|

Interview

Changing the Face of Feminism

Interviewed by Hana Shams Ahmed

In an article titled 'Feminism Remixed' journalist and writer Ammu Joseph writes, "The fact that women coming of age in the new millennium wish to reclaim feminism and make it their own is, I think, a fairly clear sign that it is alive, kicking and, more importantly, evolving. It certainly contradicts the common assumption that young women have no time or use for feminism." Feminism has become almost a 'dirty word' in male-dominated newsrooms. In her articles Ammu Joseph explores how the struggle for women to show that they are capable of doing as well as men have been changing over the years. She has interviewed 200 women journalists for her book 'Women in Journalism: Making News' and explored from different angles what it means to be a woman journalist today. As the variables in the society change so do the challenges. The challenges for women today it seems are quite different from those in newsrooms 20 years ago. Working as an independent journalist now it is clear that the work for Joseph was anything but easy. Carline Bennett in an article about her writes about how Joseph while preparing a report for the United Nations on women stayed up till the 4 a.m. to finish her report. In 1986 she quit The Indian Post as The Editor of the Sunday supplement magazine when the newspaper editor asked her to concentrate on food, fashion and fun.

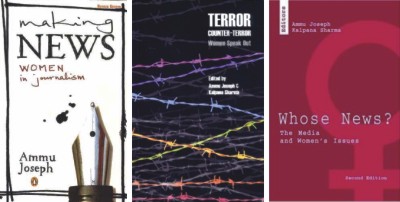

Ammu Joseph has been a journalist for 20 years. She began her career as a journalist with Eve's Weekly, for which she served as Assistant Editor for four years. She has also been a visiting lecturer in journalism for the post-graduate course in 'Social Communications Media' at the Sophia College Polytechnic, Bombay, since 1995. In addition to writing freelance for various publications in India and abroad on issues related to women, children, human development and the media, she has contributed a fortnightly column for children to The Hindu's Young World. Based in Bangalore, India Ammu Joseph is a freelance journalist, media analyst and editorial consultant. She has co-authored and edited, with Kalpana Sharma, a book entitled, Whose New? The Media and Women's Issues (Sage, 1994). Ammu Joseph has been a journalist for 20 years. She began her career as a journalist with Eve's Weekly, for which she served as Assistant Editor for four years. She has also been a visiting lecturer in journalism for the post-graduate course in 'Social Communications Media' at the Sophia College Polytechnic, Bombay, since 1995. In addition to writing freelance for various publications in India and abroad on issues related to women, children, human development and the media, she has contributed a fortnightly column for children to The Hindu's Young World. Based in Bangalore, India Ammu Joseph is a freelance journalist, media analyst and editorial consultant. She has co-authored and edited, with Kalpana Sharma, a book entitled, Whose New? The Media and Women's Issues (Sage, 1994).

She received her B.A. in English Literature from Women's Christian College in Madras, a diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia College Polytechnic in Bombay, and a B.S. in Public Communications from Syracuse University, New York. She has also been a press fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge University, England. Her other books include 'Terror, Counter-terror: Women Speak Out' and 'Storylines - Conversations with Women Writers'.

Recently at a conference in Kathmandu organised by Working Women Journalists (WWJ) of Nepal Ammu Joseph spoke about women journalists in India. She spoke to The Star magazine about what it means to be a woman journalist today.

It is a common observation throughout the region that although we see a lot of working women journalists the decision-making positions are mostly taken up by male journalists. Why do you think there are so few women journalists in decision-making positions in the media?

Actually there has been an increase of women in decision-making positions, particularly in television, and even in newspapers they have come to the second level as assistant editor. But what we don't have for the most part, are editor in chiefs etc. but in magazines women have been editors for a long time, and not necessarily just in women's magazines only either. So it has improved. But a lot of women drop out of full time employment from these publishing houses. It's quite a noticeable trend. But this is because the media houses themselves are not flexible enough. This is actually a loss to the media houses. I don't think they realise that. Because they are good at their work and they have a lot of experience and they are dropping out because they want to do something more satisfying. They want to write a book and then there are the usual problems of getting married and having children. I don't know why the media houses don't realise how important it is to retain these people by making adjustments which is entirely possible these days with the technology available. And I think, in India at least, in the metropolitan, English language media I don't think the biases is that evident anymore. But in non-metro, regional language publications we still hear from our colleagues that they are not even paid on par. In the old days the journalists wages were determined by the wage board. So everyone knew what everyone else was getting. But the unions were sort of sidelined. Nowadays journalists unions are no more relevant to negotiating salaries. And they've managed to get almost everyone they've hired in the last 15 years on to individual contracts. So no one knows what the others are getting. And many senior women journalists have said that they feel that they are not getting equivalent to what their male colleagues are getting. But we have no proof because everything is individually negotiated. Women feel slightly embarrassed to negotiate about money. So a lot of the older women feel that that is a great disadvantage. Then there is the attitude that a woman's salary is not the main source of income in a family. So even some of the single women who are in fairly high positions say that they face a lot of disadvantages. But I think younger journalists are much more confident about negotiating their salary. A lot of the older journalists also say that the definition of what an Editor is has changed. In the old days you were supposed to be well read and well educated and you had a perspective. Now there is more of a focus on the business interest.

Do you think the personality of a woman is very important in what profession she takes up? And do you think there is enough social security for women to build up such a personality?

Journalism is not one of those professions where there is routine work like in a bank for example. Journalism, if you want to do well, you have to have an initiative. It's not a lone profession. You can't be terribly shy because you have to interact with a lot of people. You need to be fairly self-confident. These things should be built into journalism training. In the old days the kind of women who went into journalism were mainly from the upper class background where families encouraged going into this profession. So most of my colleagues and I did not have any adjustment problems. And many of us went through the women's magazine routes. But now I find in the journalism schools there are a lot of girls coming from small towns from very middle class backgrounds. They are already fairly bold. They know how to negotiate their rights.

Women journalists, and any working women face similar problems in a work environment, many of which you have talked about in your book on women journalists where you interviewed over 200 women journalists. Do you want to talk a little about these problems?

First of all I want to make it clear that the book is not just about women journalists' problems. It's really an exploration of women journalists' experience in the profession and their perspective on the profession, what they think of issues including media ethics. The first chapter is about the very term 'woman journalist'. I've recorded a full range of opinions on whether such a term should be used. Some people feel it is totally irrelevant why they should be identified on their sex. They've said that they are professionals just like everybody else. Others have said that one can't really deny the fact that the world looks at them like that. The big issues that came up was 'night shift'. There are many varied opinions on that issue. Some people say that if you want to be treated as an equal you can't expect any special facilities. But others say that as long as society does not change and women have to shoulder the burden of the family and household it should be possible to accommodate it. At the same time they say that if you are not able to do night shifts your chances of getting promoted are less. So it's a very contentious and difficult dilemma but there's no black and white or one answer to any of these. Professional harassment was one of the things a lot of people identified with. But sexual harassment was at that time almost a geographical divide. It was more of an issue in the north and less of an issue in the south. I don't know if it's because people in the south don’t like to talk about it. And there is the issue of networking with people. A lot of contacts are made over the bar where male journalists drink with bureaucrats and politicians and that's how they develop contacts. If women do that their character will come into question. But then many journalists have said that these guys are so close to these news sources we've never seen a good story coming from them because they go into self censorship. But many of the women talked about the problems they face with their families. Single women talk about how difficult it is for them to get accommodation. But the book is mainly about journalism through the eyes of women, in terms of work conditions and also about the profession itself.

You said something interesting in your presentation about the definition of 'hard' and 'soft' news stories. How do you think these definitions and stereotypes came about?

Even journalists who have covered politics say that it is the easiest thing to do because politicians are dying to talk to you. The routine political reporting of going to press conferences etc which I personally call political gossip. Development is politics. Health and education are political issues. And there are issues of rights and entitlements. Those are really political issues if you understand politics as it should be understood. Even urban, civic, environment and gender issues are issues of governance. I just cannot understand how they can be considered 'soft' issues. And even if they are considered soft, why should it be less valuable or important than covering parliament. Many of the journalists who have covered both parliament and development issues say that it is much more difficult to cover development issues. No one is handing you things in a platter. You really have to do the work -- to talk to people, to gather the information, to understand the issue etc.

Quotas for women to encourage them to come to the media. Is that a good or bad thing?

Personally I don't think that is really necessary because the number of women in journalism is increasing at a very fast pace. And I think in the journalism schools in India the situation is such that you almost have to have a quota for men. It's better to encourage women to consider this as a profession and then train them accordingly so that they have a clear picture of it and think of it as an option. Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2009 |