|

Book Review

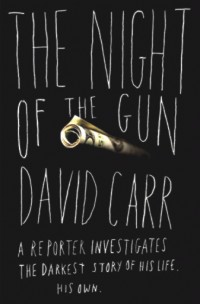

The Night of the Gun

Jennifer Reese

The memoir doesn't get much respect and why should it? Starting sometime in the 1990s, just about every American and her hamster decided to publish an account of their wretched childhood, witchy socialite stepmother, alcoholic homeless father, or struggles with bulimia. Many of these confessional memoirs, which continue to flood the marketplace, are abysmally written; others are packed with exaggerations and outright fabrications. The memoir doesn't get much respect and why should it? Starting sometime in the 1990s, just about every American and her hamster decided to publish an account of their wretched childhood, witchy socialite stepmother, alcoholic homeless father, or struggles with bulimia. Many of these confessional memoirs, which continue to flood the marketplace, are abysmally written; others are packed with exaggerations and outright fabrications.

But there's a simple way to weed out the handful of memoirs worth reading. Just as you wouldn't let anyone remove your appendix or even trim your bangs without checking their credentials, consider exercising similar discretion: Stick to memoirs by proven writers. (Frank McCourt was the exception that proves the rule.) Want to narrow things down further? Seek out memoirs by journalists men and women who are trained, by profession, to glance up from their navels now and then, check their facts, and write with economy and wit. Some of the best recent memoirs are the work of journalists. Elizabeth Gilbert wrote for GQ before publishing her blockbuster Eat, Pray, Love. David Sheff spent years as a magazine reporter before writing his shattering, elegant Beautiful Boy, the account of his son's devastating addiction to methamphetamines. And in Apples and Oranges, Marie Brenner approaches her stormy relationship with her older brother, a cantankerous right-wing apple farmer, like the Vanity Fair correspondent that she is, taking notes on their fraught conversations, sifting through family archives for clues about their longtime rivalry, struggling to corroborate and flesh out her own hazy perceptions and memories.

But there may be no memoirist who has more skillfully used journalistic tools to reconstruct his own life than New York Times media columnist David Carr in his remarkable and harrowing book, The Night of the Gun. Carr takes as a given that our memories are suspect, compromised by the understandable desire to make a coherent story from shapeless experience, to cast ourselves in the role of hero (or dashing villain), and to inject a bit of drama when the plot begins to sag. (Remember James Frey undergoing that root canal without anesthetic?)

So Carr decides to report the story of his life as if he's writing for a newspaper. A drunk and a cocaine addict throughout most of the 1980s, Carr weighs his own murky, drug-addled recollections with those of former friends, wronged lovers, embittered bosses, rehab counselors, and neutral onlookers. ''I would call a long-lost person, set up a time,'' Carr writes. ''I would engage in small talk and then point to some huge scab from the past. 'Do you mind tearing that off?' It was a profoundly embarrassing exercise, but it brought with it no small number of epiphanies.''

The epiphanies are fascinating, and the scabs gnarly. A child of a warm Catholic family in suburban Minneapolis, Carr (refreshingly) blames nothing on his upbringing: ''My home was a good one, my parents were wonderful, no one slipped me a Mickey, and if they did, I would have grabbed it with both hands and asked for more.'' His description of the allure of intoxication is as good as any I've ever read: ''When chemicals and karma combusted into bliss, it was mad, mad fun.''

For Carr, the road to near-ruin begins with booze, winds its way to cocaine, then crack, and finally dead-ends with injected cocaine. After each degrading twist, you expect him to bottom out and turn his life around but he just hits the gas. The low point of Carr's addiction may be when he hands his pregnant girlfriend a crack pipe, and her water breaks. His twin daughters, born hours later, together weighed less than six pounds. You'd expect that the arrival of these two innocent babes would force Carr to quickly clean up, right? Carr initially remembers it that way. But his reporting proves otherwise. According to accounts of friends and official records, six months after his daughters' birth he was still using drugs, and one night left the infants sleeping in his car while he paid a visit to a local drug house.

Even when Carr does eventually enter rehab and make good, his tale veers unnervingly from the familiar and reassuring arc of the recovery narrative. Maybe that's what happens when you stick to the facts. Carr is as immoderate in his drive to unearth every detail of his sordid past as he once was to hoover up that last grain of coke on the floor. You may not forgive Carr his flamboyant misdeeds as readily as he seems to forgive himself, all the while patting himself on the back for his brutal honesty. But he is an undeniably brilliant and dogged journalist, and he's written an unforgettable memoir.

This review first appeared in Entertainment Weekly.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |