the one group of people for whom the state and NGOs have over the years shown complete apathy towards.”

Families have grown since 1971 but they had to make do with living in a single room. |

Abrar talks about a single incident which explains in a nutshell why this group deserves attention. A child born of Urdu-speaking parents was taken to an orphanage after both her parents died. When the orphanage authorities wanted a certificate from the local commissioner the commissioner refused to give it because she was a 'Bihari'.

Abrar says that the general impression that these people are getting all the utilities for free is not true at all. “The government may not be getting the money but there are rent-seekers who are making money out of this,” he says, “without trying to stereotype there are chances that criminality from these areas will increase as a result of this if we don't address these issues.”

Born after the war, these young people identify themselves as Bangladeshis and do not want to go to Pakistan. |

Pointing out that the High Court has already declared that they are Bangladeshi nationals Abrar says that the point that they opted to go back to Pakistan [in 1971] in the ICRC form has no legal validity. “In a country which has a large Diaspora population, where many people have dual citizenship and where hundreds of thousands of people apply for diversity visas every year, how do you ascertain whose loyalty is where,” he adds.

Abrar thinks it is very distressing that this community is made a scapegoat for the atrocities committed in 1971. “Whoever has committed the atrocities should be tried for their crimes, irrespective of whether they are Bangali or Bihari.”

So is this an internal matter or does the Pakistan government have some responsibilities for their rehabilitation? “Pakistan has a moral responsibility,” says Abrar, “except for Benazir Bhutto's government, right from Zulfiqar Bhutto to Parvez Musharraf subsequent heads of state said that they are going to take these people to Pakistan for the sake of the Islamic solidarity. In the end all these hopes worked against the anchoring of these people here and the term 'stranded Pakistanis' came about.”

Because of the half-hearted repatriation process hundreds of families have been divided between Bangladesh and Pakistan. There is a father who cannot attend his only daughter's wedding and there is a wife who cannot attend her husband's funeral. But the new generation who were born after the war and comprise the biggest chunk of camp-dwellers don't have any affiliations with either India or Pakistan. They were born in this country and identify themselves as Bangladeshis. Unfortunately the state is reluctant to accept them as such. It's a very complex issue because a lot of ambivalence from the majority population that is skeptical about these people's loyalty to the country they want to be citizens of. But the inhuman conditions they are living in and the subsequent effect it is bound to have on the society as a whole makes it imperative to resolve this painful issue.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008

|