Tribute Tribute

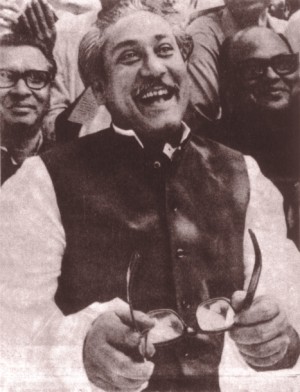

The statesman in

Bangabandhu

Syed Badrul Ahsan

There was a remarkable statesman in Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. An early instance of it came in January 1972 as he addressed the world's media in London only hours after his arrival from incarceration in Pakistan. He bore no ill will toward Pakistan, he said, and he wished President Bhutto well. It was a sentiment he would restate in Dhaka a couple of days later, when he told a rapturous crowd that he was happy with his Bangladesh and he expected Pakistan's new leader to be content with what remained of his country. For a political leader who had been in solitary confinement in an undisclosed location in Pakistan for nine months even as his people were being put to the sword and the gun in an unprecedented genocide, it was remarkable restraint on his part. Nowhere was there in him any sign of retribution. It was proof once again of the qualities that had raised him to the peaks over the years.

And yet there was firmness, a huge degree of it, when it came to Bangabandhu's defence of the national interest before the global community. In 1973, when at a meeting with him Nigeria's military leader Yakubu Gowon grumbled that had Bangladesh not broken away from Pakistan, the old country would have remained a solid bulwark for Muslims everywhere, Bangabandhu cut him short, gently and ever so emphatically. “Mr. President”, he told Gowon, “if we had remained in Pakistan, it would be a strong country. Again, if India had not been divided in 1947, it would be an even stronger country. But, then, Mr. President, in life do we always get what we desire?” Gowon said no more. Again, at a session with Saudi Arabia's King Faisal in the early 1970s, the Father of the Nation was visibly rattled when the monarch implied that Bangladesh's emergence as a secular entity had weakened the Islamic world. He calmly and firmly asked Faisal where the Islamic world was when millions of Bengali Muslims were being butchered by the Pakistan army in the name of Islam. Faisal fell silent.

Bangabandhu's statesmanship was quite removed from the pretence and hypocrisy which generally characterised diplomacy in the modern world. He was polite in dealing with the leaders of other nations and yet he remained keenly aware of what he needed to tell them about his people and their travails. On his way home back to Bangladesh in January 1972 through Delhi, he rather surprised Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by asking her when she would withdraw her soldiers from Bangladesh. By March 17, Bangabandhu's birthday, India began taking its soldiers back home. There may have been little subtlety in Bangabandhu's approach, but there was no mistaking his awareness of the national interest. And the national interest was clearly a prime factor in his decision to let the 195 Pakistani military officers accused of war crimes in Bangladesh in 1971 go free. There were many who excoriated him over his move, but he saw it from a particular point of view: that the Bengalis stranded in Pakistan would plunge into grave problems if the Pakistani soldiers were not freed. Besides, there was a core philosophy at work in his approach to foreign policy. He had made it clear that for Bangladesh, foreign policy would be based on friendship with all and malice toward none. Bangabandhu's statesmanship was quite removed from the pretence and hypocrisy which generally characterised diplomacy in the modern world. He was polite in dealing with the leaders of other nations and yet he remained keenly aware of what he needed to tell them about his people and their travails. On his way home back to Bangladesh in January 1972 through Delhi, he rather surprised Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by asking her when she would withdraw her soldiers from Bangladesh. By March 17, Bangabandhu's birthday, India began taking its soldiers back home. There may have been little subtlety in Bangabandhu's approach, but there was no mistaking his awareness of the national interest. And the national interest was clearly a prime factor in his decision to let the 195 Pakistani military officers accused of war crimes in Bangladesh in 1971 go free. There were many who excoriated him over his move, but he saw it from a particular point of view: that the Bengalis stranded in Pakistan would plunge into grave problems if the Pakistani soldiers were not freed. Besides, there was a core philosophy at work in his approach to foreign policy. He had made it clear that for Bangladesh, foreign policy would be based on friendship with all and malice toward none.

Pragmatism was a huge motivational factor in Bangabandhu's attitude to the United States and China. Both these countries, insofar as their governments were concerned, had overtly opposed Bangladesh's war of liberation and had publicly upheld Pakistan's cause in 1971. The Chinese made their pro-Pakistan attitude clearer when, after December 1971, they twice vetoed Bangladesh's attempt to enter the United Nations. And yet Sheikh Mujibur Rahman exercised restraint, saying not a word against Washington and Beijing. He knew he would need to deal with them in future. It was a classic case of a national leader forgiving the sins of people he needed to turn into friends. Bangabandhu travelled to New York and then to Washington, where he apprised President Gerald Ford in unambiguous manner of the difficulties his country was up against. He spoke to Henry Kissinger, who would later visit Dhaka, despite knowing that Kissinger's had been a strident voice in the Nixon administration's tilt toward Pakistan in 1971.

In his brief administration of slightly over three years, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was instrumental in taking his new country into the important councils of global diplomacy. It was his sheer force of personality, his charisma, that earned Bangladesh's people respect and sympathy across the world. There clearly was the perception in him that while Bengalis inhabited a small state, they were privy to a culture that was as spacious as the long distances of time between generations. Which was why they needed to make themselves heard among other nations. Bangabandhu personified this ambition in his people, through choosing to join the summit of Islamic nations in Lahore in February 1974 once Pakistan had acknowledged Bangladesh as an independent nation.

Bangabandhu was a larger than life individual. Edward Heath and Harold Wilson were happy in his company. Fidel Castro was mesmerised by him, by the fact that a nation had fought and won a war in his name even as he languished in prison. Muammar Gaddafi, Pakistan's friend, was awed by Bangladesh's leader. Marshal Tito respected him hugely and Anwar Sadat thought of him as a brother. The United Arab Emirates' Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al Nahiyan was cheered at the discovery that he and Mujib were both sheikhs. Bangabandhu grinned and told him, “Yes, but there is a difference. You see, I am a very poor sheikh.” Both men burst into laughter.

There was the quintessential diplomat in Bangabandhu; and it was in evidence as far back as the heady days of early 1972. Asked by a newsman if he contemplated West Bengal someday joining his free country to create a greater Bangladesh, he smiled, blew a puff of smoke from his ubiquitous pipe and said gently, “I am happy with my Bangladesh.”

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |