| Remembrance

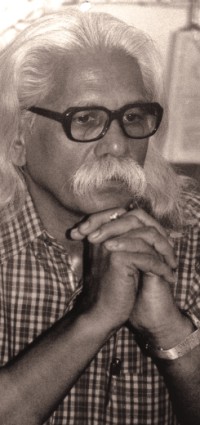

Samudra Gupta

A Poetic Voice against

Persecution and Injustice

Syed Naquib Muslim

Samudra Gupta ( SG), one of the distinguished poets of our country, died of cancer on July 19 in a hospital in Bangalore, India. For years together Samudra Gupta whose original name was Abdul Mannan Badsha remained incognito hiding his Muslim identity. But at the fag end of his life, he exposed his true identity in his last publication “Matha Hoye Geche Pakha Shudhu Urhe”. The jacket of the book gives out that Mohsin Ali was his father’s name and Robeya Ali his mother’s. Coming from Royganj of Sirajganj district, SG spent most of his time in the Dhaka city where he made himself visible and audible in various cultural forums. Samudra Gupta ( SG), one of the distinguished poets of our country, died of cancer on July 19 in a hospital in Bangalore, India. For years together Samudra Gupta whose original name was Abdul Mannan Badsha remained incognito hiding his Muslim identity. But at the fag end of his life, he exposed his true identity in his last publication “Matha Hoye Geche Pakha Shudhu Urhe”. The jacket of the book gives out that Mohsin Ali was his father’s name and Robeya Ali his mother’s. Coming from Royganj of Sirajganj district, SG spent most of his time in the Dhaka city where he made himself visible and audible in various cultural forums.

It was in 1973 when I became acquainted with SG at a friend’s house in the old part of Dhaka. A host of young poets assembled to spend an evening of poetry recitation. I was present as a member of the audience. We met not more than four times as my bureaucratic time and his literary time could be rarely reconciled. However, we met for the last time on March 28, 2008 at a prize-awarding function of Jatiya Lekhok Forum at the Public Library auditorium where I discovered him as the special guest and myself the chief guest.

In a country where many people struggle for meeting basic needs of life, poetry does not remain as a popular activity because most poets can hardly put bread on the table. Poetry is not a popular medium also because as W C Williams says, “It is difficult to get news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” Samudra Gupta knew about it but he still carried on his literary journey until his death. To him, poetry was a vehicle of registering protest against the unscrupulous actions of dishonest rulers. He lived in a society where greed and fraud abound, and integrity is considered by many as an impractical value.

SG led a life of austerity and always championed the cause of the poor and the downtrodden through his incisive pen. Foul, manipulative games of rulers he disdained the most. This has been manifest in the words of dedication in his latest book of 34 poems entitled, “Matha Hoye Geche Pakha Shudhu Urhe” -- “To those sensitive poets who can unearth the shrewd rulers’ hypocrisy and vile art of manipulation out of their sugar-coated conduct.” He was politically conscious but he maintained political detachment to the utmost. His love for his own country, and concern for people were reflected in the deathless poetic lines. In the concluding lines of his poem “Priyo March Priyo Bangladesh”, the poet says:

“This is Bangladesh

My beloved Bangladesh.

The solidified, unconquerable air

Has exposed time and again

The sky of Bangladesh

Having torn apart the darkness.”

All poets love to enjoy freedom as all normal humans do. John Milton was eloquent about the freedom of speech. Freedom is needed to foster a creative culture that demands freedom to think, freedom to express, and freedom to share. It promotes initiative, innovation, competition, and improvement. To SG, freedom was a human need but not a licence to impose whims upon others. A freedom-fighter himself, SG discloses his notion of freedom in the beginning stanza of the poem

“Manusher Niom”:

“Freedom is a different thing.

It wears a different countenance in different contexts,

In different situations, in different needs.

The river’s freedom

Consists in its point of origin

Or in its point of confluence

Or at times only in its ceaseless flow”.

After lodging his protest against dishonest rulers, he comes back to the mundane world and takes shelter in the arms of his beloved. Like Robert Browning, SG showed how a poet can at once be patriotic and romantic. In a poem entitled “Dukkho” (Sorrow) he writes:

“As I unlock my lips

Having kissed yours,

I find your lips disappeared

The marks of kisses are not to

be found even in thousand years.

Treading the same path

Using the same steps

Your lips efface after each kiss.”

Poets and philosophers tend to dislike bureaucrats. But SG used to respect those bureaucrats who practised the values of integrity and uprightness. He envisioned a kind of administration for Bangladesh which will build citizens’ capacity to meet their basic needs, which will fight against systematic deprivation discrimination, and injustice. He never approached any officer with any unlawful favours, although he had friendship with many bureaucrats of his time. Shahidul Jahir, a noted writer-civil servant, who recently died a few months ago, was one of his most intimate friends. SG was a man of high self-esteem and dignity. The inherent indomitable moral force enabled him to fight against the odds of life with matchless courage and optimism.

SG died at the age of sixty-four. His brother-in-law, his name-sake reports that he was a chain-smoker. Thus tobacco has cut his life short but poetry has immortalised him. SG is now physically absent from the world but he remains enshrined in the memory of the lovers of poetry and of those who exist as silent, non-violent protesters against persecution and injustice. Paul Zweig, an American poet claims: “A man’s life cannot be silent; living is speaking; dying too is speaking.” Samudra Gupta’s voice can be heard through his immortal poem; he is still speaking and will continue to speak although dead in person.

Syed Naquib Muslim, Ph.D, is Chairman, Bangladesh Tariff Commission.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2008 |