In October 1971, OXFAM put together a document called "The Testimony of Sixty", it was made to inform the world about the humanitarian crisis caused by Bangladesh's War of Liberation. Sixty people including Mother Teresa, Senator Edward Kennedy and John Pilger wrote exclusive accounts of what they saw and the situation on the ground. The powerful document provided more than just eyewitness accounts, but insight into a tragedy of untold proportions. The following excerpts paint a devastating picture of the war of survival borne out of the war of liberation.

"I have just left one of the innumerable refugee camps which border the Indo-Pakistan frontier. A small camp it has 6.000 people (Salt Lake has 300,00): an 'acceptable' camp. I use this shocking word for nothing is really 'acceptable' in saying that misery is well organised. I saw what the Indian Government is doing to give at least shelter and something to alleviate famine. I saw, too, the efforts made by several foeign and international charities: maybe a ray of hope, but a ray only, because the situation is getting worse. The mass of refugees is growing quickly, tomorrow, their emotion being over, their conscience being relieved, the rich countries will forget Bengal, whereas it needs help more than ever.

It seems to me obvious that in the face of such a dramatic situation, private and charitable giving is not enough. Only a huge and concerted action by governments can put an end to the tragedy."

Vincent Philippe

Feuille D'avis de lausanne

"It was a Saturday and with the monsoon starting, heavy rain had fallen for nearly five hours. There was a little, almost unofficial camp, not far away from our hospital-perhaps a thousand people huddling in shelters on the roadside or even without shelter at all. In a few large bamboo type huts a number of families had crowded-perhaps 12 families to a hut.

But the huts had been built below flood level and the water had risen in the huts to a depth of about two feet. A crowd stood around one in particular. With the endless rain the roof had given way. Most of the people had got out. But a baby, knocked on to the ground had either drowned

or suffocate and its little body was held by a weeping mother. Guilty of nothing, life was suddenly over. I could not look at the parents who had come so far only to find this extra tragedy at the end of a road of tears."

Monseigneur Bruce Kent

War on Want

"In India I visited refugee areas along the entire border of East Bengal-from Calcutta and West Bengal in the west-to the Jalpaigury and Darjeeling districts in the north-to Agartala in the State of Tripura in the east. I listened to scores of refugees as they crowded into camps, struggling to survive in makeshift shelters in open fields or behind public buildings-or trudging down the roads of West Bengal from days and even weeks of desperate flight. Their faces and their stories etch a saga of shame which should overwhelm the moral sensitivities of people throughout the world. I found that conditions varied widely from one refugee camp to another. But many defy description. Those refugees who suffer most from the congestion, the lack of adequate supplies and the frightful conditions of sanitation are the very young-the children under five-and the very old. The estimates of their numbers run as high as fifty percent of all the refugees. Many of these infants and aged already have died. And it is possible-as you pick your steps among others-to identify those who will be dead within hours, or whose suffeirngs surely will end in a matter of days.

It is difficult to erase from your mind the look on the face of a child paralyzed from the waist down, never to walk again; or a child quivering in fear on a mat in a small tent still in shock from seeing his parents, his brothers and his sisters executed before his eyes; or the anxiety of a 10-year-old girl out forging for something to cover the body of her baby brother who had died of cholera a few moments before our arrival. When I asked one refugee camp director what he would describe as his greatest need, his answer was "a crematorium". He was in charge of one of the largest refugee camps in the world. It was originally designed to provide low income and middle income housing, and has now become the home for 170,000 refugees.”

Senator Edward Kennedy

"The life, or death, of Bangla Desh is the single most important issue the world has had to face since the decision to use nuclear weaponry as a means of political blackmail. It is that, because never before have the world's poor confronted the world's rich with such a mighty mirror of Man's Inhumanity.

Usually we in the West, who are the rich, can dismiss or rationalize famine, unexpected disaster and even mass extermination by simply noting that the poor, who are characterized by the people of Bangla Desh, are numerous and ought to be pruned. If only, we say, they could organize their own resources and subscribe to decent, Western politics. Surely they are expendable. We even allow ourselves a good snigger at places crying out against odds we cannot comprehend; places like the Congo and the ravaged republic of the Americas. None has followed the Western wisdom of democracy, and so they must suffer. A pity.

Bangla Desh has called our bluff. The people of what was East Pakistan, who represented the majority of the state of Pakistan, voted to be a democracy and to be led by moderate middle-class. Western-styled politicians. Foolishly perhaps, they chose our way in their pursuit of freedom, in spite of problems we have never had to face.

And for this reason alone, they are being exterminated and enslaved in a manner reminiscent of Adolf Hitler, over whom the world went to war. But, of course, he was exterminating Europeans.

We in the West have no intention of going to war over Bangla Desh. Instead, through our elected government, we have contributed what amounts to one week's survival pocket money to the refugees of Bangla Desh, now petrified in India. India must provide the rest.

It is a cliché but it remains the truth of today: that there will be peace and civilization and "progress" throughout the planet only when the rich minority-us-begin to close the gap between ourselves and the poor majority. We have the opportunity of beginning to do that in Bangla Desh: for this is a cause in which we may locate our lost, twentieth century soul. Oh yes, and save some human lives.”

John Pilger

Daily Mirror

"The long lines of bamboo huts flattened by rain become longer every day. In these hovels people sleep on the ground, defecate along the paths and giant crows hover above. Fifty children fight over an egg we had given because we didn't have the courage to eat it in front of them. In the mud a woman heaves, groans, and gives birth. The poorest of Norwegian lumberjacks, the most deprived Welsh miner, is a thousand times, ten thousand times richer than the happiest of the ten million refugees. If we can accept the potential death of these ten million refugees it means that we can accept the ten million deaths of Auschwitz. The powers which united to give freedom to the oppressed people in 1944 cannot fail to unite today to save the innocent victims of this tragedy. Their destiny is linked with ours. If we let them die it means our civilizations is already dead.”

Claude Mosse

Radio Suisse Romande

"I have been working among the refugees for five or six months. I have seen these children, and the adults, dying. That is why I can assure the world how grave the situation is and how urgently it must help.

The appeal is to the world-and the world must answer.”

Mother Teresa

The Unknown Aid Worker

|

| Julian Francis |

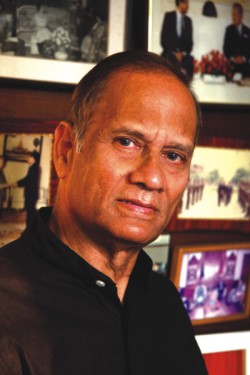

The war of liberation may have been fought in Bangladesh, but the fallout of the war was largely dealt with in India. Millions of refugees fled the country as the nine-month war ravaged its resources and people. They marched in long lines to the border and made their way into India, for food, shelter, clothing, housing and peace of mind. Innumerable people lost their lives in the conflict and thousands of others died in the refugee camps. But millions were also safely taken care of in those very same refugee camps as people gave their heart and soul to help those displaced by the war. One such person was Julian Francis, an aid worker with OXFAM who did more for Bangladeshi refugees than most will ever know. Julian was in charge of OXFAM's Refugee and Relief Programme which assisted over 500,000 men, women and children in refugee camps in the Indian states bordering Bangladesh. Aside from liasing with Senator Edward Kennedy he also helped put together a document titled 'Testimony of Sixty'. Recently he spoke to Nader Rahman about his experiences with refugees, camp life and his continued work in Bangladesh.

What were your first experiences with the refugee camps?

The first contact with the refugees was at the Bongaon/Benapole border because by that time there was quite a fear of cholera. The west Bengal government particularly were worried that cholera would sweep through the city and were experimenting with what they called in those days 'jet injectors', which were sort of guns that sprayed cholera vaccine at high pressure through the skin so you didn't need a needle. So as the refuges were coming across the border, they were being shot with the cholera vaccine gun. The west Bengal health authorities wanted to vaccine a buffer zone around that part of Calcutta. They asked us to get one million doses which somehow we managed to arrange in less than 72 hours. There was a Ghandhian ashram in Bongaon also the Catholic Church set up a refugee camp, so immediately we were supporting their work of those sorts of organisations as well as Mother Teresa sisters in different camps. So for quite a number of weeks at the beginning when I was setting up the administration and coordination for Oxfam's programmes Mother Teresa would ring me every morning with a shopping list. She wouldn't say good morning, she would start by saying God bless you Julian, so that was her way of saying hello.

How did you manage to medically take care of so many refugees, the numbers must have been staggering?

We took a decision right at the beginning that we shouldn't be calling lots of expatriate people, doctors and nurses and other volunteers or paid people from Europe. Because we had all the local connections we needed and we could mobilise medical students and Indian doctors which is what I did. The other foreign agencies did not like our decision, because they were doing a lot of publicity at Heathrow with white faces going places to save people. But we said no, it's far more cost effective to do it from and in India.

Were there enough consenting pro bono doctors in India to take care of up to 10 million refugees?

Well there probably weren't that many but then somehow we found out that a medical student in one of the colleges was actually the daughter of a well-known Ghandian leader, Narayan Desai. So we went to visit her to see whether we could organise anything through the college. She managed to get the college authorities to agree that the students could go out on rotation and if they did a months' voluntary service in any of the camps that we (OXFAM) were involved with than it would be regarded as part of their social and preventive medicine section of their MBBS. After it was rubberstamped by Calcutta University the other medical colleges in Calcutta also offered their personnel. Then it got publicity that it was a sort of Indian operation, and Bombay medical colleges started sending batches over.. And of course that experience was unique for them and moulded their lives for the future. Other medical students even came from places as far off as Gujrat, Punjab and Orissa.

There must have been some terrible sights in those refugee camps. Is there any one in particular that stands out?

The most dramatic experience I had early on was when I visited some camps in Jalpaiguri in the northern part of western Bengal. There were not enough able-bodied men in the camp to dig graves for the cholera victims at that time. So the camp director had asked for army people to come and help. But before they arrived whoever was able to dig was digging, so I spent a day digging graves and we had to dig mass graves because there were hundreds dying all the time. It was an experience I will never forget.

What was the morale like among the refugees?

The refugees were coming over with what could only be called 'frozen faces; because they were still in shock. Many of them had left behind burning villages, many of them had lost members of their family to the Pakistan army and even to friends turned collaborators. Older people just through the physical effort of trekking out of the country even died of heart attacks. There was tremendous suffering and a lot of shock. I suppose in many cases what forced the adults out of shock was the fact that they had to carry on looking after their young children.

Could you explain your role in preparing the document `A Testimony of 60` and the reaction to it after it was published?

Oxfam published this document in record time. A lot of these statements were collected by me in Calcutta and then sent by telex. It had a good reaction with government leaders from Western Europe and the Commonwealth. The publication date was 21st of October and it was only 10 days later that (Senator Ted) Kennedy got it included in the Senate records. And to get it included without any vote against it was quite remarkable considering the government that was in power then (Nixon).

How long have you been in Bangladesh?

I came to Bangladesh first after the cyclone of 1970, the second time I came was about 10 days after Sheikh Mujib returned. I drove by land from Calcutta to Dhaka, I think it took us more than 24 hours and that was largely because of ferry problems. But the volume of people returning during those days was amazing, the singing, shouting and joy was quite extraordinary. I remember as if it was yesterday driving into Dhaka about midnight past the old airport and there was no one, no vehicle, nobody in sight! Then suddenly we were surrounded by the army, we didn't realise that there was still curfew in the city.

Since then I've been in Bangladesh almost every year since independence, but not working full time. I was in India from '67 to '83 but I visited often. Then I was working for a Canadian organisation in Bangladesh from '85 to '92. I came back again in '98 with the International Red Cross. In the 2000 I left the Red Cross and joined the European Union commission of land project Adarasha gram. Then six years later I finally moved immediately into the Chars livelihood program with DFID. In a way I have never really left Bangladesh.

Banga Bir M.A.G. Osmany

|

Banga Bir M.A.G. Osmany |

A True Hero

Syed Zain Al-mahmood

He was not a tall man, but he towered above everyone around him. His seniors respected him, his comrades revered him. Those who knew him were struck by his passion and his integrity. General M.A.G. Osmany, Commander in Chief of the Mukti Bahini, lived by the watchwords of honour, freedom and service. Throughout his colourful life, regardless of his personal circumstances, he never hesitated to heed his country's call.

On April 9, 1971 Captain Azizur Rahman, commanding a unit of the Bangladesh Forces, was engaged in a pitched battle against Pakistani army troops near the Keane Bridge leading into Sylhet town. Both sides had suffered heavy casualties. Pinned down by superior firepower, the young officer was trying to rally his troops when his jeep was fired upon and fell into the Surma.

“As a young captain with no battle experience, I tried to maintain the morale of my men by visiting the front-line troops. We fought fruitlessly against a formidable adversary only to be violently repulsed,” recalled Capt. Aziz (later Major General Azizur Rahman Bir Uttam). “Amidst the confusing and deafening sounds, a voice suddenly spoke behind me: "Young man, what's happening?"

It was the C-in-C himself. “I could never imagine that a person of the stature of Colonel Osmany (I had never seen him before) would have the guts and curiosity to be on the battlefield. He must have travelled a long way on foot to reach me. It was very dangerous.”

After a brief introduction, Osmani quickly sized up the situation. “Finding me at a puzzling loss, the C-in-C rescued me,” said Major Gen. Azizur Rahman. “He advised me to reorganise, break contact with the enemy, and withdraw to a better defensive position (he suggested the next position) after burying the dead fighters and collecting the wounded. He further cautioned me to not allow the Pakistan army to pursue my troops.”

This incident, described by one of his comrades in arms, illustrates Osmany's courage and selfless devotion to the cause. “Papa Tiger”, as he was affectionately known, came out of retirement to lead the Liberation Forces. The very name of Colonel (later General) Osmany electrified all Bangali officers, and struck fear into the hearts of the enemy.

Muhammad Ataul Ghani Osmany became a soldier almost by accident. Born in Sunamgonj on 1st September 1918, he was headed for the civil service when the Second World War broke out. A graduate of Aligarh Muslim University, Osmany had already qualified for the Indian Civil Service. But fate had other things in store. In 1939 Hitler was taking Europe by storm, and the Japanese army was advancing through Burma. Osmany answered the call to arms. He joined the British Indian Army and saw action on the Burma front, receiving promotion to the rank of Major.

Muhammad Ataul Ghani Osmany became a soldier almost by accident. Born in Sunamgonj on 1st September 1918, he was headed for the civil service when the Second World War broke out. A graduate of Aligarh Muslim University, Osmany had already qualified for the Indian Civil Service. But fate had other things in store. In 1939 Hitler was taking Europe by storm, and the Japanese army was advancing through Burma. Osmany answered the call to arms. He joined the British Indian Army and saw action on the Burma front, receiving promotion to the rank of Major.

After the partition, Osmany joined the Pakistan Army on October 7, 1947, and was soon promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. He attended the staff college at Quetta where he served alongside (then) Major Yahya Khan, Tikka Khan and A.A.K Niazi, all of whom ironically were destined to lead the Pakistan army against Mukti Bahini commanded by Osmany in 1971. The recruitment policy at the time was weighed against Bangali officers and Osmany, fearless soldier that he was, spoke out against this discrimination. He was sidelined, and his promotions held up. Col. Osmany retired in 1967. He joined the Awami League and was elected a member of the Pakistan national assembly in the 1970 elections.

Col. Osmany was present at the house of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman when Bangali officers informed Awami League leaders of the departure of Yahya Khan and army movement. After failing to persuade Bangabandhu to leave, Osmani shaved off his famous mustache and made for the Indian border.

With the formation of the Bangladesh government on 17 April 1971, Colonel Osmany was appointed Commander-in-Chief of all Bangladesh Forces. He was later promoted to the full rank of General during the Bangladesh Sector Commanders' Conference in July 1971. Under his direct command, Osmany divided up the entire Bangladesh territory into 11 sectors. Each sector was under the command of a trained military officer with the title of Sector Commander. Each sector also had sub-sectors with sub sector commanders. Osmany orchestrated the valiant struggle of the Mukti Bahini against the much better equipped Pakistan army.

After independence, Osmany was included in the cabinet of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He resigned from the cabinet in May 1974. After the introduction of one-party system of government through the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution in 1975, he resigned from the Jatiya Sangsad and also from the primary membership of the Awami League protesting the abolition of democracy.

M.A.G. Osmany was appointed an Adviser for Defence Affairs by Khondaker Mostaq Ahmed on August 29, 1975, but he resigned immediately after the killing of four national leaders inside the Dhaka Central Jail on November 3, 1975.

In 1984, Osmany, victorious soldier of many battles, lost the fight against cancer. The nation lost a valiant son. A lifelong bachelor, Osmany left behind his ancestral house in Dayamir, Sylhet where visitors still gather. His favourite Alsatians are no more, but the remains of the pond that he dug himself and the wide lawn remind visitors of the great man.

Banga Bir M.A.G Osmany always carried the courage of his convictions. In a day and age when unselfish patriots are sorely needed, M.A.G Osmany was a model of selfless service. He was a man who truly did everything for a reason, a purpose, not for himself or for his own glory, but for the glory of the nation.

Ataul Ghani Osmany defended freedom. That will be his lasting legacy.

The Uprising of March 19

Ershad Kamol

|

Major General (retd) Moinul Hossain Chowdhury Bir Bikram |

March 19, 1971. A mob created a barricade on the road near Joydebpur intersection so that a contingent of the Pakistani Army, led by Brigadier Jahenzeb Arbab, cannot reach the East Bengal Regiment at Joydebpur Palace. A rumour spread that the contingent had gone to disarm the Second East Bengal Regiment at Joydebpur, the battalion was manned predominantly by Bangali officers and soldiers. Brigadier Arbab, a Pathan, ordered the battalion to clear the road and if need be shoot at the mob. A Bangali Major of the battalion did not carry out the order of the Brigadier, rather tried to make the agitated mob understand the situation. However, the Brigadier became very angry when someone from the mob fired on the army and ordered to retaliate. A non-Bangali soldier carried out the order and fired on the mob killing two people on the spot and wounding many. Later another wounded person also died. Ultimately a curfew was declared in the area. The reluctance of the Bangali officer to carry out the order of the Brigadier was considered an act of 'mutiny' by the Pakistani Army.

Brigadier A.R. Siddiqui, the then Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR) chief who was also the Press Adviser to President Yahya Khan, in his book titled "East Pakistan the Endgame", published from Oxford University Press, writes, "On the same day (March 19), a larger and much more serious incident also took place. A brigade commander (Brigadier Arbab Jahenzeb of 57 Brigade), who was returning from Joydebpur after inspecting one of his battalions, the Second East Bengal Regiment, was mobbed by angry Bangalis near a level crossing. He asked the mob to disperse and clear and way for him. The mob refused, and someone in the crowd opened fire. The brigadier ordered his men to retaliate but the Bangali troops refused. This marked the beginning of mutiny."

The Bangali Major, who refused to follow the order to fire on his countrymen, was none other than Major General (retd) Moinul Hossain Chowdhury Bir Bikram, a former Adviser to the Caretaker Government of Bangladesh.

According to General Chowdhury like many other incidents during the Liberation War, the incident on March 19, 1971 has been wrongly presented. Which is why there is so much confusion amongst the younger generation even after 38 years of our Liberation.

Explaining the incident General Chowdhury says, "In fact, Brigadier Jahenzeb Arbab, who led 'Operation Search Light' on the first hour of March 26 on the Bangalis, and 70 other Pakistani Army carrying heavy weapons of 57 brigade from Dhaka Cantonment went to ascertain the loyalty of the Bangali-led Second East Bengal Regiment at Joydebpur. But being guided by a rumour that the Punjabi Army came to disarm the Bangali soldiers, thousands of locals created the barricade so that the Army from Dhaka Cantonment could not reach Joydebpur. Seeing the agitated mob, I requested them to go away instead of following the order of the brigadier to retaliate. For a few minutes I tried to make them understand that if they continue to show their resistance, the Punjabi soldiers would realise that we were revolting against the Army, which would be a premature action. However, they did not listen to me. But, the brigadier became angry with me seeing such initiatives instead of taking any action. Subsequently, I ordered a warrant officer to fire on the ground so that the locals go away, though the Brigadier kept on ordering me to shoot at the mob. All on a sudden, taking a weapon from a soldier someone from the mob shot at the troops. One soldier wounded. Then the brigadier himself took control and ordered to shoot. Then a non-Bangali warrant officer fired at the mob that killed two civilians. Then the mob left and the barricade was removed. Subsequently the troops left for Dhaka Cantonment. I saw the anger and mistrust in the eyes of Brigadier Arbab Jahenzeb."

"At that moment even the troops led by Brigadier Jahenzeb Arbab did not dare to use heavy weapons considering the Bangali troops might react, since the Pakistani Army were suspicious about our activities from the beginning of March 1971", he adds.

"In fact, the March 19 incident was not an isolated occurrence, rather part of a series of consequences", continues General Chowdhury, "I had the opportunity to know the intention of the Pakistani Army high-ups, since for two years I served as the Aide-de-Camp (ADC) to the Chief Martial Administrator of East Pakistan Major General Khadem Hossain Raja before joining the Second East Bengal Regiment at Joydebpur in 1970. It was clear to me that the Army would not accept the six-point demand and other political movements of Bangladesh Awami League. When the military took time to hand over power after the national elections in 1970, it was clear to me that Army high-ups were planning something different to quash the movement. On the other hand observing the ongoing political activities I anticipated that Bangabandu might declare Independence on March 7. If that happened a war would be likely. So, I talked with my Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel Masud, initially, then with other Bangali officers and soldiers. At the same time I used to gather information from Dhaka Cantonment. The Army at Dhaka Cantonment became suspicious about the ongoing activities of Second East Bengal Regiment at Joydebpur. Which is why Brigadier Arbab came to the Joydebpur Palace to test the loyalty of the rest of the officers."

According to Major General (retd) Moinul Hossain Chowdhury Beer Bikram, the March 19 incident virtually separated the Second East Bengal Regiment from the 57 Brigade. Within three days the commanding officer Lt Colonel Masud was called at Brigade; he faced brutal torture during the nine-month long Liberation War at Dhaka Cantonment, says General Chowdhury. He continues, "Troops at Dhaka Cantonment could not move to control our mutiny, since they were not prepared enough to attack a battalion at that time. We took the opportunity and isolated the non-Bangali officers and soldiers at Joydebpur. We knew that our job with the Pakistani Army had ended on March 19 and we had to face court martial unless the Liberation War began. In fact, I was one of the officers against whom the Pakistani Army carried out court martial in absentia during the Liberation War."

In fact, the soldiers and officers of the Second East Bengal Regiment used to patrol the roads and Joydebpur was virtually under the control of the regiment since March 19, says General Chowdhury. According to him they began to move the families of the soldiers to safe places and prepared for a war against the Pakistani Army. "On March 27 when we came to know that Bangali officers in Comilla and Chittagong cantonments had also revolted, that same night, breaking into the ordinance factory, I led the battalion towards Mymensigh to join the other freedom fighters. Major Shafiullah, who later became chief of the Bangladesh Army after the Independence, who was also a major of the regiment, left Joydebpur on March 27 morning and received us at Mymensingh."

During the Liberation War Major General (retd) Moinul Hossain Chowdhury Bir Bikram served as the commanding officer of Bengal Regiment under S Force. Winning many important battles such as Akhaura battle, his battalion reached Demra, Dhaka on December 16. He also served as a Battalion Commanding under Z Force in the crucial Kamalganj battle.

Shirin Banu Mitil

‘The Girl With a Gun’

Jackie Kabir

|

Shirin Banu Mitil |

Her name is Shirin Banu Mitil but she was called Mitil Khondaker during the war of independence. Mitil was born in a family where being active in politics was quite normal. Her mother Selina Banu was an active member of the Communist Party since 1938 and her father got involved with the same party in 1940. Selina Banu won in the election with a NAP (National Awami Party) ticket from a mud hut. Mitil's maternal grandparents' house where she grew up was a centre of communist activities. So, none of her family members was surprised when she decided to fight in the war along with her two male cousins. She disguised herself as a boy wearing her cousin's clothes and sneakers. Mitil was the president of Chhatra Union in Pabna district. At that time, she was also a student of Victoria College. Her cousin Jahid Hasan Jindan was Chhatro Union's General Secretary. They joined the freedom fighters in Pabna. The independence war of Bangladesh left a lot of scars in many of its citizens. Though it's been more than 35 years since then, the wounds of war are still very raw.

In what circumstances, did you join the war?

As I grew up in a family which was very conscious about the politics of the country and was directly involved in it, it was hardly a surprise to my family members when I decided to join the war. My aunt, whose two sons were my companions, ordered them to fight for their country and commented that she didn't want them to get shot at the back. They were an inspiration for me.

How did your family react to the fact that you were joining the war?

My eldest aunt was the decision maker of our joint family. As my cousins got ready to go for the war, I was desperate to go with them but didn't know how. But I was making banners and festoons like everyone else at that time. Suddenly, my cousin Jindan asked me to dress like Pritilata Waddedar and go with them. Pritilata was an inspiration for many women at that time of war. I put on men's clothes and went in front of my aunt and she told me she thought I was ready to join the war. She asked me to take off my gold chain and earrings and carry them with me in case I needed them.

How did you fight in the war?

One has to understand when we say 'fight the war' we don't always mean fighting with a gun or a rifle. Women all over Bangladesh fought the war - some physically, some helped the wounded soldiers, some cooked for them, some sacrificed everything in order to free their homeland. They are all freedom fighters. There were three stages in Bangladesh's war of independence. The first was the primary defense stage; then came the preparatory stage and then was the severe counter-fighting stage. In Pabna district, the first stage started on 25th March and lasted till 9th April. All the 240 Pakistani military officers were killed there. As the military started torturing the people in Pabna on the night of 25th March, the public and freedom fighters together took part in the revolt. Most people didn't have any weapon so they came out with sticks, knives whatever they could get hold of. The women were driven by only one dictum “either kill or die.” Those of us who had the weapon were practicing how to fire. It took us only half an hour to learn to use rifles. Pabna was freed on 30th March. Then the freedom fighters' contingent proceeded towards Kushtia and then Chuadanga. I was moving with freedom fighters dressed as a man all the time. While going to Chuadanga from Kushtia, Jindan and I were left behind, as there was no space in the vehicle. We met the police in charge and political leader Aminul Islam Badsha and two Indian journalists in Kushtia camp. Later we reached Chuadanga with some journalists in the same jeep. As the fighters ran out of ammunition, we were sent to the border to get more ammunition from the Bangladesh Shohayok Committee. When I returned I was told that a journalist had published my photo with the news titled “A shy girl with a gun” in the The Statesman newspaper of India. I lost my chance to take part in the war as a male fighter. While my companions were sent to different camps I was sent to Ila Mitra's house. She was the famous anti-British revolutionary in Nachol. Both Ila and her husband Romen Mitra became very good friends of mine.

Do you think nine months was too short a time for winning independence?

We never thought we would win the war in nine months. We were thinking of the Vietnam war and thought that we may have to fight for years to come. But India intervened as it was a great convenience for them also. About one crore people were already in Calcutta as refugees. But hadn't India came to help us, independence would have taken a longer time.

Do you think Bangladesh is taking a long time to develop just because it gained independence in a very short time?

Our war began from the demand of autonomy for Bengal. Later it was transformed into a war of independence. We dreamt of a country where there would be no hunger and no scarcity of food. After our independence what we needed was a government which would have participation of all political parties. They would be united with nationalistic values. Only then would we be able to make the country we had envisioned.

How do you feel about the women who were victimised during the war?

I don't understand why the society should be so hostile towards the victimised women. I think they should be honoured and accepted as freedom fighters. The war came at their cost as well. In Islam remarrying a widow is considered to be a pious deed. So why wouldn't it be possible to accept a woman who has been physically violated for the sake of her country? Why wouldn't the family accept her as 'Birangona'? Why won't we feel proud that a Birangona is part of my family? It's a pity that even the title 'Birangona' has been mocked at in our country.

Do you think the war criminals should be tried under the existing laws?

Yes, if you ask me. The trial of war criminals was started in 1973. There were 12,500 war criminals in Bangladesh. It is wrongly said that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman pardoned all the war criminals. Bangabandhu couldn't have pardoned those who were the collaborators of the heinous acts carried out by the Pakistani army. He only meant those who helped the Bangalis, the freedom fighters while acting as friends with the Pakistani army. There were many who saved entire families by feigning to be friends with the enemy. But those who pre-planned to kill the unarmed Bangalis can never be forgiven and we all want to see them under trial for the crimes they committed.

It is Time

The parliament has passed a bill to try the

war criminals now is the time the government

takes concrete steps to start the trial

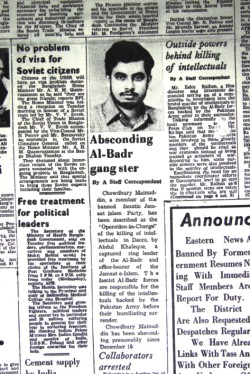

Ahmede Hussain

During our nation's Liberation War when the whole nation was fighting the occupying Pakistan army, a bunch of thugs and killers mostly belonging to the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), Muslim League (ML) and Nizam-e-Islam (NI) formed three different groups of killers and rapists. These killing squads-- Razakar, Al Badr and Al Shams--in the nine bleak months of 1971 carried out atrocities on the innocent Bangali population of the country.

During our nation's Liberation War when the whole nation was fighting the occupying Pakistan army, a bunch of thugs and killers mostly belonging to the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), Muslim League (ML) and Nizam-e-Islam (NI) formed three different groups of killers and rapists. These killing squads-- Razakar, Al Badr and Al Shams--in the nine bleak months of 1971 carried out atrocities on the innocent Bangali population of the country.

Members of the Razakar, Al Badr and Al Shams spread their tentacles all over the country to provide the information of movements of the freedom fighters to the Pakistan army and worst still they committed one of the most gruesome human rights abuses in recent human history by abducting Bangali women, some even in their early teens, to be sent to the concentration camps of the Pakistan army. In the last few days of the war, when these vile forces saw their orgy of killing and rape drawing to a brutal end, they formed killing squads, which led the abduction and killing of Bangali intellectuals. The discovery of mass graves and newspaper reports of those days prove that some leaders of the JI, NI and MIL and their student and youth wings were involved in acts of mass murder. Siddik Salik, who served as a Major in the marauding Pakistan army in 1971, in his book 'Witness to Surrender' says, "The only people who came forward (to help the Pakistani army butcher and rape innocent people) were 'the rightists like Khwaza Khairuddin of the Council Muslim League, Fazlul Qader Chaudhry of the Convention Muslim League, Khan Sobur A Khan of the Qayyum Muslim League, Professor Ghulam Azam of the Jamaat-e-Islami and Maulvi Farid Ahmed of the Nizam-e-Islam Party."

The crimes that these butchers have committed are no less gruesome than those perpetrated by Hitler and his Nazi cohorts. The trial of these bunch of mass murderers started no sooner than the country's independence in 1971. On January 24, 1972, the Collaborator's Act was promulgated; by October 1973, over 37,000 suspected war criminals were arrested of whom 26,000, against whom there was no clear evidence of killing, rape and arson, were pardoned under a general amnesty. When Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was murdered on the dark night of August 15, 1975, 11,000 suspected killers and rapists were in jail, facing trial. The JI, NI and ML were banned for their role in war crime. After the death of Bangabandhu, the ban was lifted and the government of Ziaur Rahman, which usurped power in a bloody coup d'état in 1975, made a known collaborator of the Pakistani regime the country's Prime Minister.

The rehabilitation of the collaborators of the Pakistan army continued throughout the eighties and nineties of the last century. In the last government led by Zia's widow Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) chief Khaleda

The rehabilitation of the collaborators of the Pakistan army continued throughout the eighties and nineties of the last century. In the last government led by Zia's widow Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) chief Khaleda

Zia, two known war criminals were given important portfolios; of them includes Ali Ahsan Mojahed, who was quoted to have said by “Daily Sangram” on October 15,1971: "The youths of the Razakars and al-Badar forces and all other voluntary organisations have been working for the nation to protect it from the collaborators and agents of India." In the last caretaker government's regime, he, also secretary general of the JI and head of the Al Badr paramilitia, said no war crime had been committed in 1971. His comment and the subsequent diatribes of some war criminals and their sympathisers have proven that members of the JI does not hold an iota of remorse for actively participating in the genocides of 1971.

In fact, as an issue, the trial of the war criminals has been one of the deciding factors in the east general elections. The BNP, which went to the elections keeping its electoral alliance with the JI intact, was routed in the polls as the party was seen by voters, especially the younger ones, as war crime sympathisers. In its electoral manifesto, the Awami League has promised that it will bring the killers of 1971 to the book. Now that the party holds an absolute majority in the parliament, it is time to take the nation forward to that direction.

The AL-led Grand Alliance government will significantly lose its popularity if at the end of its term the party fails to try at least most of the known war criminals. During the Liberation War, because the Communist Soviet Union supported our liberation struggle, the US and its allies sided with the Pakistani junta by providing it with military logistics and diplomatic support. The second week of December 1971, witnessed the arrival of the United States Seventh Fleet's carrier taskforce 74 in the Bay of Bengal. Time, however, has changed: Now the US is a good friend of our country and an important strategic ally. One hopes that as a time-tested friend of the people of Bangladesh and a friend that wants to see democracy and rule of law flourish in Bangladesh, the US will support the efforts of the people of Bangladesh to bring the war criminals of

The AL-led Grand Alliance government will significantly lose its popularity if at the end of its term the party fails to try at least most of the known war criminals. During the Liberation War, because the Communist Soviet Union supported our liberation struggle, the US and its allies sided with the Pakistani junta by providing it with military logistics and diplomatic support. The second week of December 1971, witnessed the arrival of the United States Seventh Fleet's carrier taskforce 74 in the Bay of Bengal. Time, however, has changed: Now the US is a good friend of our country and an important strategic ally. One hopes that as a time-tested friend of the people of Bangladesh and a friend that wants to see democracy and rule of law flourish in Bangladesh, the US will support the efforts of the people of Bangladesh to bring the war criminals of

1971 before justice.

The government should immediately form a tribunal with a High Court judge as the head under the International (Crimes) Tribunal Act 1973. It should also pass a law in the parliament making war crime denial a crime-- Germany has already outlawed holocaust denial, many European countries also have such laws.

The matter of the JI, NI, ML and other such organisations, participation in the war crimes as a political entity has to be probed. Democracy allows freedom of speech and movement; having said that, a democratic society needs to build its own mechanism to safeguard itself from those who want to destroy the very foundation on which it stands. Democracy will not take a firm footing in our country if the criminals who committed the worst crimes against humanity, not to mention, against the people of our country remain free.

It is heartening to see the government has barred the suspected war criminals from travelling abroad. Transparency, respect for human rights and rule of law should be our guiding principles in dealing with the war criminals.

There are some, small in number though, who believe that the trial of war criminals will breed extremism in the country, as they see the JI is the 'biggest moderate Islamic party' in the country. This analysis runs the risk of equating Bangladesh's socio-political conditions with that of Pakistan's. Unlike Pakistan, the JI in Bangladesh, as the last elections have proven, does not wield a mass support base, and the party does not work as a buffer between extremism and democracy. Bangladesh has an unofficial two-party system, when it comes to the elections or lending their political support, Bangladeshis have voted for two major political parties: in the general elections, the JI has never bagged more than 8 percent of total votes cast. The party has always become a distant fourth after Gen HM Ershad's Jatya Party. In fact, the trial of the war criminals will be a chance for the JI to clean its rank of its tainted past. As a new beginning, the JI should drop war criminals from its leadership and swear allegiance to Bangladesh and everything the country stands for.

The government should start the trial as soon as it can. The crime that has been committed against this nation and its people in 1971 must not go unpunished. The blood of the martyrs is crying out for justice, we have ignored it for 37 long years; history will not forgive us if we fail this time.

The International Crimes (Tribunal) Act 1973, says: "…A Tribunal shall have power to try and punish any person irrespective of his nationality who, being a member of any armed, defence or auxiliary forces commits or has committed in the territory of Bangladesh, whether before or after the commencement of this act, any of the following crimes.

The International Crimes (Tribunal) Act 1973, says: "…A Tribunal shall have power to try and punish any person irrespective of his nationality who, being a member of any armed, defence or auxiliary forces commits or has committed in the territory of Bangladesh, whether before or after the commencement of this act, any of the following crimes.

(2) The following acts or any of them are crimes within the jurisdiction of a Tribunal for which there shall

be individual responsibility, namely:-

(a) Crimes against Humanity: namely, murder, extermination enslavement, deportation, imprisonment, abduction, confinement, torture, rape or other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population or prosecutions on political, racial, ethnic or religious grounds whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated;

(b) Crimes against Peace:

namely planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances;

(c) Genocide: meaning and including any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy in whole or in part, a national ethnic, racial, religious or political group, as such:

(i) killing members of the group;

(ii) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(iii) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(iv) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(v) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group;

(d) War Crimes: namely, violation of laws or customs of war which include but are not limited to murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave labour or for any other purpose of civilian population in the territory of Bangladesh; murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war or persons on the seas, killing of hostages and detenues, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages or devastation not justified by military necessity;

(e) Violation of any humanitarian rules applicable in armed conflicts laid down in the Geneva Convention of 1949;

(e) Violation of any humanitarian rules applicable in armed conflicts laid down in the Geneva Convention of 1949;

(f) Any other crimes under international law;

(g) Attempt abatement or conspiracy to commit any such crimes;

(h) Complicity in or failure to prevent commission of any such crimes.

About the formation of the trial the Act says: (1) For the purpose of section 3, the Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, set up one or more Tribunals, each consisting of a Chairman and not less that two and not more that four other members.

(2) Any person who is or is qualified to be a Judge of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh or has been a Judge of any High Court or Supreme court which at any time was in existence in the territory of

Bangladesh or who is qualified to be a member of General Court Martial under any service law of

Bangladesh may be appointed as a Chairman or member of a Tribunal.

(3) The permanent seat of a Tribunal shall be in Dacca.

Provided that a Tribunal may hold its sittings as such other place or places as it deems fit.

(4) If any member of a Tribunal dies or is, due to illness or any other reason, unable to continue to perform his functions, the Government may, by notification in the official Gazette, declare the office of such member to be vacant and appoint thereto another person qualified to hold the office.

(5) If, in the course of a trial, any one of the members of a Tribunal is, for any reason, unable to attend any sitting thereof, the trial may continue before the other members.

(6) A Tribunal shall not, merely by reason of any change in its membership or the absence of any member thereof from any sitting, be bound to recall and re-hear any witness who has already given any evidence and may act on the evidence already given of produced before it.

(7) If, upon any matter requiring the decision of a Tribunal, there is a difference of opinion among its members, the opinion of the majority shall prevail and the decision of the Tribunal shall be expressed in terms of the views of the majority.

(8) Neither the constitution of a Tribunal nor the appointment of its Chairman or members shall be challenged by the prosecution or by the accused persons of their counsel.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009