|

Book Review

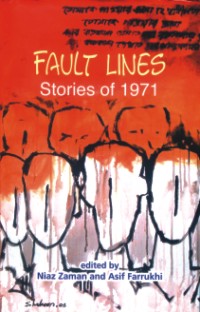

Fault Lines

Rezwan Ali

“Fault Lines,” was released at the Bengal Gallery on the 20th of March, 2008. It is a collection of short stories in English, both non-fiction and fiction, relating to Bangladesh's independence war. Countless books, poems, prose, etc. stemming from the sentiments of those who were there have been published, as well as numerous writings by writers too young to have experienced 1971 themselves but have used it as a source of inspiration. What makes, “Fault Lines,” different from these prior books, anthologies and such is that it contains stories from both ends of the spectrum. It is an assemblage of stories written by writers from Bangladesh and Pakistan. Most of the stories were originally written in either Bangla or Urdu and later translated into English. Well-known writer and academic Dr. Niaz Zaman, and Asif Farrukhi, a Pakistani writer renowned for his translations of English literature as well as various languages from the subcontinent, edited the book. “Fault Lines,” was released at the Bengal Gallery on the 20th of March, 2008. It is a collection of short stories in English, both non-fiction and fiction, relating to Bangladesh's independence war. Countless books, poems, prose, etc. stemming from the sentiments of those who were there have been published, as well as numerous writings by writers too young to have experienced 1971 themselves but have used it as a source of inspiration. What makes, “Fault Lines,” different from these prior books, anthologies and such is that it contains stories from both ends of the spectrum. It is an assemblage of stories written by writers from Bangladesh and Pakistan. Most of the stories were originally written in either Bangla or Urdu and later translated into English. Well-known writer and academic Dr. Niaz Zaman, and Asif Farrukhi, a Pakistani writer renowned for his translations of English literature as well as various languages from the subcontinent, edited the book.

At the book release event, Dr. Zaman ended her address with an amusing remark about how Dr. Zaman and Mr. Farrukhi, “got along because of the internet.” Saying, face to face the two probably would have argued too much to compile this collection. The two editors acknowledge that they hold differing opinions about what happened in Bangladesh in 1971, but are in agreement that these stories must be told. Here is a selection of stories from the book that were especially poignant.

Masud Mufti's, “Sleep,” was originally written in Urdu. It is essentially a modernised adaptation of the, “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” folk tale. A Pakistani man, repeatedly bothered by youngsters who yell, “Say Joy Bangla,” into his windows night after night finally gives in. But fate would have it that one night his half-asleep mutterings of, “Joy Bangla,” result in dire consequences.

Humayun Ahmed's, “Nineteen Seventy-One,” was originally written in Bangla. It is an engaging story with some very colourful characters. Its main character is Aziz Master. He is belittled by his own family for his cowardice and decides to invalidate their accusations. Unwilling to divulge the whereabouts of his family to the Pakistani army upon questioning, he claims that he is not yet married at the age of forty. The Pakistani army troops order him to, “show his equipment,” in an effort to humiliate him. But Aziz Master has the last laugh as he shocks the troops with his antics and the troops end up marching away leaving their self-respect behind.

Tariq Rahman's, “Bingo,” is another story written by a Pakistani. It is told from the point of view of an officer in the Pakistani military. Initially, the reader finds the officer to be an overzealous and hateful person due to his consistent insults to the Bangladeshis, or, “Bingos,” as he calls them. He seems to regard the Bangladeshi people as subhuman. Tajassur is the main character, another officer in the Punjab military. His peaceful, calm demeanour is mistaken for weakness by many of his fellow troops. As the company advances into then-East Pakistan a profound change occurs within the Pakistani officer's heart as he is kidnapped by freedom fighters, and then helped to escape by his, “Bingo,” Tajassur. Tajassur takes the officer to his family home to hide him there, the officer is taken aback at the family's non-concern that he is Pakistani. This story shows the basic humanity inherent in all persons. Whether or not we choose to accept it is obviously one's own choice, but upon reading stories such as Rahman's, “Bingo,” it is certainly hard to dispel its existence. This is a beautiful story of self-redemption, but like so many stories about 1971, it ends with stinging calamity.

Shaheen Akhtar's, “She Knew the Use of Powdered Pepper,” is another Bangladeshi contribution to the book. Akhtar's descriptions of throwing her packets of ground pepper and the ensuing clouds of red dust are adeptly written. The reader could easily find his or her own eyes burning in an envisaged escape with the main character. The story truly takes the reader back in time to those fateful days. Akhtar's tale is one of stoic courage. She was in the lion's den, so to speak, but always remained one step ahead of her captors. A skilled marksman with her packets of pepper, as the story ends, we also find out that she can precisely aim more than just a packet of pepper.

Gholam Mohammad's, “The Travellers,” another contribution from Pakistan, is especially remarkable. He writes from the point of view of a Bangladeshi villager. His story contained an air of hyper reality as a group of villagers recount being forced to kill their own families out of guilt. They despair over the dark night into which their sons have disappeared. That dark night is both a literal expression as well as a metaphor for the ubiquitous horrors the villagers are facing. The story's grave mood changes as the elder villagers are hopeful for their sons' return, “bringing fresh rays of morning light,” to their seemingly eternal night.

While the stories contained within are diverse and emote a plethora of memories about the war, the book contains numerous grammatical errors. From the first page though the last the errors are consistent. Oftentimes tense changes abruptly and some stories lack a steady stance and metre. These typographical mistakes don't take away from the essence of the stories in the anthology, but give the book an amateurish feel.

“Fault Lines,” contains many stories which needed to be told. Seeing as the majority of the population was not alive or old enough to have actively participated in the fight for freedom. It is an interesting book, as we get glimpses into the minds and hearts of our “oppressors.” Hopefully this book will help to lessen some of the mutual misunderstandings about 1971. It gives a human face to those whom many consider either oppressors or traitors and nothing more, which can only be a step in the right direction.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008

|