|

Musings

On Geography

Mausumi Mahapatro

|

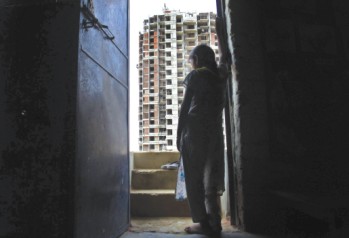

| Photo: Zahedul i khan |

To inhabit a city, to possess her fully, would mean, perhaps, to know her and imagine: her winding curves, the fissures and crevices that lay deceptively indiscernible - a testament to her will to live and endure-, her fertile soils and the fields of her that lay barren, unscathed, and useless. Time, then - the accumulation of living, knowing, exposing, shedding- would determine the degree of possession: a passing traveller would for instance remark on her minarets, towers and facades; a possessor, of her murky faecal chambers wherefrom may lurk defiantly the incandescence of ceaseless strings of oblong pearls. A passing traveller, in remarking on a parched vestibule of desert, would set to memory the camels in Rajasthan, the pyramids in Egypt, and the hanging gardens of yester Babylon. An inhabitant, as Jorge Luis Borghes proclaimed, would not feel the urge to describe these, these symbols of existence interspersed with geography. To the inhabitant, the city would be likened to conquest, meaning, a depth of knowledge, but with emotion, beyond topography and the dull jargon of suppressed acquaintance.

How would the tourist see Dhaka then - as a city of 'dust, three-wheeled locomotives and cycles decorated with the domes of Mecca, and the dizzyingly bright colours worn by those pubescent girls on the street paths as they venture into some time bound space of bondage (in their quest for freedom'?) Would they label her as 'exotic,' a 'wasteland' or 'moderate and 'hospitable'? V.S. Naipaul would claim perchance that it is a city that longs only for the West, as she bows in prayer, in sleep, and in the hours of fortitude, idleness, pleasure and work.

Those tourists to Dhaka, adventuresome enough, seeking to claim her as their own, would venture into the kebab houses in Geneva Colony, their inhabitant friends alongside them, or search for subterranean intellectual life in Aziz Market, take bhelpuris and milk tea near Zero Point and biryani from Hajji's, meet with firebrand revolutionaries in Jagganath Hall and roam in the flood waters of Ashulia. Others of them would perhaps spend their mornings in New Market and Gauchia and their evenings in the aftermath of the call to prayer, or before or during, in the clubs and coffee houses that dot the Gulshan- Banani- Baridhara enclaves, those very enclaves that aspire towards a precise social etiquette, lavish, orderly and sanitised.

Would they grow weary of this city four meters high, frown with a heavy heart at this exile of sorts, though not exactly? Writes Edward Said,

Exiles look at non-exiles with resentment. They belong in their surroundings whereas an exile is always out of place. What is it like to be born in a place, to stay and live there, to know that you are of it, more or less forever?

Can a tourist, or a denizen of a place through chance, though not force of the kind Edward Said writes of, ever grow to love the geography of their fate, or make their own this mixture of blood, nation and probability? Does time, then, as it expands and stretches itself tighten our bond with geography and the nation of proximity or does it make us weary, yearning, in turn, for what we have lost or what we have never known or experienced?

It may well be that a city -her contour, shape and substance- is defined by her lifeblood, who have lived and breathed her stale or fresh vapor, owned her, loved her, pitied her, denounced her, but never left her, though the thoughts of doing so may have entered their minds and habitated there for long. A city, as a fragment of nation, may bind the inhabitant to a formidable beholdingness, out of grasp to the tourist, the immigrant, the forever-branded outsider. It may well be that a city -her contour, shape and substance- is defined by her lifeblood, who have lived and breathed her stale or fresh vapor, owned her, loved her, pitied her, denounced her, but never left her, though the thoughts of doing so may have entered their minds and habitated there for long. A city, as a fragment of nation, may bind the inhabitant to a formidable beholdingness, out of grasp to the tourist, the immigrant, the forever-branded outsider.

But the genesis of cities also tells us that it is the émigrés in their search for the proverbial new life from which a city forms and regenerates, in a cycle of sorts. The memory of a city lasts, presumably, for a single generation; outsiders bring up children who adapt effortlessly and no longer carry the weight of the loneliness of chosen exile. In this way, a city is more porous, more accepting, or perhaps more forgetful than nation.

A migrant from Bogra, Gaibandha or Khulna will never fully accept or be accepted in a city where duration is paramount: whether to have lived a day, a year, a lifetime or a generation determines the intensity of belonging, the tryst, though the possibility exists for these newcomers to one day impose the same question of origin upon others. But what of the person who comes from Patna, Bristol or Indianapolis? Would time matter then or would there always be a bar, a barrier that creeps in into conversation to remind them that they are not the sons and daughters of the soil? The scarlet letter would forever mark them off as foreign to nation, a young nation at that with the unreceding memory of betrayal and war. But it is also not absurd to presume that the foreigner wills to remain as such, to remind the inhabitants who have forgotten that they are indeed foreign, out of pride, identity, and the interchangeability of both. Here nation subsumes geography.

Pride, perhaps, lingers in the narrowest of spaces; to pride ourselves on a common humanity is far more uncommon than to have pride in our god, nation, language, class, region, neighbourhood and so on, though, the violence of communalism and the legacy of our own subcontintent's fractured coexistence reminds us that pride and the loyalties they demand are textured in shifting hierarchies that are not easy to define.

I suppose the same must be true for all nations, though with varying degrees of intensity, determined by their age, maturity, and the relative rapidity of a cycle that turns an outsider into the irrevocable citizen, not the fledgling paper based kind but the one who will remain steadfastly loyal in shunning the enemy common to the nation that binds them together. Or it could just as well be that cycles can reverse, say during periods of war when the emotional outburst of nation ties itself with race and the contiguous boundaries of birthplace, generations before. Memory expands in moments of war, it seems. Remember the Japanese (American) concentration camps in America when Hiroshima burned.

So to live eternally in this way, or with what may more likely be a semblance of eternity as tourist, immigrant, or expatriate – would mean to live with the knowledge of not fully belonging, either at present or in some distant prospective future, and the emotive aspiration towards familiarity that will always remain elusive, yet close enough to seem within reach.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010

|