Writing the Wrong

After The All Clear

Sharbari Ahmed

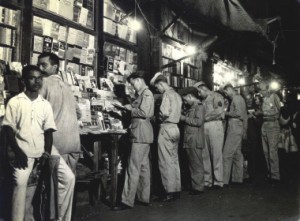

This was a fine time to tell me this. Huddled under the stairs at the Metro picture hall, while Japs dropped bombs. I saw the poster with Gable leaning over Leigh light up as a bomb hit its mark across the street and blast a gash down the centre of it, shattering Das' store front. It made Gable's smile sinister. This was a fine time to tell me this. Huddled under the stairs at the Metro picture hall, while Japs dropped bombs. I saw the poster with Gable leaning over Leigh light up as a bomb hit its mark across the street and blast a gash down the centre of it, shattering Das' store front. It made Gable's smile sinister.

“I'm pregnant,” she said.

I shrugged. Like a boy would, actually like the indifferent boy who had gotten her into this state would, only I am not a boy, I am a grown woman and this girl--woman--is my responsibility. (This is how I react when I am utterly at sea. Calmly, and coldly. It works most of the time. I mean I can fool people into thinking I am in control.) Oof! I wanted to say. Patience, not now. Not now!

I didn't say it but she heard it anyway.

“What the crikey do you want me to do? How long can I hide it?” she said. “Now's a good a time as any.”

“Don't be morbid,” Asma said. She was also huddled with us, with her plump hands clamped over her ears most of the time.

“How's this morbid?” Patience demanded. “We might die, I feel the need to confess.”

“Yes, yes, you are being pragmatic again,” I said and sighed.

Patience's jaw was tight and stubborn. “Yes. I need to be in these uncertain, dull times,” she said.

Patience found the war extremely boring. It interfered with her fantasy of running off to Hollywood and ousting Merle Oberon from her throne as the Queen of Exotic Movie Stars With Enigmatic Parentage and Intriguing Accents. She had had a plan and it had all gone to the dogs because that short Austrian and his equally diminutive and intense Jap cohorts had decided to invade Poland and now China. India might be soon to follow. What then? No Hollywood for Patience and deprivation for us. We already felt the pinch and now here we were, under the cramped, musty, rat faeces ridden stairs at our favourite picture hall on Park Street. Oof! Double oof! Damn, damn, damn.

“Patience, we shall discuss, when we return to the club,” I said, again calmly.

“If we return,” Asma said.

“Who's being a morbid miss now?” Patience snapped.

An hour later they gave the All Clear and we emerged from beneath the stairs, blinking and coughing at the dust the bombs had kicked up. I am never the first to emerge, as I never fully trust that everything is clear. I wait. Asma bolts out as fast as her plump body will allow as does Patience. I worry that one of these days they will yell All clear! The girls will bolt out and boom! All that will be left of them are their worn shoes with wisps of smoke coming out of them, like in cartoons. Why do I worry about these silly women? I ask myself almost everyday. And then I answer: well, because, in a way, they belong to me. They are under my obligation and I theirs. They earn for me, keep me in shoe leather so to speak. I never forget that, but it also means, well that I have to bloody well take care of them and as evidenced by Patience's delicate state, they bloody well cannot take care of their bloody selves now can they? An hour later they gave the All Clear and we emerged from beneath the stairs, blinking and coughing at the dust the bombs had kicked up. I am never the first to emerge, as I never fully trust that everything is clear. I wait. Asma bolts out as fast as her plump body will allow as does Patience. I worry that one of these days they will yell All clear! The girls will bolt out and boom! All that will be left of them are their worn shoes with wisps of smoke coming out of them, like in cartoons. Why do I worry about these silly women? I ask myself almost everyday. And then I answer: well, because, in a way, they belong to me. They are under my obligation and I theirs. They earn for me, keep me in shoe leather so to speak. I never forget that, but it also means, well that I have to bloody well take care of them and as evidenced by Patience's delicate state, they bloody well cannot take care of their bloody selves now can they?

All I ask when they come to me is to be clean, as in hygiene--spiritual and emotional cleanliness is entirely their problem--and that they take the necessary precautions to not be in the family way. I provide food, shelter, clothing and medical care for the usual afflictions. Thus far, I have kept up my end of the bargain and thus far, only Asma has kept hers. My other girl, Maha, has been knocked-up as the Americans say, more than once, and now Patience, from whom I expected more sense, would need and want an abortion. Patience was my best singer, and when she wanted to be, dancer. She kept the troops enthralled. I could not afford to lose her.

Everyone walked home slowly, lost in their own thoughts. You would think that people would be in a hell fire rush to get home. I think everyone was dazed. Keep calm and carry on, the government told us and that is what Calcutta did with a vengeance. It was December and pleasant. Christmas was three days away. The Japs started bombing on the 11th of December and would continue doing so well past new year's. Luckily, this time, there was only the one gash down the street, and it was not that deep, perhaps three feet and only five feet wide. It looked as if someone had attempted to dig a trench and gave up halfway through. Das' shop front windows were shattered but other than that and some dust, the street and other buildings were intact. We would later find out that only one soul had lost his life and that was because the bloody fool refused to leave his father's body down by the burning ghats. Well, now he had joined his father. The unlucky sod.

Maha was waiting for us when I got back to the club. She seemed cheerful enough.

“Where were you?” Asma asked them.

“Newmarket,” Maha said. “The shelter nearby is ever so much better than the Metro.”

We had left the club in a hurry, overturning chairs and knocking over glasses. As hard bitten and casual as some of us seemed, it was always in the back of our heads that this day might be the day the Japs hit their mark again and again, like the Luftwaffe did in London on a daily basis. This might be the day the last thing I see is Gable's smile and Leigh's heaving cleavage from underneath the dirty marble stairs at the Metro; Asma whimpering on one side of me, Patience tossing her curls about in that studied Bette Davis way she tries to emulate when she is most afraid. Each day I live through an air raid has made me more confused as to God's plan for me and this feeling of urgency is creeping up, like I am not living the way I should. I keep getting spared. Surely this means something.

Maha handed me a chit of paper when I had settled. I asked Ghosh, the bartender, for a small glass of something. “Surprise me,” I said, as I had no idea what had been purchased on the black market that week. Everything was getting scarce, except rice, but that would happen soon enough, with catastrophic results.

I read the note. It was from a Lt. Edward Lafaver, from the 101st, requesting the pleasure of mine and the girls' company on their base, to ring in the New Year, as only the Americans know how.

I tossed the note away. There were more pressing matters.

“Ghosh, is your uncle still in town?” I asked.

He nodded silently. Ghosh was a hardworking man, frankly frightened by all of us and our “fast” ways. “Well, please summon him today.”

He left at once, again silently.

I turned to look at Patience. Her face was white, all the bravado drained out of her.

“Is it really necessary Yasmine?” she asked me.

I blinked in astonishment. “How can you even ask? You know my policy. Besides, do you even want a baby now?” I shook my head. “If you think he will come rescue you--”

“I have never thought any man would rescue any of us,” Patience cut me off.

“Then?” I asked.

“It seems wrong,” she said. “I was raised a Catholic after all.”

Her lips were whiter than just moments before and I realised she was very serious.

But I said, “You can't be serious Patience.”

Patience, to my amazement and discomfort, began to cry. Maha and Asma immediately rushed to her side and glared at me.

“What, why can't I be serious?” she sobbed. Soon, her lovely golden skin was mottled and snot ran down her nose as she worked herself into a complete state of hysteria, with the help of Maha and Asma, I might add. “We could raise it, together,” she cried. “That was how you were raised, Yasmine. In a house full of strong women, no men in sight to mess about and cause problems.”

“Do you really want to bring another anglo-khalo into the world Patience?” I said, trying to reason with her. “They would have no status, neither here nor there, who would claim them?”

“But things are changing!” Asma chimed in. “Soon India will be independent, Gandhi-ji said so.”

“Well then tell Gandhi-ji to come raise this baby and find the money for bloody nappies and milk,” I snapped. Perhaps it was the stress of the bombs. I knew my anxiety had been building for days.

“When we are well shot of the Brits, you know what will happen to the Anglos? You lot think you are too good for us niggers,” I said, pointedly to Patience. Though we had been friends since childhood, there was always that between us. Her Anglo blood and what it meant. “You call England home! But guess what? They don't want you lot back there either, because back there you are the niggers.”

I shocked myself and shut up. I was contrite, at once, as is the nature of sudden rages. The repentance is immediate and almost always too late. I hated that word, and here I had used it twice in one go. Maha and Asma moved away from Patience and walked upstairs. Neither of them looked at me. We were left alone, both staring at the floor.

“I know you are right,” Patience finally said, in a small voice.

“Do you?” I said, relieved. I was so grateful she even spoke to me.

“Just for a moment I thought, that maybe...oh never mind,” she trailed off.

I took a deep breath. “I know,” I said, though I didn't. I truly could not imagine wanting to bring a child into this insanity.

“You know I'm a dreamer,” Patience said.

“Yes, well you are not the only one. Look at me,” I said. “Dreams are good,” I added, again lying. I had abandoned dreams a long while back. The only thing that made sense was work. And the storing and acquisition of money.

Ghosh came into the room. “My uncle is here, Yasmine Didi,” he said diffidently.

“That was quick,” Patience said. She looked frightened.

“He was nearby, as luck would have it,” Ghosh said. He smiled sadly at us. “Das was hurt a bit and his son needed stitches.”

I nodded at him. “Okay. Patience?”

She shuddered and nodded her assent. I went to her and held her loosely. Ghosh's uncle came into the room. He was an elderly man, with rheumy eyes, and paper-thin skin. This is unreasonable, I know, but these kinds of doctors who are willing to do these kinds of things seem to have an air of corruption about them. But if we had encountered him on the street, not knowing what he did, he would have looked like any kindly old uncle, who always had toffees in his pockets for his brother's children. Patience looked at him with recrimination. I think I did too. None of us were thinking clearly.

“Upstairs,” I said.

“Show time,” Patience said, trying to smile at me. She followed the men up the stairs.

God forgive me, I said under my breath. I called to a bearer, who was loitering close by, “boil some water!” and poured myself another glass of black market something or other.

(An excerpt from the novel in progress Bombay Duck)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |