|

Art

Grotesque with Panache

Fayza Haq

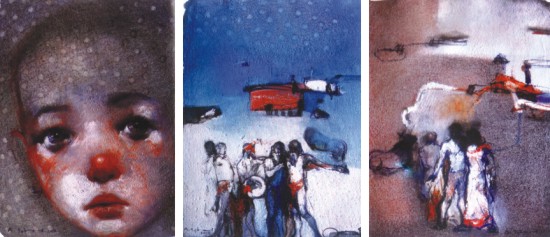

L-R: Innocence-3, oil on paper, 2010, Unfettered Life-2, oil on paper, 2010, Conversation-1, oil on paper, 2010.

Photos: courtesy

Mohammad Iqbal, with his PhD from Japan, is not just an oil painter with bagful of pompous degree. He has solos before in the city but his current exhibition at “Chitrak” is not “déjà vu”. The translucent dots and etched – in sharp, dramatic lines that hold his figures and forms together are something stirring and unforgettable. The paintings are soothing, despite having bitter and angry thoughts about ruination in the environment. Iqbal deals with life worldwide and not just Bangladesh.

His figures are global, as one studies the details of the eyes and lips. Yes, he has stressed on details such as cattle, the dhol, dhotis, lungis and saris of the Bengal. With simple, striking colours he has filled his figures with passionate feelings. Combining nostalgia with the present, Iqbal has thrust home his message of the apprehension for the future. Subtlety is the backdrop of his stylish statements. Though angst-ridden, his is poised–and certainly not carried away with his feelings and fears.

What Iqbal has stressed on is the present society, in which the child is not given the necessary care and warmth, which is essential for a child's upbringing. He points out that this was there in his childhood, and is still prevalent in most villages. He does not consider only child labour in the cities in homes, but also commercial places – such as the shops, factories, streets and docks. Where there should be games and education, there is sweat and grime. More importantly unhealthy exposure as in the cement factories.

|

| Unfettered-1, oil on canvas, 2010. |

“There is a mad rush of our commercialised existence, when people and their children are being trained to get ahead like robots,” says Iqbal. The villages are being destroyed and the trees felled to make room for multi-storied buildings – containing factories and buildings for banks, insurance places and other corporate outlets. Offices and malls crowd residential places like Dhanmandi. Parks and playgrounds are being bought up with “black” money. This is the lament of the artist, with his delicate, but flamboyant brush sweeps and strokes.

He says, “It is global anti-humanism, that is thrust upon the children, in general, that I cry out against. This is specially so during man-made and natural calamities. When I was four years old, the Liberation War took place in Bangladesh. I still remember the fearful experiences of that time. I felt the contrast very sharply – when I paused and dwelt deep on the Buddhist philosophy and the wonderful education system, in Japan, where I enjoyed my final stage of education.”

“Being curious of world news through the mass media, I realised that problems faced by children were not limited to the so-called 'third world'. Even though poverty does not cripple the home and hearth of those in the US and Europe, as in case of both the parents rushing to work in the west, the child is not given the attention, which he needs. There are cases of abortion – even in the progressive metropolises, such as New York and Paris, as is well known. I don't want to criticise any country. However ours is free from this evil. This is the effect of the mechanical routine of modern existence, which stresses on a 'single child family'. Even when the family is 'free from want', there is no true joy, warmth or love in it.”

|

| Cow Boys, oil on canvas, 2010. Photo: Courtesy |

Like many 21st century passionate artists, Iqbal is preoccupied with environmental issues. He is concerned about the future generation. His portraits of children reflect the emptiness of their life, he says. They are symbols or loneliness and despair. Today, he says, life is so simplified with machines etc. we get what we wish and are blasé with it. “There is no joy of tilling the land, growing our own crops, catching one’s own fish or hunting down our honey bees. The readymade, mass-produced items are produced at the cost of our trees and rivers. Ugly smoke emanate from the city chimneys – especially in the cities; and so create slums, diseases, and leave us fretting after more materialised goals. 'Civilization and destruction' was the title of my PhD thesis. Bangladesh is not so much to be blamed for the greenhouse monstrous effect as the so-called First World industrial countries. I just want to cry 'Hoa!' to this nasty, menacing phenomenon modernisation i.e. – as do all true, creative thinkers and artists.”

Iqbal does work from photographs or layouts. His figures are products of his imagination, feelings and emotion. As one witnessed Iqbal at work in “Chitrak” this time, and having admired his work in other venues, such as “The Bengal Gallery” one is impressed.

Iqbal's education in Japan was undoubtedly a useful one. There, his environment, with its soothing cherry blossoms, snow-capped mountains, rhythmic waterfalls, gliding and twittering birds and the high-crested ocean waves certainly inspired him. It provided the tranquillising setting for his gathering of expertise in oil colours.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

| |