Cover Story

BANGLADESH'S ART MARKET WAITING FOR A BOOM

SHUDEEPTO Ariquzzaman

M Ali, a young entrepreneur in his 40s, had a craze for collecting posters of Hollywood stars and cars in his teens. His hobby took him to Saju's Art Gallery at Gulshan 2 for the framing service that the shop provided. It was there that Ali got enchanted with the world of painting by Ramiz Ahmed Chowdhury Saju, owner of the gallery and one of the senior-most art collectors of the country. It did not take long for the enchantment to turn into an addiction – as Ali describes how he, while studying in the US, was almost on the verge of spending all his college funds for a painting by Andy Warhol, a famous American artist. Even after twenty years regret rings in Ali's voice as he says, “I should have bought that painting, it is probably worth a fortune now plus to miss out on owning an Andy Warhol...” M Ali, a young entrepreneur in his 40s, had a craze for collecting posters of Hollywood stars and cars in his teens. His hobby took him to Saju's Art Gallery at Gulshan 2 for the framing service that the shop provided. It was there that Ali got enchanted with the world of painting by Ramiz Ahmed Chowdhury Saju, owner of the gallery and one of the senior-most art collectors of the country. It did not take long for the enchantment to turn into an addiction – as Ali describes how he, while studying in the US, was almost on the verge of spending all his college funds for a painting by Andy Warhol, a famous American artist. Even after twenty years regret rings in Ali's voice as he says, “I should have bought that painting, it is probably worth a fortune now plus to miss out on owning an Andy Warhol...”

The traditional perception regarding art especially in the Bangladeshi minds is devoid of monetary attachment. On the contrary, fine arts have been considered as investment in the international arena as early as the seventeenth century. It is the art collector's passion, interest, prestige or ego that provides the value for an artwork and thus creates a market for it. It is not surprising to find people paying millions of dollars for artwork by well-known painters just to keep it in their collection, which in time is likely to bring them a good return. However, very few Bangladeshis would think of investing in art or even have regrets like Ali. Shafiqul Islam, president and CEO of Continental Ltd. is an exception. “In the 80s when everyone was investing in land, I bought paintings with 1.5 to 2 lakh taka,” he says. Those pictures today are worth around 35 lakhs, a change that has taken almost two decades to happen in Bangladesh.

|

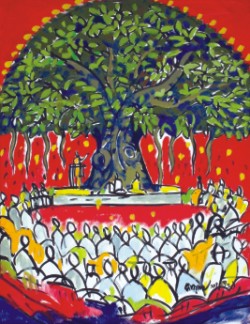

| The love for art often turns into a passion. |

A combination of factors worked simultaneously to bring the market of art in this country where it is today. One of them is the huge increase in the number of buyers, which according to a study by Syed Golom Dastagir, artist and art writer, shows that for the last five years the sales volume of artwork has risen approximately by 30 percent each year. “Even five years ago we used to know the buyers personally, well-to-do people who would often buy paintings, but now the buyer pool has spread so far and beyond that we do not know anyone anymore,” says Luva Nahid Chowdhury, Director General of Bengal Foundation, which is a big player in the art scene. “Back in the sixties it was mainly the foreign tourists who used to buy Bangladeshi art as a souvenir and they basically looked for artwork that represented our daily life,” says Murtaja Baseer, a maestro of art in Bangladesh in the field of purified abstract and metaphysical style. Renowned cultural activist and journalist, Faiz Ahmad, founder and chairman of art gallery Shilpangan, notes that the boom in the garments industry in the mid eighties has led to the birth of an affluent class in Bangladesh that is ready to spend their earning on luxury items.

However, according to Jamal Ahmed, artist and faculty member of the Institution of Fine Arts of Bangladesh, the taste for fine arts took a while to develop among the new elite. It was only when they started going abroad and interacting with foreign buyers that they began to realise the significance of creative art and differentiate it from crafts. Ali tells a similar story of how his taste for paintings developed while working at a senior citizen's home in the US, where weekly exhibitions of paintings were held. Even Shafiqul relates his interest in art to the time he spent visiting the best museums of New York and studying on art history.

The second generation of non-resident Bangladeshis forms another significant buyer group. Unlike their parents who had migrated to foreign countries in search of a living, they have grown up under comparatively stable economic conditions and after the 9/11 incident, they have increasingly become interested in their roots says Luva. “One of the really beautiful ways of connecting to who you are and what you are is art. Most of the galleries get a lot of non-residential Bangladeshi buyers,” she adds.

|

| S M Sultan's paintings are among the most expensive in Bangladesh. |

|

| It is difficult to get hold of artworks of masters like Quamrul Hasan. |

The rise in the real estate industry is another cause that has led to the increased demand for artwork. Jamal Ahmed puts it this way, “There are many nice apartments now, the walls of which cannot be left empty. After setting a sofa worth taka two lakhs from England, they can't put up a calendar in the wall. So they buy a painting and when guests visiting their houses begin to appreciate the painting then their interest grows and they begin to buy more.” As an architect, Luva also points out that the rate of development in infrastructure and housing industry has increased tremendously since 2003 – 2004. “Out of the millions of apartments that are being built even if ten percent people want to keep a painting, then imagine the manifold increase in the demand for art.”

The galleries nonetheless have played an important role in teaching and stimulating the interest towards arts in the buyers' minds. Although Zainul Gallery at the Fine Arts Institution of Dhaka, hosted all sorts of art-related activities till the 70s, it has never been a full-fledged gallery. Even Shilpakala Academy's contribution in developing a market has been minimal. Artists in the 70s and 80s had to rent halls at foreign cultural institutions, or the National Museum to display their works. Among private galleries Desh and La Gallerie were established in the seventies and eighties, however both failed to sustain. Interestingly, La Gallerie during its short span of life even tried arranging an art auction that so far has not happened in Bangladesh. In the eighties, informal art exhibitions arranged by patrons like Shafiqul Islam and Abul Khair Litu were carried out in rented houses in Gulshan. “We used to invite groups of painters and arrange cocktail parties where we would invite our friends and foreigners. The invited guests often felt obligated to buy the paintings. It had a great impact,” comments Shafiqul. Other places where people could go and look for art included Saju's Art Gallery, Tivoli, Jiaraj and few other shops but professional galleries that provided artists with the scope of exhibition came up only in the nineties.

|

Murtaja Baseer |

Shilpangan, one of the first professional galleries that made its way to the current decade appears in Ali's memory as the platform that helped develop a taste among buyers. Faiz Ahmad explains that the motive behind the establishment of Shilpangan was to increase the attraction of the general public towards art and culture on a wider scale. In fact, Shilpangan is one of the first galleries to arrange an exhibition of master prints of European artist in collaboration with France's Daniel Beseche Gallery.

|

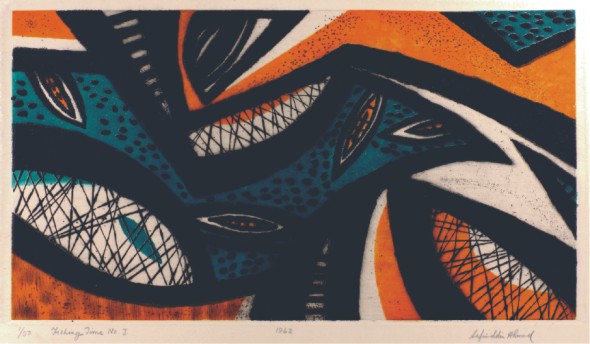

| The work of Safiuddin Ahmed, another master, is one of

the most sought-after. |

|

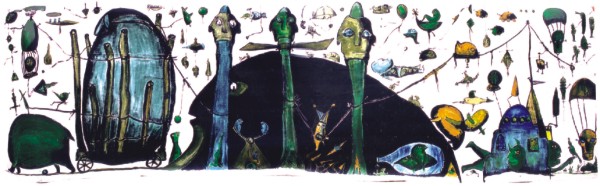

| Shishir Bhattacharjee's “Could have been the Story of a Hero”. |

The beginning of the 21st century brought in a number of professional galleries like Bengal, Chitrak, Kaya that began to solicit artists, arrange exhibitions, print catalogues, and more importantly, set the prices of artworks. An important aspect for an art gallery, according to Luva is the reputation of the person running the gallery. “As a gallery you are telling people that I am going to show you certain kind of art which I feel is good and which is something that you should see,” Luva explains. Thus people need to have trust on the opinion of the art connoisseur who is associated with the gallery. Luva's argument is supported by Ali, the upcoming collector, as he says, “Nowadays galleries like Chitrak, Shilpangan, Kaya are successful because they are run and owned by artists themselves.”

Besides opening up a venue for buyers to shop for a good piece of art, “Galleries firstly provided a platform for the artists and secondly helped set a minimum price for art,” claims Luva. Although Mustafa Zaman, artist and editor of Depart magazine (a quarterly art journal), agrees with Luva's claim of setting a minimum standard price, he feels that artists are still exploited with respect to the financial worth of their work. “ Galleries are keeping between 35 percent to 40 percent, but are not promoting artists to that extent”. He complains that galleries are not doing enough; “A full fledged gallery in the west publishes and writes books on the artist, holds curetted shows based on a theme, they contextualise the work of artist, holds talks and seminars and identifies new trends in the art world. This is not happening here.”

|

Top Left: Kazi Salahuddin Ahmed's “Image of the city-32”. Bottom Left: Anisuzzaman's “Complexity”. |

Despite the difference of opinion regarding the role of the galleries in creating and boosting up the art market in Bangladesh, artists, gallery owners, and art collectors all agree that the price of art has gone up in recent times. Dastagir's study shows that the price of artwork has been increasing roughly by 22 to 25 percent per year for the last five years. “Even two years back my paintings' prices were in the range of eighty thousand to one lakh taka. Now I do not have any picture below two lakhs,” admits Murtaja Baseer. However in Jamal Ahmed's view, the main demand is for the paintings of the top ten to fifteen renowned artists among which Shahabuddin is the most sought after and his paintings' prices have increased 10 to 12 fold. Speaking about his own work Ahmed says that in the last ten years the price has increased from Tk. 20,000 to Tk. 50,000. Ali on the other hand cites a different example. He talks of Shohag Parvez, a young artist, still doing his masters in fine arts; “Four years back I bought his unframed pictures from Charukala at Tk. 450, 850 and 1200 and now he is selling his work for twenty-five to thirty-five thousand to forty thousand taka.”

|

Ronni Ahmed. Lack of appreciation by art specialist and promoters, often

makes the rise of new artists difficult in our country. |

The reason behind the increase in price is not abnormal in Murtaja Baseer's view because the price of essentials including cost of art materials has gone up. Luva justifies the rise in price saying, “Indian art is selling at enormous prices. We believe and I do not think we are wrong that contemporary art in Bangladesh is as good as anywhere in the region. Why then are they selling at stupendous prices and we are not even known. We have to raise our price.” Mustafa explains how Indian art market reached its current position. “Actually without a knowledge base art cannot thrive,” he says holding out a colourful magazine named Art India, “This magazine has played a huge role in making the market for Indian art. It does not publish very intellectually-inclined articles but it is known worldwide and through its discourse it presents which Indian artists are important and why. Once this news reaches the world international galleries call the Indian artist to hold an exhibition. This way Indian market has taken a tremendous leap in the 90s.”

|

Rokeya Sultana. Art collectors often spend a huge sum for paintings by well-known artist. |

Although an optimistic growth is visible in the art market of Bangladesh, Luva thinks that the market is still in its infancy. There is no proper system at work in the country that will assess, evaluate and make known the price of artwork especially if those are not academic or landscape art by an established artist. In fact there is hardly any place for alternative art in Bangladesh, evident in Tayeba Begum Lipi's words “Two dimensional works are widely promoted on the other hand there is hardly any show for sculptures and installations. My husband Mahbubur Rahman and I have been working in installation and video for about fourteen years. Yet we have not received promotion to the extent we deserve.” Only a few of Lipi's works have been sold so far in Bangladesh and she specifies the absence of proper criticism and discussion from art connoisseurs as the main cause. Citing Ronny Ahmed, a contemporary artist who prefers experimentation, Ali opines that lack of appreciation by art specialist and promoters, often makes the rise of new artists difficult in our country. As a result the new generation of artists are afraid to carry out experimentation or start a new trend.

The art market of Bangladesh still has a long way to go, despite the rise of new galleries, increase in buyers and prices and lastly influx of new artists. What the market lacks is a formal shape, which can be developed only when dimensions like institutional buyers, international exposure, art literature and institutional development sets into play. “In our country unfortunately institutional buying is very poor,” says Luva. However, she notes that early on, public institutions like Bangladesh Bank, Janata Bank had acquired art. However now that has stopped which in Luva's opinion may be due to financial constrains or more likely due to a change in the sensibilities of management. Mustafa however remarks that the foreign ministry nowadays, thanks to foreign secretary Mijarul Kayes' personal interest, purchases a bulk of Bangladeshi art every year, which not only helps create a market for art in the country but also promotes it in the international arena through the consulates. Degradation of education in the art institution, political recruitment, lack of initiatives to preserve and collect artworks by cultural institutions and museums are some of the other barriers to the smooth development of the art market, says Mustafa.

So far individual efforts by art lovers, far-sighted and educated businessperson, cultural activists, enthusiast diplomats, maestro artists, expatriates and non-residential Bangladeshis have helped create a market of art in a country where in face of economical vulnerability artists always had to struggle for a living. However, a wide spectrum of activity is actually needed to ensure the continuous growth of the market and young entrepreneurs like Ali sheds a ray a hope there. “I have given many of Ronny's work for display at a exclusive Japanese restaurant in Dhaka, which is frequented by foreigners,” says Ali, as he switches on the lights of his living room revealing the story of his passion for art, the colours and imagination of the artists, the strokes of masters, the experimentation of trend-setters, in all the faces of Bangladeshi art on his walls.

opyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

| |