|

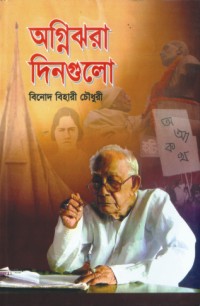

Cover Story

A Long Walk to Freedom

Binod Bihari Chowdhury |

As you enter the narrow lane on Mumin Road, an older part of Chittagong, it is fascinating to note that almost everyone living on the lane, or even running a small shop, is more than happy to help you look for dadu's home. An even narrower gate and you enter rooms under construction, filled with dust and men working. Finally, you find Binod Bihari Chowdhury, a physically diminutive figure crouched up in his bed. The first take of his room overwhelms you with a feeling of pride-- the room showcases several trophies and crests with his name engraved on each one, the walls are filled with photographs of the revolutionaries as illustrious as Mahathma Gandhi, Masterda, Pritilata; the newsmakers in recent times, Nobel Laureate Mohammad Yunus; Bihari's wife Bela Chowdhury who passed away on December 28, 2009.

Elita Karim

Photos: Zahedul i khan

Almost 100, Binod babu, or dadu, as he is affectionately called by his friends, needs lots of rest and cannot be expected to move around much, explains Prabir Chowdhury, a retired school teacher and Binod babu's neighbour, to a university student who has been trying to arrange a reception in his university in Chittagong with Binod babu as the guest of honour. “Ever since his wife passed away, dadu has been physically weak and cannot move around too much,” he says. Bakul, or Bakul mashi as she is known by everyone around, has been taking care of Binod babu and his wife for the last few decades.

Binod Bihari Chowdhury was born in North Bhurshi under the Boalkhali upazila in Chittagong on 10 January, 1911. He is the son of lawyer Kamini Kumar Chowdhury and Bama Chowdhury. Binod had joined Jugantor an underground revolutionary organisation in 1927 and was associated with great revolutionary leaders like Masterda Surjya Sen, Tarokeshwar Dostidar, Madhusudan Dutt and Ramkrishna Bishwas.

Binod babu is all of 99 years and 1 month old, living his 100th year as he speaks to the Daily Star. He seems frail and physically exhausted. However, his eyes light up when he goes back to his teenage years in the 30s, when he joined Masterda Surjya Sen's group of rebels and revolutionaries in Chittagong. A bright student that he was, Masterda did not want Binod to join his group. “He would sit with me and discourage me,” says Binod babu. “He used to say that a scholar like me should not get involved in all this and would try to dissuade me every day. One day I just smiled at him and told him that if Masterda did not take me in, I could go and join any other group, since I read about them in the papers all the time. That was when Masterda agreed to take me in his group.”

As he goes on about the legendary hero of the Chittagong Uprising, Surjya Sen, popularly known as  Masterda, Binod babu looks around himself, as if trying to recollect his memories. The Chittagong Uprising is said to have played a very crucial role in creating awareness amongst all in India to drive the British away and fight for what is rightfully theirs. Binod babu pauses for a while and seems to relive the long gone moments once again that reflect clearly in his eyes. “In 1933... no, let's move slightly behind,” he murmurs. “In 1930, April 18, Chottogram Jubo Bidroho (Chittagong's youth rebel) takes place under the instructions of Masterda. He told us, that the only way we could save our country from the clutches of the British, firstly by seizure of power (khomota dokhol), and secondly by sacrificing our lives for the country (more Masterda, Binod babu looks around himself, as if trying to recollect his memories. The Chittagong Uprising is said to have played a very crucial role in creating awareness amongst all in India to drive the British away and fight for what is rightfully theirs. Binod babu pauses for a while and seems to relive the long gone moments once again that reflect clearly in his eyes. “In 1933... no, let's move slightly behind,” he murmurs. “In 1930, April 18, Chottogram Jubo Bidroho (Chittagong's youth rebel) takes place under the instructions of Masterda. He told us, that the only way we could save our country from the clutches of the British, firstly by seizure of power (khomota dokhol), and secondly by sacrificing our lives for the country (more

The walls of his room are filled with photographs of revolutionaries; above leftis a picture of Masterda. |

more desh ke bachano). Masterda designed a programme where we had more than a hundred young boys and men. We would take Chittagong under our control. Of course, there was a possibility that we would die immediately. And if we were successful in occupying Chittagong, we would probably be able to keep control for hardly a week, until soldiers from all over the country would come and kill us anyway. But we were prepared to die. Through our deaths, we would let our country live. This way we would be able to encourage the youth in our country to rise and fight for their homeland. This way the young people would be able to take back from the British what was rightfully ours. To achieve your goals, sometimes you have to sacrifice, and we were ready to sacrifice our lives.”

It was like reading a history book, only better. Reading about the Chittagong Armoury Raid is one thing; however, listening to the actual happenings from Binod babu himself was like experiencing the revolution itself. “We had two armouries,” says Binod babu. “According to Masterda's programme we took over the telephone and telegraph office. The second agenda was to take over the railway lines running from and to Chittagong and Feni so that soldiers would not be able to reach us. The last agenda in the programme was to blow off the European Club situated in Pahartali, where the British would get together, eat and drink and dance away the nights. We were not allowed there -- Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists nobody could go inside.” At this point, Binod babu pauses for a while and talks of the famous Jalliawala Bagh incident in Punjab, where thousands had gathered to silently protest the British occupation and their treatment of the Indians. On April 13, 1919, the Britsh Indian Army soldiers, under the command of Brigadier-General Dyer had opened fire on an unarmed gathering of men, women and children. The firing lasted for 10-15 minutes until the soldiers ran out of ammunition. Hundreds died brutally when gunned down, while some tried to escape the bullets, jumping inside the well. The walls of the Jalliawala Bagh, to date, bear the bullet marks, as a reminder of the massacre. “We wanted to take revenge for those hundreds and more innocents and blow up the European Club,” he continues. “But that day, was Easter Friday or Good Friday and the British had locked up by 8 pm and left the club. Our boys had gone there at 9 pm and could not complete the mission. Later on, another club was blown apart instead of the European Club, which was situated in the Chittagong Railways area.”

Binod babu points at a picture of a young girl in his room. “Pritilata,” he says. “She had bombed the club at the Railways area.” Died at the age of a mere 20-21 years, Pritilata Waddedar is one of the first woman martyrs in the history of India. “There was another revolutionary, Ramkrishna Bishwas, a brilliant student and a year older than me in school,” says Binod babu. “He was caught and was sentenced to die. Nobody could meet him, not even his relatives. Pritilata heard about Ram Krishna, managed to convince the jail authorities that she was his distant relative and actually met him 40 times, once every week. I think this was possible because the jailer back then was an Irish. And the Irish by nature are freedom lovers and had to fight for their land, just like we did. Anyway, Masterda had heard about Pritilata and wanted her to join the group. Pritilata also was very eager to join our group. We, generally, did not allow girls or women to be a part of our group. However, at one point, we realised that it was impossible to work without girls, so as to achieve our goals and complete our missions. Girls could easily transport weapons, even on local transport. That is why we depended on a lot of women who transported a lot of our weapons from one part of the country to another.”

While updating himself on the current happenings.

Pritilata was young and courageous. She would work with a lot of zeal and was determined to drive the British away. “After completing her Bachelors degree, Pritilata had come to join Masterda's forces,” remembers Binod babu. “One day, the police had surrounded Masterda's shelter where several from the team were also situated. Immediately, Nirmal Sen, another leader of ours, asked Masterda to move downstairs. Through a pathway, Masterda reached a small pond. Along with him were Pritilata and one of the boys from the team who was suffering from high fever. All three of them, hid under water. They would bring their nose up, breathe and then go down again. At one point, a stray bullet hit the boy suffering from fever and killed him. After a couple of hours, when everything had cooled down, Masterda and Pritilata climbed out of the water and found dead bodies all over the place. Nirmal da was also dead. They shifted to another shelter. He asked Priti to change into something else quickly and go to town so that in the morning, the authorities would not suspect her of being involved. But she refused to go. She could not bear the fact that Nirmal da and the boy had died in front of her. Pritilata wanted to work with Masterda and if necessary would take a bullet. Masterda had asked her to wait and would assign her accordingly in a mission. Later on, when the European Club could not be blasted, Pritilata was asked to blow apart the club in the Railways. Masterda had also asked her to take Potassium Cyanide after she completed her mission. Otherwise, she would be tortured when caught (as was inevitable) and Masterda did not want that.”

Still strong in his 100th year.

Binod babu was just a young teenager when he got involved in the revolution. When asked about his schooling, he laughs and says that most of his life was spent inside jails, all over India. “I completed my schooling to my attaining Master's degree while sitting in jail,” he says. In his book, Agnijhara Dingulo, published by Savdachash Prokashon, Chittagong, he writes of his first experience in jail. “The room I was put in was dark and had two light blankets,” he writes. “It was like a jail inside a jail, away from everything. There was one official on guard outside my door all the time. I had arrived at night, after the prisoners were given dinner. Thus, I understood that I would not get anything to eat till the next morning. The guard let me know that there was little water in the corner. He asked me to use it wisely, since I would get very limited water every day which would have to be used for drinking, bathing and cleaning myself. Surprisingly enough, I started to cry. I could not understand why, since I had heard of prisoners going through worse punishments. They would be beaten brutally, lashed to bleed profusely and to make things worse, they would be made to wear iron cuffs around their ankles chained to heavy iron balls. These chains were never taken off, even when they slept or ate. I wonder why the British were ever considered much more civilised than us. I wonder if they treated the prisoners the same way in their own free and civilised country, England.”

Revolutionaries of the yesteryears Mahathma Gandhi (above) and Pritilata Waddedar (below)

While stepping into his 100th year, he had asked for nothing, but for the youth to be bold, undaunted and to shake off fear and cowardice. He asked all to hate injustice and falsehood. “Love your country,” he had said. “And devote yourselves and to the services of your countrymen the country would be changed.” After the Liberation War, Binod Bihari Chowdhury had decided to stay in Chittagong, instead of crossing the border like many of his religious community. His love for his motherland remains as strong as it was since his exciting, danger-ridden days as a resolute revolutionary.

|

| With friend Prabir Chowdhury |

With care giver Bakul |

opyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |