|

Tribute

Gaziul Haque

and those beautiful times

Syed Badrul Ahsan

It was in the early 1970s, soon after the liberation of Bangladesh, that I first spotted Gaziul Haque. He

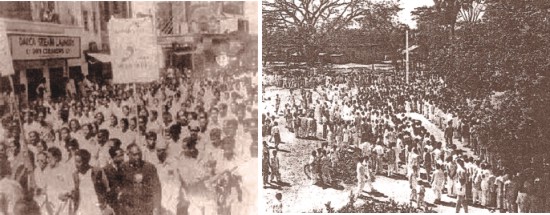

Bhasha Shoinik Gaziul Haque |

was leaning on the balcony of a house in Malibagh, looking out on to the street below. It was the road that had at one end Mouchak market and at the other the under-construction Bangladesh Television centre in Rampura. As a newly enrolled student at Notre Dame College, I walked past that house everyday, which is to say that it was often that I saw Gaziul Haque, wearing a smile that highlighted the radiance in his bearings, on that balcony. I knew he was an important man, that he had something to do with politics. But it was the details that I did not know, those that related to his association with the Language Movement of 1952. And I did not have the courage to go and talk to him about it. A college student had no business walking up to a famous individual and asking him questions about the reasons behind his fame.

And so the years passed. I went on hearing about Gaziul Haque in the newspapers, reading about him and reading what he had to say about politics and culture. It was not until the early 1990s, though, that I actually came in touch with him. And that was when Sheikh Hasina, then leader of the opposition in the Jatiyo Sangsad, decided that the newly set up Bangabandhu Memorial Museum needed to have its various sections lined with photographs relating to the crucial moments in Bangabandhu's life. A committee was formed and on that committee Gaziul Haque and I were members. There were some other individuals there as well. Over a number of weeks stretching into quite a few months, we sifted through the innumerable albums that bore diverse images of Bangabandhu and his family. We would sit in Bangabandhu's library; and then there were the times when we pored over the photographs in the room where Sheikh Kamal once lived. Those were sad moments, for none of us could brush away, even for a moment, the thought that in that very house the Father of the Nation and much of his family had lost their lives at the hands of a murderous group of soldiers.

It was in those moments that Gaziul Haque took us all back to the past, relating to us stories of a young Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, of his courage and consistent conviction in the face of adversity. Having been a young man in the early 1950s, Haque remembered the events that had shaped the Language Movement and would give us graphic details of the incidents which led to the seminal happening of February 21, 1952. And then of course there were the anecdotes Gaziul Haque came up with, tales that gave us a little more insight into the lives of such illustrious Bengalis as Sher-e-Bangla, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Moulana Bhashani. A particular trait in Haque was his clear staying away from speaking ill of anyone. He did not carp; and it was not in him to denigrate anyone who has had a hand in the making of Bangladesh's history.

If you ask me what it is that makes me remember Gaziul Haque, apart from all his other attributes, I can tell you, simply and surely, that it was his abundant sense of humour. Being in his company was an experience in the gathering of joy. He laughed uproariously manner. It was, as they say, infectious laughter. Even the most sombre among us could not fail to be affected by his good cheer. It was the raconteur that worked in him. You could say that every time Gaziul Haque entered the room, he filled it with his presence. He cracked jokes as he dipped that biscuit in his tea before placing it in his mouth. And he did all this even as he worked on the documents and photographs that lay before us as part of the programme to inject dynamism and vigour in the Bangabandhu Museum.

Gaziul Haque was deeply committed to secular politics. It was a conviction that took root in him in his youth and rippled out into an ever-widening sphere in his adulthood. Unlike so many others, he was not, in the days that I knew him, disheartened by what was being done to Bangladesh by those who had yanked the country away from its liberal political moorings. It was always his belief that a better tomorrow would dawn, that we as a people would find the path back to the principles which had led us to freedom through the darkness of 1971.

Source: File Photo

The passing of Gaziul Haque is for all of us a renewed awakening of consciousness about the contributions of an iconic generation to the forging of national liberty. That generation now slowly makes it way into the twilight, taking with it its free spirit, its abundant laughter, its priceless humour and the moral principles on which it lived life. Its transition to the world beyond the grave leaves us that much poorer.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |