|

Book Review

Lascars, Sepoys and Nautch girls

James Buchan climbs

aboard the first part of a trilogy

set at the time of the opium wars

This terrific novel, the first volume in a projected trilogy, unfolds in north India and the Bay of Bengal in 1838 on the eve of the British attack on the Chinese ports known as the first opium war. In Sea of Poppies, Amitav Ghosh assembles from different corners of the world sailors, marines and passengers for the Ibis, a slaving schooner now converted to the transport of coolies and opium. In bringing his troupe of characters to Calcutta and into the open water, Ghosh provides the reader with all manner of stories, and equips himself with the personnel to man and navigate an old-fashioned literary three-decker.

He begins in the villages of eastern Bihar with Deeti, soon to be widowed; her addicted husband, who works at the British opium factory at Ghazipur; and Kalua, a low-caste carter of colossal strength and resource. Moving downstream, we meet a bankrupt landowner, Raja Neel Rattan; an American sailor, Zachary; Paulette, a young Frenchwoman, and her Bengali foster-brother Jodu; Benjamin Burnham, an unscrupulous British merchant, and his Bengali agent, Baboo Nob Kissin; and every style of nautch girl, sepoy and lascar.

Yet Sea of Poppies is a historical novel, which means that the story is only half the story. Ever since Walter Scott published Waverley in 1814, readers have turned to historical fiction not just for escape from a straitened and conventional present, but also for instruction. Scott gave his readers not merely the bizarre character-types and wide open spaces of a fantastic pre-industrial Scotland, but antiquities, dialect, history, geography and lashings of political economy. Ghosh finds the educational programme of the Scottian novel very much to his purpose.

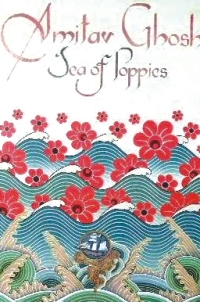

Sea of Poppies

by Amitav Ghosh

471pp, John Murray, £18.99 |

Thus he dramatises (or rather romanticises, in the sense of makes a novel out of) two great economic themes of the 19th century: the cultivation of opium as a cash crop in Bengal and Bihar for the Chinese market, and the transport of Indian indentured workers to cut sugar canes for the British on such islands as Mauritius, Fiji and Trinidad.

At a more everyday level, Ghosh creates an encyclopedia of early 19th-century Indian food, servants, furniture, religious worship, nautical commands, male and female costume and underlinen, trades, marriage and funeral rites, botany and horticulture, opium cultivation, alcoholic drinks, grades of clerk and non-commissioned military officers, criminal justice, sexual practices, traditional medicines and sails and rigging.

His technique, which was also Scott's, is to supply the maximum information that the story can support. For example, he has read the description of the great Sudder opium factory at Ghazipur published in 1865 (a little late, but it will do) by the factory superintendent, JWS MacArthur. Given that there are probably not 20 copies of MacArthur's Account of an Opium Factory on earth, Ghosh is amply justified in using it. His device is brilliant. He has Deeti rush in terror through every single shed of the factory in search of her dying husband. Yet whereas MacArthur wanted to show how the factory operated in each season, Ghosh makes all its activities simultaneous. Poppy flowers, sap and trash are processed before Deeti's terrified village eyes. Ghosh has not forgotten the agricultural calendar; it's just that he will no more waste a fact than MacArthur wasted poppy.

Indian writers in English of an earlier generation, such as the late RK Narayan or VS Naipaul, aspired to a pure metropolitan or "Oxford" English. Ghosh, like Salman Rushdie, introduces words from the Indian languages, and from the various creoles, pidgins and slangs that have arisen in India and the Asian seaports since the 18th century. He has combed the colonial-era dictionaries and lexicons for nautical speech, barrack-room slang and all sorts of thieves' and whores' argot. The most important of these sources is Sir Henry Yule's Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases (1886), which is also a particular favourite of Rushdie's. Some readers may be perplexed by such sentences as: "Jodu had been set to . . . stowing pipas of drinking water, tirkaoing hamars, hauling zanjirs through the hansil-holes." Even those who have spent years labouring at eastern languages may be baffled by Anglo-Indian transliteration and not recognise Mrs Burnham's cubber, meaning "scandal", from the Arabic khabr, meaning "news".

Yet for all its research, Sea of Poppies is full of the open air. It never, as the 18th century used to say, "smells of the lamp". Nor does it matter that Ghosh, like Rushdie, sometimes reads like Kipling and Jim Corbett and those British memoirists of the Camp-and-Cantonment school.

Historical novelists, even Scott, are often bad at love. As one might expect, Ghosh passes over for his chief romantic interest both English and natives. He lights instead on an octoroon from Baltimore and a Frenchwoman brought up in the Calcutta Botanic Garden by a Bengali wet-nurse. Their speech, respectively the "tall" American English of the 19th-century frontier and franglais, bores him silly and he does it badly. Confined by the manners of Jane Austen, these young people simply cannot get going. Ghosh loses patience - and in comes a cutlass-heaving lascar or a farting Sahib.

James Buchan's latest novel, The Gate of Air, will be published by the Maclehose Press in August.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008

|