Going with the Flow

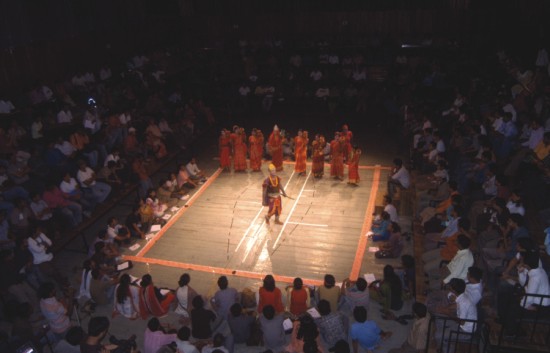

Just how aesthetically rich indigenous performing art forms can be is evident in the performance of Oshtok Gaan, an indigenous theatre form that features the myth of Radha-Krishna. Led by their inspired gayen or lead singer Arun Biswas, they present Nouka Bilash, a part from the medieval legendary poet Baru Chandi Das' masterpiece Sri Krishna Kirtan. The show features Lord Krishna making Radha and her shakhis cross the Jamuna River. But the way it is now presented is significantly different from the medieval masterpiece, rather it is a presentation of the people's epic, adapted, textured and layered through centuries of art rooted in common life. The legends have been presented in a way for mass consumption, yet the energy of the performances manages to effectively conjure the image of Radha-Krishna on the river. Like the master director's best show, the troupe's presentation immensely moves the audience. The mastery of voice modulation of the lead singer and sense of proportion is quite stunning.

Ershad Kamol

Photos: Mumit M

Like the Oshtok Gaan there are hundreds of diversified traditional theatre forms that are still practiced in Bangladesh, something many urbanites do not even know the existence of. Usually, traditional theatre forms are presented in music-dance-drama form and include one or more of the following elements: dance, music and narratives or dialogue. Traditional theatre is always geared towards the masses, created and supported by them and not by the ruling class. Indigenous theatre presentations do not have the refinement of urban theatre presentations; the beauty of an indigenous theatre presentation is in it's spontaneity and the art of improvisation. In indigenous theatre, the performers include actors, dancers, singers and instrumentalists.

According to theatre experts there are about 400 existing traditional art forms, each with distinctive features, and are still performed in different corners of the country. Rural artistes express their indigenous theological beliefs, geographical experiences, social and political views, expectations and dreams through these theatre forms. Theatre represents their respective regions and lifestyle.

Killing of Mahishashur of Hindu mythology has been presented through Hajong ritualistic performance at the festival.

Recently, urban dwellers had the rare chance to experience the vibrancy of such performances thanks to a theatre festival organised by the Department of Theatre and Film of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. The weeklong festival at the Experimental Theatre Stage that ran from April 23 to 29, featured seven troupes from different corners of the country.

The aim of the programme was to give a taste of this remarkable theatre form to urban theatre lovers and the younger generations of theatre practitioners. The arrangement is praiseworthy in terms of time and value of art, since many people these days have little or no idea about the rich tradition of our theatre forms. Most theatre enthusiasts understand 'theatre' as practiced in urban areas, which was introduced in the subcontinent by Lebedev in 1795 during the British colonial period.

The traditional artists who had come from far off places to attend the festival felt honoured that a government organisation had invited them to perform, a clear recognition of their age-old art. A workshop was part of this festival in which young, urban theatre practitioners could evaluate traditional theatre forms in their own way. A photography exhibition had images of other traditional art forms such as Gazir Gaan, Shongpala, Alkaap Gaan, Kissa Gaan, Manikpirer Gaan, Kushan Gaan and Royani Gaan staged at the Indigenous Theatre Festival 2007, organised by the academy.

Most of the performances had been drastically cut down to about two hours - usually they can go on the whole night - to suit the taste of urban audiences. Of the traditional theatre forms performed in the festival only "Mahishashur Badh" represented the tradition of the Hajong community. All the other art forms are Bengali traditions.

Urbanites had the rare opportunity of watching traditional theatre forms almost as they are presented on Ashoon (distinctive performance space) in the rural areas.

The "Mahishashur Badh" is a part of typical Hajong rituals known as the 'Bhuinmapa Hiljaga' ritual, which, in fact, is a kind of travelling performance. Though the performance features a well-known Hindu myth: The killing of Mahishashur by Goddess Durga, it has the kinetic strength of a travelling theatre. The language used however, was Bangla.

Other ritual based performance staged at the festival was "Noukabilash" in Oshtak Gaan form, which is performed as a part of Shib (Shiva) puja at the 'Chaitra Sangkranti', celebrating the last day of the Bangla year.

Ritual is an important element of many indigenous theatre forms. |

"Gujra Satir Banobash" was a narrative that features the king of Kharvan. Despite his endless riches, he wants to drown himself in the river Jamuna because he has no heir. This type of performance is called as "Mati Khoncha Gaan" in Northern areas. On the other hand the myth of Behula-Lakhindar was presented in "Behular Nachari". The performance was highly influenced by "Shongjatra", a popular traditional theatre form of Tangail region.

One of the criticisms of the festival was the inclusion of three jatra performances -- "Tajul Badshah", "Imam Jatra" and "Shonir Chakranto". Dr. Israfil Shaheen, a professor of the Department of Theatre and Music of the University of Dhaka, who was also one of the members of the selection committee members of the festival says, "I don't find any logic of including three jatra forms in a festival, since last year Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy organised another festival exclusively on jatra. They could have included other theatre forms instead of including three jatra forms. And I did not enjoy the amateurish performance of these shows."

"In fact, the committee should select a few forms to be included for an indigenous theatre festival. After selecting the forms a committee including the experts should travel the country to select the authentic troupes. That will enrich the arrangement of Shilpakala Academy."

Shilpakala Academy officials defend themselves by saying that fund constraints have prevented them from arranging such a festival. "With the limited budget it's quite impossible to organise a festival as per the demand of the experts. But, I'm quite satisfied with the arrangement, since the younger urban theatre practitioners got the chance to watch diversified traditional art forms of Bangladesh", says, Golam Sarwar, deputy director, Department of Theatre and Film of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy.

Typically, most artists of traditional theatre are from marginalised classes. They are usually peasants, small traders, vendors, cobblers etc. Traditional theatre pays very little and artistes are forced to take on other professions for sheer survival.

For Shova Mohanto, the lead singer of Shundarganj Palagaaner Akhra from Gaibandha that staged Gujra Satir Banobash> at the festival, theatre is a tradition handed down from his father. For 30 years he has been performing Mati Khonchar Gaan and other traditional art forms of the North Bengal belt. "I believe my performance is not similar to my father's, my mentor", continues Shova Mohanto, "I'm teaching the artistes to perform, most of whom are small businessmen. In fact, no one can take art as the only source of bread and butter in the poor areas. So, one has to have another profession. Art is a kind of entertainment to me, but to my ancestors it was like a religion.”

Apart from the financial hardships that do not allow performers to devote themselves exclusively to the art there are constant demands for cheap entertainment from an audience increasingly influenced by satellite television as well as the Dhalliwood cinema. To attract these viewers, traditional artistes try to cater to the demand for such cheap entertainment. Dr. Afsar Ahmed, a professor of the Department of Drama and Dramatics of Jahangirnagar University, says, "Undoubtedly the performance of <>Behular Nachari<> at the festival was stunning in terms of acting. But, the gestures of the actors appeared to me highly influenced by the satellite culture."

Because of ignorance they even distorted the beauty of traditional theatre by using a live snake on the stage, says Professor Afsar, "To me it was like a gimmick just to draw attention, however, broke the illusion of the audience. And a few people felt disturbed at the presence of a live snake on the stage. And again in the performance of Noukabilash, the actor enacting the character of a shakhi of Radha improvises that she has kept a kori (money) to watch film. Can you imagine a companion of a legend making such a statement? But the artistes improvise in this way, according to the demand of the time. This phenomenon of 'evolution' is universal in case of orally transmitted art forms"

Distortion of art forms is not a crisis only in this region; rather it is a global problem. According to renowned American artistic designer Richard Scechner, 'world theatre' is now in turmoil as it is seen as marginalised, outmoded or elitist since it fails to compete with film or TV or the global distribution of the Internet. The domain of 'theatre' shrinks drastically both in terms of numbers and in terms of importance. In terms of sheer numbers, no individual theatre work can attract even a tiny fraction of the audience constantly guzzling tons of junk available in the Internet and via the mass media.

Traditional theatre forms, however, have always faced the onslaught of religious and cultural diffusion.

The use of 'Chhokras' (males in female attires) to create humour during the shows have become a common element of these performances.

"This kind of cheap entertainment decreases the grandeur of the performance such as Gazir Gaan and Manosha Mangol which are based on legends," says Afsar Ahmed. "In fact, these indigenous performances are interwoven with the traditional rituals of the region. However, the presentation of the artistes is secular" he adds.

He further says, "First of all one should analyse whether any element of the performance is imposed or not. If it is imposed then it distorts the art. Say for example, many elements of cheap entertainment based performance such as Ghatu Gaan should not be labelled as 'obscene' or 'vulgar', but if similar elements are included in Gazir Gaan or Royani or Kushan Gaan these elements decrease the grandeur of the performance. In that case anybody can claim it vulgar, depending on the approach and gesture of the artistes."

Ideological-religious conflict is another factor that 'forces' the artistes to modify the art forms. In indigenous performing art forms, doctrines of any particular religion are not a 'focused' issue. Myths from Hinduism or Islam appear in the presentation just as the 'body', but the intention is secular and for the welfare of humanity. Professor Afsar says, "If we analyse the Bandana of these forms, we find that the lead singer's own religion has no impact during his performance. He pays respect to both Hindu, Muslim and even animist deities. And these religious beliefs are blended in the presentation. But, in the time when fundamental forces are active in the society, traditional artistes are modifying their presentations.”

The traditional theatre forms of Bengal have been distinctive for a thousand years. The earliest evidence of performance in the region is dated back to the pre Buddhist era. The indigenous performing art form of Bengal is included in Bharat's Natyashastra (a Sanskrit treatise on theatre ascribed to Aryan theoretician Bharat. There is a divergence of opinion of period of writing Natyashastra. Some experts says it was written in 200 BC, while some say 100 AD) as Odro-Magodhi form, which is not restricted to dialogue in prose but is rather comprehensive and wide-ranging. However, aristocrat Bharat did not give an elaborate description of Odro-Magodhi form performed by the marginalised class, rather just mentioned it as a distinctive theatre form. But, traditional theatre form of this part of the world has been elaborately presented in Jatak Katha, a collection of Buddhist tales about moral values and nice Behaviour written in 300 B.C, though the Buddhist tales ordered the followers not to practice it.

The Karbala tragedy is also one of the themes of some traditional theatre forms.

Traditional theatre forms however, have always faced the onslaught of religious and cultural diffusion, for thousands of years. The forms were highly affected by the Turkish invasion and later by the British colonial rule. During the British rule, these forms have not been recognised, rather the ruling class imposed western theatre forms in Bengal in the name of making the natives 'civilised'.

But like other orally transmitted forms, the traditional theatre forms have no fixed script; improvisations by the artists during the performance has created room to incorporate new elements infused by the cultural influences of the times. The potential of absorption of alien elements into the traditional theatre forms have saved these from extinction.

The oral tradition of this art of course, makes documentation all the more difficult thus almost similar art forms have different 'titles' in different dialects. For instance, the story of Ramayana-based presentations have different names in different places such as Ramer Panchali, Ramjatra, Kushan Gaan and Ramlila. And the story of goddess Monosha is performed in distinctive styles having different titles in different parts of the country: Royani Gaan in Barisal region, Bishorar Gaan in Dinajpur area, Bhashan Jatra in the middle part of the country and others.

Depending on the taste of the audience the lead narrator presents the same performance in different ways, as above 40% of the elements of a performance are improvised. So, no written documentation can be labelled as the only 'authentic' presentation of any form.

The question therefore remains: Can we preserve our traditional art forms in the era of satellite television and the growing demand for cheap entertainment? Announcing the traditional Kabuki artistes as living heritage, the Japanese government tried to preserve the authenticity of the art form. But how successful they have been, is always a controversial issue. Many believe that we should not interfere with the artists and art forms. At best we can create opportunities for the artists to practice traditional art forms. In that case the government should take effective steps immediately. Moreover, the existing traditional art forms should be preserved audio-visually to have the proper documentation of these ancient art forms.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009