Impressions

A Roth Stands Still in Dhamrai

Shakil Rabbi

It was late afternoon when we got to Dhamrai. The seven of us-a group of Dhaka University friends-took a regular-route bus up to stay the weekend at Ishtiaque's place. It was a hot day and we baked in the heat as the tin-can bus roughed north through the highway. Even with the discomforts, I soon got lost watching the scenery: the congested morass of crowded roads and large makeshift buildings slowly gave way to a muddle of corrugated-tin shacks, large shining factories, and dirty little buildings. Then Dhaka completely ebbed away somewhere after Savar and the landscape became an expanse of green fields, with intermittent swathes of Kaashful, growing wild and looking like sprinkled powdered white sugar upon the otherwise deep green. It was late afternoon when we got to Dhamrai. The seven of us-a group of Dhaka University friends-took a regular-route bus up to stay the weekend at Ishtiaque's place. It was a hot day and we baked in the heat as the tin-can bus roughed north through the highway. Even with the discomforts, I soon got lost watching the scenery: the congested morass of crowded roads and large makeshift buildings slowly gave way to a muddle of corrugated-tin shacks, large shining factories, and dirty little buildings. Then Dhaka completely ebbed away somewhere after Savar and the landscape became an expanse of green fields, with intermittent swathes of Kaashful, growing wild and looking like sprinkled powdered white sugar upon the otherwise deep green.

We got down at Dullibhita and took a rickshaw the rest of the way to Dhamrai Bazaar. Ishtiaque's house was right on the bazaar street but was still quiet compared to a Dhaka neighbourhood. It was three stories tall and from the roof one could see an unbroken horizon of the entire union.

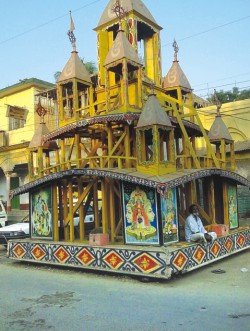

Despite the burning sunshine earlier, it was raining heavily around four o'clock. But then it lightened to a drizzle; and we decided it was good enough to explore the bazaar and the villages. However, the bazaar road remained relatively empty because it was still very wet. Hawkers and shops were open and peddling, yet most people were sitting in hotels and sweet shops or huddled under plastic tarps and doorways, keeping out of the rain. The drains were blocked by cakes of mud and scum, and black pools collected in the corners. I could see the famous yellow Roth of Dhamrai standing tall at the far end of the road; its bright colour stuck out against the drab grey day. Images of it fully ornate being dragged flashed in my mind, but then the pictures disappeared and I saw it standing there, gutted and still.

I spotted a troop of monkeys sitting in the hollow of the roof of a store. The males sat affectedly with fat bellies, looking like Zamindars surveying their lands; the females were smaller, and each carried an infant in its breast. The infants were thin and scruffy, looked like large brown rats.

Ishtiaque explained that the monkeys lived in town. There used to be a lot of them in the local areas. But as people cut down the trees they moved into towns like refugees from a lost country. Dhamrai used to be predominantly Hindu but more and more Muslims moved in after partition and then independence. Monkeys are not the children of Hanuman to a Muslim. So the primates, losing their privileged status found the world more indifferent, and gradually gave ground in the scrap for survival.

According to Ishtiaque the monkeys behave just like people. One of them was once shot by an eccentric old man who lived on the street. The troop carried the wounded member (only slightly hurt) to a doctor- they even knew where to go. Afterwards they came back regularly to pick up medicine from the guy.

I had heard that in certain parts of the country, monkey troops act like the neighbourhood goondas; they decide who comes into their territory and who does not. They take tributes from the people, and attack any who resist. I mused that people might actually prefer the primate thugs to their human equivalents.

The rain let up a little by then, and so we decided to take a pair of rickshaw-vans and go further into the countryside. I had never seen a rickshaw-van before; they were made of box-frames strapped to the front end of a rickshaw, with two cushioned planks legoed in over the frame as seats. Four could sit in the back, perilously uncomfortable; the seats shifted as the rickshaw-van moved.

As we rode, Ishtiaque pointed out a large old-style white house with green panel windows; it was the famous 'made in Bangladesh' house, where they made the famous brass pieces. Little goldsmith stores and metal works lined the sides of the area roads; brightly colored posters of Hindu gods were taped up on walls. I knew that Dhamrai is famous for being the center of Bangladesh's antique trade and it showed: rows of stores displayed art and utensils, exquisitely made and weighted with the unmistakable air of age.

We got off the rickshaw-van when it went over the Bongsha river bridge; the road became too steep. I was glad to get off; it was too uncomfortable for me to be able to look around. The two pictures of the Bongsha one got from the bridge were worlds apart. On the left, the river had atrophied to a thin sliver; there were mounds of sand piled upon the banks; dredgers and boats rested aground on steep inclines. The other side was healthier, the bank was clear and the breadth was broader. Looking at it, the obvious thought was the 'Save the Rivers' campaign: I had to wonder whether each picture symbolized a different possible future.

We did not get much further though. The rain picked up again and we turned back. We got as far back as the Roth before it became a deluge. The eight of us jumped off the back of the vans and ran into a sweet shop to get out from under the torrent. We took a seat and ordered some tea and sweets, and stayed till nightfall. As we sat there, I looked at the large yellow-metal structure of the Roth: it looked fixed in time and shone like gold in the downpour.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |