Cover Story

Boi Para on the Wane

Rifat Munim

Photos: Zahedul I khan

If there is a single word that could describe Bengalis it would be the concept of adda or informal discourse between like-minded people. This is how Budhhadev Bose, the distinguished modern Bengali poet, puts Bengaliness in a nutshell, in one of his literary essays. Bose's insight accounts for the reputation of Beauty Boarding in old Dhaka and Dhaka University's famous Madhur Canteen, two of the most celebrated intellectual hubs in Dhaka, which are considered the focal points of most of the progressive movements of the country both in the pre and post-independence times.

But things began to change when Shahidul Islam Bizu, the proprietor of Pathak Samabesh, spearheaded a campaign of sorts, setting up his bookstore in one of the little shops on the ground floor of Aziz Super Market, a time when most of the shops were yet to be rented out. Soon, most of the publishing houses and bookstore owners from New Market and Bangla Bazaar followed in the footsteps of Bizu starting up their businesses in the market. Like blossoms attracting honeybees, the bookstores, in the span of less than a decade, drew in most of the budding as well as established writers. The virtually god-forsaken place soon turned into the new intellectual hub, where the old and the young converged in search of a new mode of expression, brushing aside all that seemed intellectually stale.

Ever since the market gained momentum, it began to represent the intellectual and creative height of the country with publications such as the oeuvre of Araz Ali Matubbar, and writings of Ahmad Sharif, Humayun Azad, Ahmad Safa and many more. It also became the meeting place for all the up and coming writers along with numerous little magazine activists who spent hours talking and debating over the political and literary issues while leafing through the new titles from one shop to another. Not only writers, but also numerous theatre activists, filmmakers and musicians rushed to the place mostly in the evening to exchange ideas. In other words, the whole place became the intellectual genesis of all the radical thoughts and ideas of arts and politics, be it modern or post-modern.

|

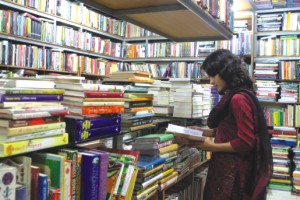

| A reader leafs through books in a bookstore at Aziz Market. |

The present depicts quite a different scene. With the onslaught of local boutiques and other commercial enterprises, the prospect of an expanding book market coupled with a congenial atmosphere for creative adda is on the wane. The onetime intellectual hub has now metamorphosed into a noisy haven for shop-a-holics with new boutique shops getting the upper hand on every floor, clearly indicating an intellectual vacuum that is yet to be filled.

Talking about those golden days, most of those writers become nostalgic and contemplate sadly at the prospect of whether those times can ever be retrieved. Even though many foresee a further dwindling of the bookstalls as more capital finds its way into the hands of the boutique house owners, they stress the need for preserving the sanctity of such a place that plays a pivotal role in safeguarding the nation's intellectual direction.

When the nascent market was spreading its wings with newer shops like Sandesh, Boipotro and Srabon kicking off, a group of young writers belonging to the 1980s first established their foothold in the market toward the end of the decade. The group, which includes Masud Khan, Selim Morshed, Sajjad Sharif, Shantanu Chowdhury, Subrata Augustin Gomez and Parvez Hossain, would gather either at the Bishya Sahitya Kendra or the Pappu restaurant adjacent to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University hospital and were on the lookout for a new place, which would provide them with a much broader platform to break free from the shackles of hackneyed thinking.

“Aziz Market was in its infancy when we started off gathering there. Back then we were already writing for the little magazine Sangbed. As most of us were alight with new ideas and beliefs, we embarked upon setting up Gandeeb, our own little magazine, discovering ourselves in the midst of a whole lot of people encompassing not only our friends, but also the younger writers,” says Sajjad Sharif about the beginning of the Aziz Market era.

|

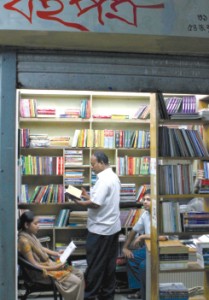

| Readers are beginning to throng the newly formed Concord book market. |

Soon filmmakers Tareq Masud and Tareq Shahriar, painters Dhali Al Mamun and Shishir Bhatyacharya, and many theatre activists joined hands with their writer friends in a bid to make Aziz the nucleus of all creative activities. Bangladesh Short Film Forum and Documentary Film Society opened their offices while some radical leftist political parties including Revolutionary Students' Unity and Ganasanghati Andolan set up their branches there, holding regular study circles on the various facets of Marxism. This new wave of alternative thinking was to be followed by many progressive organisations including Unmesh Sahitya Sangsad (initiated by Mohsin Shastrapani), Bigyan Chetona Parishad, Bhasani Parishad and Jatiya Kabita Parishad, which added a new dimension to the scientifically oriented thoughts invigorated by the write-ups of Araz Ali Matubbar.

“Think of the extent to which all forms of creative and progressive people flocked together at Aziz Market,” reminisces Parvez Hossain, the editor of the little magazine Sangbed.

“Once we started chatting about a philosophical or literary topic, we went on for hours,” he says, “Anytime some people would join while some others would leave, but the discussion would continue undeterred exerting a certain impact on those who took part. What distinguished these addas was the liberal atmosphere which was open for both our juniors and seniors.”

“It was my ceaseless adda at the Aziz Market that taught me how one can also learn from the younger ones. I was an ardent follower of 'art for art's sake' that sought to uphold aestheticism in literature,” reflects Sharif. “But when I met the younger breed of writers, some of whom were influenced by neo-Marxist thinkers like Louis Althusser, my literary perceptions took to a totally new turn. Sometimes I really miss those days!”

Soon the writers of the 1980s became preoccupied with their careers and it was time for the writers of the 1990s to take the lead. Once they got into their stride, they invigorated the activities luring more and more people from all branches of the arts. On the one hand, there were writers like Ahmed Mustafa Kamal, Bratya Raisu, Alfred Khokon, Tokon Thakur and Marjuk Russel, among many others; on the other hand, there were the filmmakers Mustafa Sarwar Farooki, Jahidur Rahim Anjan and singers Bappa Majumdar and Sanjib Chowdhury.

|

|

| Members of Bangladesh Short Film Forum at its office. |

Poet Nurul Haq at the Antara restaurant on the first floor. |

Although this generation began its journey by occupying the sidewalks adjacent to Samabesh and Sandesh, they later shifted to the stalls of Srabon Prakashani and Little Mag Prantor.

“What began merely as a meeting place of some like-minded young writers soon turned into the breeding ground of a myriad of powerful poems, short stories, literary criticisms, songs, dramas and what not. Although these addas were very informal in nature, things that we discussed were soon to come out in publications most of which were appreciated even by the intellectuals,” says Ahmed Mustafa Kamal, an award-winning prose and fiction writer of the 1990s.

Added to this was the highly intriguing presence of renowned writers such as Nirmalendu Goon, Mohammad Rafique, Humayun Azad, Abdul Mannan Syed, Mahadev Saha and Rafiq Azad, among many others, who used to hang around the market not only to collect the latest books from home and abroad, but also to gossip with the younger generations.

|

|

| Manzare Hassin Murad chats with filmmakers at the office of Pramannokar.. |

Members of Bigyan Chetona Parishad at its office. |

“Although sometimes I met Goon and others from our generation, I usually spent time with the young writers and took great pleasure in listening to their thoughts and vice versa,” says Mohammad Rafique, an eminent poet of the country, who won the Ekushey Padak 2010 in literature.

Some of them especially Samudra Gupto and Ahmad Safa deserve special mention for their continuous communication with the younger generation. Gupto was involved with Unmesh and used to sit in the stall named Muktochinta while Safa rented a shop to publish the magazine Uththan Parba and exchange ideas with new writers.

“But that the same place is now occupied by the boutique houses is a matter of great regret. I no longer feel like going there because people who now throng the market are very different from our time. If this situation goes on, there will be no bookstore in the near future,” opines Kamal, an argument echoed by Parvez Hossain.

Many writers of the 1990s believe that this is the natural consequence of a free market economy, which is epitomised by the victory of bigger capital over the smaller one.

A black banner of condolence mourning the death of Abdul Mannan Syed hangs over the stall of Pathak Samabesh.

“If you want to make money, you must invest in fashion wear, not on books. That's how fashion has dominated intellectual stimulation, dampening the liberal atmosphere for literary addas eventually,” says Prashanta Mridha, a fiction writer of the 1990s, who in his non-fiction Sanyaser Sahachar, published recently by Shuddhashar, offers a highly entertaining account of many of his addas with the above mentioned writers and shows how growing consumerism has taken over the boi para in the recent years.

Bookstore owners, however, think that there has not been any real drop in the number of bookstalls.

“I don't think there has been any significant change. Only the previously closed shops were rented out to the boutique houses. May be one or two bookstalls have vanished,” opines Bizu.

Many, on the other hand, challenge such an idea. Talking to many bookstall owners of Aziz, it has been found out that the market, which once saw the existence of a total of more than 40 bookstalls, has now shrunk to about 20.

Most of the rows are now taken over by the mushrooming

boutique houses.

“ The number of bookstalls has decreased at least by 50 per cent,” says one of the stall owners on condition of anonymity. Along with Srabon, which made a name for itself by arranging poetry recital programmes by the poets themselves, many popular stalls including Muktochinta, Boipotro, Soumya Prakashani, Kaljayee and Adhuna have vanished in the past few years.

“Following the success of many fashion houses, the Aziz Market Owners' Association suddenly increased the rent which is affordable for the lucrative businesses of boutique shops, but not for us,” observes Shihab Bahadur, the proprietor of Muktochinta.

Despite the glamour of the encroaching boutique shops, a handful of bookstalls mostly located on the ground floor of Aziz still attract bookworms with their rich collection of creative and critical books from home and abroad. Some of these shops include Samabesh, Papyrus, Prathama, Janantik, Paruaa and Bidita. Despite all obstacles, regular literary addas, although in a much lesser degree, are still held centring around the bookstalls Banglar Mukh and the Little Mag Prantor.

|

A stall at Concord tower. |

Offices of the progressive political parties and many of the cultural organisations are now all gone. Even the existing ones are likely to face extinction soon given the increased rent of each shop. Yet some creative adda still take place at the existing cultural organisations including the short film and documentary film forums, and Bigyan Chetona Parishad.

Yet according to filmmaker Manzare Hassin Murad, nothing changes the fact that the vast range and vibrancy of the literary and creative gatherings have dropped significantly as a result of the invasion of clothing boutiques.

“Although many writers and cultural activists still throng the market, it has indeed lost its former lustre,” reflects Murad.

In the wake of such realities, a number of the vanished bookstores including Boipotro, Muktochinta, Srabon and Sanghati have found their way to the ground floor and basement of the Concord Tower at Katabon, an awkward location indeed for an emerging book market since most of the bookstores are situated at the basement where daylight is seldom allowed. Arun Ganguly, the owner of Boipotro, was the first to initiate his stall at Concord in April 2009.

“Depressed by several factors like the increased rent (at Aziz Market), I decided to shift here. At first, I was a bit unsure about the prospect especially because it doesn't attract booklovers, as you can't tell that there are bookstores in this building. But as almost one and a half years went by, I think a lot of people including the writers are becoming oriented toward it,' says Ganguly.

Lower rent and a dearth of other commercial enterprises, observes Bahadur, have encouraged many to found their newly established publishing houses and bookstores at the basement of Concord. Stalls like Madhyama, Agradut, Jayati and Balaka, among others, are having regular visitors with satisfactory sales, says Moni Mohammad of Agradut.

|

| Books on display at Aziz. |

Seeing the success of Concord, some bookstore owners of Aziz have also opened their branches here, Takkhasheela and Parua being two of such stores.

Now the Market has about thirty small-sized bookstalls. Following the recent two-week-long book fair to mark the rains, the alternative market has got some publicity. Moreover, the regular weekly boi-er haat(book fair) organised in the fashion of chhobi-r haat (art fair), has gone a long way to attract readers especially from Dhaka University. In line with a growing readership, the market also seems to build a platform for regular creative adda.

Tokon Thakur, one of the distinguished poets of the 1990s, frequents Concord market regularly and finds it quite interesting to hold an adda there.

“It has been quite some time since I hung out in this place in the evening. And I think it's going to be the future hub for literary and intellectual gatherings,' says Thakur.

Despite a fresh beginning, this market is far from bouncing into the vibrant alternative many are hoping for. It cannot match the range of books offered by the stalls of Aziz. But the necessity of a quintessential book market can hardly be overshadowed. On one hand there is the declining Aziz Market, on the other hand there is the yet-to-be-flourishing Concord market, demonstrating an obvious vacuum in creative as well as intellectual pursuits. Finally what is at stake is the previously held vastness of the space at Aziz, which was once filled in with the overflowing enthusiasm of youth and the wisdom of older generations.

While many believe that the predominance of Internet and media especially TV and film have marginalised the bookstores along with people's reading habit, many are of the opinion that a strong campaign on the part of the government and the intellectuals is indispensable for bridging the gap between a market and a platform for literary gatherings.

“Litterateurs cannot live without adda. History testifies to the fact how literary addas gave birth to many classic pieces of literature. So we must retrieve those golden days or create a new place for affable literary addas, which is not possible without proper patronisation. I think the government should come up with a strong campaign to work to that end,' says Rezauddin Stalin, a poet and writer of the 1980s.

opyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |