| Cover Story

A Purist's Journey

Safiuddin Ahmed |

Aasha Mehreen Amin

He is one of the founders of the modern art movement of Bangladesh, and one of the great masters of our art history. Reserved, self-effacing and sometimes seen as reclusive, he has remained unmoved by his own fame which has come despite his constant efforts to remain far away from the limelight. Safiuddin Ahmed has just celebrated his 86th birthday and conceded for the first time in his homeland, to have a solo exhibition. It is merely a glimpse of what this remarkable artist has accomplished, perfecting the modern techniques of art while remaining true to his sensibilities and roots. Shunning publicity, abhorring self-promotion and refusing to see art as a product, the artist has tenaciously guarded his principles while creating a spectacular treasury of work. Yet it is his personality and way of seeing life that has been continuously reflected in his work, which he has carried out with uncompromising dedication and love.

'Composition' (Engraving Aquatint, 1958)

To try to describe the range of work that he has done is like trying to study the ocean that holds limitless beings and elements, colures, shapes, textures and mysteries at every layer of its existence. He is an artist who has perfected everything he has touched, from romantic oils of landscape and nature to unbelievably detailed engravings, to intricate etchings and striking drawings, every form, every medium, has been experimented with and taken to its finest level under his Midas hands.

Safiuddin's formal training in art began at Calcutta Government School of Art in 1936, where he started making waves with his immaculate, realistic oil paintings for which he won his first prize, but soon began to attract attention for his expertise in engraving, dry point and etching. His teachers included stalwarts like Mukul Dey, Abdul Moyeen and Romen Chakravarty and they constantly inspired the budding artist, encouraging him to find his own style and technique. At the time (not unlike the present), pursuing studies in

'Thrashing paddy' (Oil, 1952) |

art, let alone considering it a profession, was frowned upon by conservative Muslim families. Abdul Moyeen persuaded Safiuddin's guardians to allow him to continue studying art, he also gave the young man valuable pointers in the art of print making and proved to be a saviour during some of Safiuddin's darkest hours. Romen Chakravarty also helped him to master this art form. For Safiuddin, Calcutta was very much his hometown, being born in Bhabanipur on June 23, 1922. Three generations of his family had lived there. His father and grandfather were devout Muslims but were far from being communal; they respected all religions. Thus Safiuddin grew up in a fairly liberal environment that valued culture. Safiuddin's sister learnt music and he himself learnt to play the sitar, apart from being quite a sports enthusiast. But Safiuddin lost his father Matinuddin Ahmed at age six and so was destined to grow up in the absence of a parent. He was thus very close to his mother who supported him in all his artistic endeavours. But the loss of his father was to have a deep impact on the artist from those early years, he grew up a little aloof from everything and his life became a disciplined journey that cut out any kind of excess or superfluity. This distancing from the immediate stimuli and sense of discipline can be detected in his work. Each piece, whether a painting, a wood carving, an etching or a drawing is circumscribed by a frame, it is detailed and filled out from inch to inch, there is nothing ambiguous or extraneous, everything is there for a reason. Even in his most intimate images, whether the anguished straining of fisherman towing their boats against the current or the arduous threshing of paddy by lean peasants amidst a glorious harvest, there is a distancing of the self from the object. This is accentuated in his drawings and etchings, which from a distance are hypnotic, geometric patterns but concealing within them, upon closer look, figures, faces and distinct emotions. They are not his own feelings, which he zealously keeps private, but those of others that he can sense and understand.

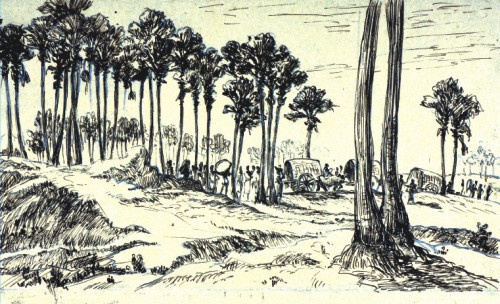

'One the way to the fair' (Wood Engraving, 1947)

Being a purist and nature lover, the young art student started to venture out of Calcutta ending up in Dumka where many Santal families lived. It was based on his visits to this serene area that gave rise to his Dumka series. These include his wood engravings of Santal women collecting water from the river, a Santal family on the way to a fair , oils depicting the tranquillity, simplicity and beauty of Santal life, the kind of simplicity that he has always strived and craved for.

He next delved into etching, some of which depicted the free and open landscape of

'In memory of `71' (Engraving, 1988) |

Shantiniketan. But it was his oils that first grabbed the attention of the art scene in Calcutta. His paintings of fishermen and peasants were outstanding in their detail and muted colouring and also conveyed the stoicism and strength of these people of the land. It was when he was offered a job as a teacher at the Calcutta Government Art School, that Safiuddin got his first brush with fame. He won the highest award at an exhibition patronised by the Maharaja of Dwarbhanga for his Dumka sketches. The previous year 1945 he had received the Academy President's gold medal for his painting titled 'Dove'. He won a couple of more awards in 1946. All this recognition got him a membership in India Fine Arts and craft society giving him more prominence. In 1947 his print work on Dumka, was displayed at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Musee d'Art Moderne et d'Art Contemporain) in Paris at an international exhibition where the work of Picasso was also exhibited.

The country, however, was about to undergo the greatest political upheavals in its history and the pre-partition days were filled with communal violence that deeply saddened and disillusioned the artist. Safiuddin decided to leave his beloved Calcutta and settle in Dhaka. He became an art teacher at the Collegiate School and later joined the Institute of Art which he helped Zainul Abedin, another great master, to establish. This new challenge to develop the institute from scratch, gave him the impetus he needed to resume his work. He became the head of the print media department. Thus Safiuddin became part of the second generation of pioneers of modern print media in India, his teachers being the first generation.

With his childhood and early adulthood spent in a big city like Calcutta and then resettling in Dhaka, another city, it is not surprising that Safiuddin's outlook and approach was very urban and modern which was reflected in his suave demeanour and appearance. He was tall and always simply but impeccably dressed, an impressive figure in the Institute. “As a person he has always been very sophisticated, subtle and restrained,” says Professor Azizul Huq, a close associate and friend who had been a teacher at the institute of Fine Arts for many years. “This restraint, neatness and pursuit of perfection is evident in his creative work”, explains Huq, now a professor of the Bangla department at Dhaka University. “His technique was contemporary but the themes he worked with were invariably rural.” Like the artists of his generation, he too was affected by his surroundings. In 1954, he witnessed a devastating flood that even submerged the areas around his house in Shamibagh in Old Dhaka. At the time Dhaka was sparsely urbanised and there were many open fields and forests. The artist now found himself in a setting, here people were used to the regular visits of floods. His work therefore depicted the overwhelming force of the floods, the loss of life and property, the suffering, the struggle of fishermen, themes that have recurred through-out the artist's creative journey, though manifested in different and novel forms.

After working for about ten years at the Institute he went to study, on his own expense, to the London Central School of Art. Here he was taught by Merlyn Evans who had been a student of the famous print maker William Hetter. Safiuddin learnt the latest techniques of print making, perfecting the methods of copper engraving and etching in aquatint. While he had already become an established artist before coming to London, it was this experience that gave his self-confidence an immense boost as he had now worked with the best in the field. From then onwards, there was no looking back for the artist and he continued to work independently, equally impervious to criticism or praise. He was still haunted by the memory of the 1954 floods and he made a number of copper engravings titled 'Flood' where he used precise strokes and swirling lines to recreate the power of the floods and man's struggle to survive through it.

'A bookstall in Paris' (Oil, 1960)

His first solo exhibition was held in 1959 at the new Vision Centre Art Gallery, London.

“But while his experience in London urged him to go on with his print work, he continued his oil paintings,” says Professor Huq. “Another media he experimented with was drawing. Usually a drawing or sketch is done to provide a basic draft before a painting in oil or a print. But for Safiuddin, a drawing would have to be a complete piece of art with perspective, tone, light and shade and so on.”

Throughout his artistic career Safiuddin has admired the works of many western artists such as Rembrandt and other European impressionists as well as Picasso, Henri Matisse, Ernest Ludwig Kitchener and Emile Nolde. At home he was impressed by the works of Mukul Dey, Binod Bihari, Nandalal Basu and Rabindranath Tagore.

'Dumka' (Dry point, 1945) |

Coming back home in 1959, Safiuddin felt more than ever, his attachment and fascination with his own land. But he did not believe in dwelling on the past, he avoided sentimentality and only focused on what was happening in the present. He was very much in touch with reality, it was the reality of the masses, an allusion to his left leanings. He also delved into experimentation with zeal and confidence, bringing constant innovation to his work. His obsession with perfection and sheer dedication inspired his students to develop an undying passion for art honed by a cultivated taste.

Although not directly involved in the politics of his time, Safiuddin has always been affected by the major political movements that he has been witness to. He had been closely involved in the cultural movement of the forties in Calcutta. In Dhaka he shared a house with Qamrul Hasan for a while in Hare Street where he met Professor Ajit Guha, a leftist and their house became a centre for cultural activities and literary discourse.

When Safiuddin came home from England, he found the country to be under a stifling, authoritarian regime and his frustration seeped into his first works which were prints in semi abstract style. He began to use the eye as a symbol to express human emotion. 'The Angry Fish' an etching in aquatint (1964) gives expression of the suppressed rage of a people being pushed against the wall; the intense look in the eye of the fish manifests this emotion. In later years the use of the eye as a symbol is used with greater intensity as in the engraving titled 'The Language Movement' (1987) and the 'In memory of 71' series where numerous eyes show the anguish, determination and endurance of the muktijodhas, ordinary men, women and children caught up in the liberation war. After the massacre of March 25, Safiuddin and his family- wife, two sons and daughter, stayed back in their Shamibagh house as they had no village home to escape to. At one point however, his wife and children went away to his sister-in law's house in Manikganj and Safiuddin remained all alone in the house with his dog. The days were filled with the terror of being picked up by the Pak Army any time and the horror of the atrocities all around; this is reflected in his drawings at the time which later became coloured

As a student in Calcutta Government School of Art. |

engravings. The colour blue became predominant in some of his oils that he did in the 1970s. Blue was used as the colour of subdued sadness although even that was never overstated. “His oils always show a minimisation of colour,” says Huq, there are no basic colours, the hues are always muted, the result of meticulous and perfect blending. It reflects the type of life that he has always led, there is nothing jarring or showy, everything is peaceful and in harmony.”

For Safiuddin art was a lot like music with its precise notes, nuances and scope for innovation while in keeping with the basic grammar. He avidly listened to eastern and western classical music and in the 1980s he decided to bring his experimentation to a newer level. His 'Sound of Water' is an experimentation with different kinds of media etching, engraving, soft ground and aquatint. Like an orchestra that has to blend the music of different instruments to create a perfect piece of music, this work is the coming together of different media. Thus Safiuddin has always strived to bring something new to art, moving away from conventional methods.

In the nineties, Safiuddin became enamoured by the colour black and this reflected in many of his drawings.

His commitment to perfection has meant that many of his works have taken a long time to complete, sometimes spanning a year or two which is why the number of works this great artist has created are not many compared to other artists of his calibre. Although he has taken part in innumerable group exhibitions at home and abroad, he has only held two solo exhibitions that includes the present one at Bengal Gallery.

According to family members, the artist has spent almost all his waking hours immersed in his work. "Right after breakfast he would go into his studio and work all throughout the day," says Ahmed Nazir, his second son who is also an artist. "In fact he would get visibly startled if we barged in unannounced or made too much noise in the house." During his work he requires total silence, refraining from even listening to music, one of the few things he likes to do besides artwork. The range of music he likes is huge, from Angurbala to Mozart to Rabindra Sangeet. He also likes to read books, but they are often books on art.

With Zainul Abedin, Aminul Islam, Hashem Khan and others at the Bangladesh art exhibition in New Delhi, India (1973)

As a father he has been loving but always a little aloof and far from being over protective. Being the son of such a great artist, it would be most natural that a son of Safiuddin's would follow in his footsteps. But Ahmed Nazir's entry into the art world was never prodded on by his father. It happened rather naturally although the artist admits with a twinkle in his eye, "I was naturally quite happy that my son was carrying on the family tradition." When he entered the Institute of Fine Arts that his father had help to create, Nazir was taught by Muhammad Kibria, another stalwart in the modern art movement of the country. He was being taught by the best but it was strange that at home his father, a master in the field, made it a point never to influence his son in any way. "At the time I was really irritated by his refusal to assess my work," says Nazir, " he would say you have a great teacher, go and ask him; but now I understand that he was doing this for my own good, so that I could develop independently and have my own style rather than be a shadow of his."

The artist, with his wife, Anjumanara Ahmed. |

Safiuddin therefore inculcated this kind of self-sufficiency in his children (two sons and a daughter) too for it was something that he considered to be most precious.

Being completely devoted to his art without reaping any financial benefits from it must surely have taken it's toll on the domestic front but the artist's family has always been very supportive of the life he chose to lead. “He was always working (with art) but this did not mean he neglected his household,” says the artist's wife, Anjumanara Ahmed. “He is an unbelievably good human being, very honest, soft-spoken, never raises his voice and always very courageous”, she adds.

Life came to a standstill one morning around two years ago when the artist was on his daily morning stroll around his Shamibagh compound. He stumbled against a brick fence and fell, breaking his kneecap. The accident has left him unable to walk and recently an intense pain in his spine has made him practically bed-ridden. “This has been a big blow to him,” says Nazir, “ being such a self-sufficient person, to be in this state of dependence and helplessness, not be able to work has been devastating and he often gets very depressed.”

In his room in an apartment in Dhanmandi that he has been shifted to get better medical attention, the artist lies in his bed most of the time. “It is really painful for me to not be able to walk around, but most of all not to be able to work,” says Safiuddin surprisingly clearly despite his ailments, “all I wonder is whether I will be able to draw again.” Yet even his latest exhibition, he has managed to give two works that he recently did while being propped up in his bed. With humility that is almost ludicrous in an artist of his stature he says, “You see, I had just reached the stage when I thought I had finally learnt something and then this accident happened.” Safiuddin, even after being regarded as one of the greatest artists of the subcontinent, is still the incorrigible perfectionist, never quite satisfied with his own work.

'Boat and Tree' (Charcoal and Crayon, 1966)

One of the most intriguing aspects of Safiuddin's personality and one that is often perceived with frustration from his admirers is his adamant refusal to sell his work. “Many people have criticised this and have even called him overly possessive of his work”, says Huq, “but to me it is a positive thing. He has always taken art as a passion; he is free of the pursuit of fame or financial gain. He has always lead a very simple life, one devoid of any kind of self-indulgence; he has always lived within his means and is content with very little.”

In the rare interviews that he has given Safiuddin has explained that he keeps his own work in order to see how he has progressed. His son Ahmed Nazir intends to preserve his father's precious works in a private gallery or museum. The idea certainly makes sense; the works of many of our great artists are lying in corners being eaten by dust mites. Like the expansive museums for artists such as Van Gogh or Picasso, we could have such galleries where such priceless work could be displayed and appreciated by everyone, provided of course that the necessary security measures are taken and restoration expertise is ensured. If that is what the artist has in mind, it will be the greatest gift an artist of his brilliance can give to the world.

Acknowledgement

Some of the information on the artist's life and work has been taken from the book 'Safiuddin Ahmed' by Mahmud Al Zaman published by Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy.

Photographs: Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts.

Limitless and Eternal

Nader Rahman

New experiences are often tough to deal with and generally the older one gets, the tougher they become. At the age of 86 one could forgive Safiuddin Ahmed for not trying anything new, for simply settling with what he had done his entire life; but seemingly that was not good enough for him, he had other plans. In a move that reverberated through the art scene in Bangladesh, the master decided to have his first ever solo exhibition in Bangladesh and with that announcement tongues went wagging. A man who generally shied away from the spotlight had finally stepped into it and produced only his second ever solo show, more than 49 years after his first. As the grand old man of Bangladeshi art his repertoire was wide and varied. From his mastery of oil painting to graphics, much was expected out of the exhibition and in the end he had yet another surprise for us.

Black Series-15 (Charcoal, 1994)

He chose to exhibit 86 of his hand picked drawings, thereby shutting out his best known forms of work. The move both surprised and intrigued the public, as he chose what many consider to be drafts as finished pieces. While that may have been what was heard around the water cooler, only those who saw the exhibition could actually exactly experience how breathtaking 70 years of his drawings could be.

The very first piece was his earliest, drawn before partition in 1945 it is titled “Views of Shantiniketan”. The simple ink drawing is small and complex with a number of people in the background walking with bullock carts. The lines are steady and intricate, which is all the more surprising as the paper is quite small at 12 by 20cm and there are no real hints as to where his future art would take him.

Black Series-14 (Charcoal, 1994)

Some of the most stunning and memorable work from the exhibition comes very early on in the exhibition with his 'Towing' and 'Fishing' drawings from 1950. The images conjure up what must have been futurist thoughts of the present way of life. The men towing have almost buckled under the pressure of their work as sweat drips off them, their lungis folded above the knee, a silent yet telltale song of backbreaking work. The images in brush and ink exhibit two decidedly different views of work in the fields. While 'Towing' is full of pain and angst, even the assorted shrubbery is dark and ominous as the two men in the picture could well represent existential life of Sisyphus. The analogy works in more ways than one as his representation of 'ploughing' through life is not one of optimism, but one of bleakness. A sort of bleakness only those who go through the rigors of manual labour can ever feel. 'Fishing' on the other hand is far more vibrant with not only increased movement representing the vibrancy. The water is subtly given a lively character, coupled with the birds in the background and the seemingly carefree fish, the scene is quite positive to say the least. The ink has been spread around less generously thus giving the drawing an open airy feeling, one which is often missing from his works.

A collection of nude study's from 1957 to '59 adds an interesting touch to the exhibition. A few are unremarkable while others really catch ones eye. 'Nude Study 1' is one such example, with it one can see how aptly the exhibition was titled 'The Limitless Luminosity of Lines'. While the figure in the drawing has turned away, Safiuddin has caught the boredom of the model beautifully. Leaning on one hand, while the other lay in her lap, he uses simple lines to convey the most candid of moments. Her straight back does not prevent her from leaning forward and with one foot folded beneath the other; it may well have been an outtake but feels like the real thing.

|

| Self-portrait (Pencil, 1960) |

'Labourers with a Fiddler on the Roof' (Brush and Ink, 1950) |

As his work evolved his style became more distinct and the drawings from the '60s emphasize that point. The charcoal and crayon 'Boat and Tree' from1966 is a type of image that most art galleries are full of now. A seemingly incandescent tree is placed beside collection of boats as Safiuddin tries to piece together Bangali culture in a time of turbulence. Testament to his influence on mainstream art, such images seem to be stock paintings of many an artist in modern Bangladesh. 'Cloth Merchant 1' from a year later shows just how different his work could get. In the drawing an almost faceless merchant is seated in front of his wares. The jackets in the background are suspended midair as they stand at attention from their respective hangers. They appear faded and stand out in the dark background almost spectre like. From the mid-seventies his work (drawings not particularly his paintings) became darker and more laboured as meshes of deep black and grey lines made up powerful images of sailboats and buffalos working the oil press. Even his 'Peanut Vendor 2' was not saved from the seemingly harsh lines that composed a work so mundane as this. The charcoal of his lines were stable yet frenzied.

Views of Santiniketan (Pen and Ink, 1945)

Two sunflowers from 1980 also catch one's attention as they appear to be genuinely influenced and harvested by late cubism. The charcoal and crayon black is well textured and the fractures within he drawings seem to hint at duality of some sort. Two stunning pieces from '87 titled 'Remembering Ekushey' 1 and 2 are symbolic masterpieces. A plethora of eyes look on as protests go on in the background. The at times chaotic lines also reveal the profile of transparent face bears witness to the horrors of that day. In very light lines protest signs can be seen raised in the, ghost like images of what our nation has been through.

Safiuddin seemingly always has an eye out for the problems of Bangladeshi society, choosing to draw what the struggles of our unheard of majority and thus floods play a vital part in his work. The few flood drawings he selected were about as complete and complex as drawings can get. The one from 1988 seems to mirror Picasso's Guernica in the layout as his '94 one is similar to the setup used European 18th century religious paintings. Yet they all are distinctly Bangladeshi, blank faces, without hope, the huddled masses waiting for salvation or at least respite. His work seems to breathe for the everyman.

Views of Santiniketan (Pen and Ink, 1945)

His monumental 'Black' series from '92 all the way to '94 spans over 15 canvases and produces astonishingly dark work with an eye out for detail. Numbers three and four standout charcoal, ink and watercolour are mixed to produce an almost lacquer like effect on a very dark canvas. The immaculate shading adds to his mastery, as black is transformed into a creature of the night, with shapes and sizes one has never seen before. It is the kind of effect one could get when wearing infrared night vision goggles through a dense forest in the still of the night. The creatures can be seen and the forest felt, and yet together the whole image still seems surreal.

Into the turn of the century and beyond his work has evolved even more, with an increased use of charcoal and crayon. His seemingly nimble fingers have not aged as he continues to texture his work beautifully and more expertly than before. Dark shades are spread out like the monsoon skyline and out of the darkness comes the many subtle shades of light. The complexity of his work is that the darkness and the light are symbiotic and yet their absence is what defines each other. His sole drawing from 2008, 'An Empty Chicken Coop' is the case in point. The fain lines of the chicken coop, eek out of the darkness of the canvas and even with the presence of light, we are inevitably alone and empty.

Fishing (Brush and Ink, 1950)

This exhibition by a Bangladeshi master is one to cherish, and given his age it could even be his last solo exhibition. It has taken him 49 years to get to his second; we are left wondering how many more till his third. With this exhibition he has proved his work to be limitless and eternal, as many people think he is as well. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |