|

Neighbours - Blood in the Red Corridor

Blood in the Red Corridor

The sight of Indians voting may move outsiders to lyricism, but democracy here is limited, and violence begins to appeal

Kapil Komireddi

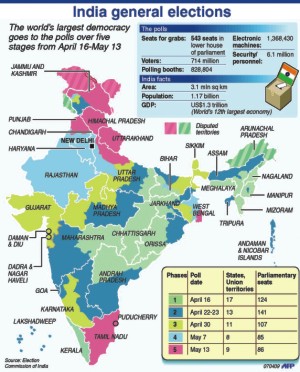

As millions of voters queued up in searing heat on Thursday to cast their votes in the first of the five-phase general election in India, across the region referred to as the "red corridor", armed insurgents detonated landmines, attacked polling booths, shot at police guards and civilians, seized several electronic voting machines and kidnapped at least three election officials. By the time the polls closed, in places that rarely appear in the news media of a west besotted with the "new India" of wealth and glamour, 19 people had been killed. Western reporters preparing platitudinous prelections about the world's largest democracy were forced to alter their scripts at the last minute. As millions of voters queued up in searing heat on Thursday to cast their votes in the first of the five-phase general election in India, across the region referred to as the "red corridor", armed insurgents detonated landmines, attacked polling booths, shot at police guards and civilians, seized several electronic voting machines and kidnapped at least three election officials. By the time the polls closed, in places that rarely appear in the news media of a west besotted with the "new India" of wealth and glamour, 19 people had been killed. Western reporters preparing platitudinous prelections about the world's largest democracy were forced to alter their scripts at the last minute.

Following last year's attacks in Mumbai, security was cast as a key issue in this election. But the source of Thursday's violence was not the familiar brand of militant Islam. Rather, it emanated from the frustrations induced by the brutality and venality of the Indian state, which justifies its worst excesses against those resisting its intrusions by invoking the legitimacy the democratic process has conferred on it.

Armed Marxist revolutionaries known as Naxalites named after the 1967 revolt by farmers in the West Bengal village of Naxalbari control the "red corridor" which spreads across some of India's poorest states. In the last decade alone, people in these regions were subjected to extraordinary injustices by the Indian state: their resources were depleted to fuel urban India's growth; their farmlands were forcefully appropriated and reassigned to wealthy corporations; and their protests were actively suppressed by India's ruling elite.

In 2007, as foreign dignitaries, including German chancellor Angela Merkel and former US treasury secretary Henry Paulson, descended on New Delhi to attend yet another conference on India's rise, thousands of tribal peasants and landless famers from 15 Indian states marched to the capital to register their peaceful protest and demand land rights. The rally's chief organiser, the Gandhian PV Rajgopal, described it as an unprecedented event. "Non-violent direct action has never been tried so effectively," he claimed. "These people are living, walking and sleeping on highways since we set out." But as soon as they arrived in Delhi, having walked over 600km to get there, they were herded into a roofless enclosure by the police and locked up for the rest of the day without any access to toilets or drinking water.

Contrast this with the outrage that was provoked just the previous year when Luxembourg attempted to thwart the Britain-based billionaire Lakshmi Mittal's bid to acquire Arcelor. Newspapers, television networks, columnists, businesspeople and politicians united to condemn Luxembourg. India's commerce minister, Kalam Nath, denounced European "discrimination" and Manmohan Singh, the prime minister, personally took up the matter with Jacques Chirac. Mittal got Arcelor, and there were loud celebrations in New Delhi. But in their collective mission to aid a fellow Indian who had been slighted by foreigners, indignant Indians seemed to put aside the fact that, other than his passport, Mittal has had little to do with India.

India today is home to the largest pool of the world's poorest people, but this reality is carefully concealed in the new narrative of "superpower India" that is aggressively promoted by its tiny elite. This myth is so heady that an expatriate billionaire's bid to acquire a foreign company makes the headlines, occupies the airwaves and keeps the prime minister awake at nights. But the physical detention of more than 25,000 protesters in the scorching heat of Delhi barely scratches the conscience of first-world India. India today is home to the largest pool of the world's poorest people, but this reality is carefully concealed in the new narrative of "superpower India" that is aggressively promoted by its tiny elite. This myth is so heady that an expatriate billionaire's bid to acquire a foreign company makes the headlines, occupies the airwaves and keeps the prime minister awake at nights. But the physical detention of more than 25,000 protesters in the scorching heat of Delhi barely scratches the conscience of first-world India.

This delusion-fuelled triumphalism is precisely what Indian voters rejected in 2004. But the incumbent Congress-led government, which came to power on the promise of "inclusive growth", has proved itself an even greater failure.

The quinquennial sight of impoverished people casting their votes may move some to lyricism. But thanks to India's uniformly third-rate politicians, to a vast majority of Indians who actually live here, democracy means very little besides voting. As Jaideep Sahni has observed, electoral regularity seems to be the limit of Indian democracy. But these Indians impoverished, abused and ignored must not be taken for granted: they have brought down harsher adversaries and destroyed stronger structures.

As the Delhi protesters dispersed that evening, having endured the humiliations first-world Indians inflicted on them, they looked firm in their conviction about the futility of non-violent struggle in making their voices heard. They looked ready for conscription into the Naxal forces. And they or people like them struck as India went to the polls.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |