Cover Story

TRADING IN TRANSPORT

The widening trade deficit between Bangladesh and India has been a sore point for Bangladeshis. Compounded with this are a number of unresolved issues ranging from the Tipaimukh project and demarcation of maritime boundary to the long-standing border tensions. Against this backdrop, a bilateral agreement on the transit issue between the two countries is on the cards. As always, political leaders are at loggerheads over the pros and cons of transit. Despite all the critical speculations, experts believe that if transit is dealt with properly, it will substantially add to national income.

Rifat Munim

The joint communiqué signed by the premiers of Bangladesh and India in January this year lays emphasis, among many other issues, on the much debated issue of transit. The highly political issue was brought to the fore again when the Bangladesh Customs in early October seized two Indian ships that had refused to pay the transit fee as stipulated by a fee structure imposed by the National Board of Revenue (NBR) in line with the agreements reached in the communiqué. As the customs authorities charged the newly enforced transit fees, the Indian side asked for a waiver on the basis of the Protocol on Inland Water Transit and Trade (IWTT) signed by the two countries in 1972, which does not mention any transit fee but has the provision of paying Bangladesh an annual charge of five crore taka for maintenance of the river routes. Following a meeting between the Finance Minister AMA Muhit and the Indian High Commissioner Rajeet Mitter the fee stipulated for transit through the waterways was withdrawn, and the IWTT protocol resumed. The joint communiqué signed by the premiers of Bangladesh and India in January this year lays emphasis, among many other issues, on the much debated issue of transit. The highly political issue was brought to the fore again when the Bangladesh Customs in early October seized two Indian ships that had refused to pay the transit fee as stipulated by a fee structure imposed by the National Board of Revenue (NBR) in line with the agreements reached in the communiqué. As the customs authorities charged the newly enforced transit fees, the Indian side asked for a waiver on the basis of the Protocol on Inland Water Transit and Trade (IWTT) signed by the two countries in 1972, which does not mention any transit fee but has the provision of paying Bangladesh an annual charge of five crore taka for maintenance of the river routes. Following a meeting between the Finance Minister AMA Muhit and the Indian High Commissioner Rajeet Mitter the fee stipulated for transit through the waterways was withdrawn, and the IWTT protocol resumed.

Although charges for the road and rail routes in the fee structure still remain in force, withdrawal of the river transit fee has raised questions about the possibility of an effective set of rules for transit fee. Against such allegations the finance minister asserted that there would be no free transit and formulation of a totally new set of rules, which is supposed to be completed by December 2010, would replace all the existing charges and fees. A senior official from the NBR also echoed the finance minister saying that a committee involving several ministries including foreign affairs, finance, commerce, communications and shipping was working to that end. The commerce ministry will head the committee, he added. Nevertheless speculation about national security and the widening trade gap existing between the two countries has not lessened. According to a report by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics published in 2009, Bangladesh's trade deficit with India in the fiscal year 2007-2008 was $2.8 billion. Many believe that the gap will further widen if transit is given.

|

A huge sum of diverted goods through the road routes of Bangladesh may generate a lot of money for the country |

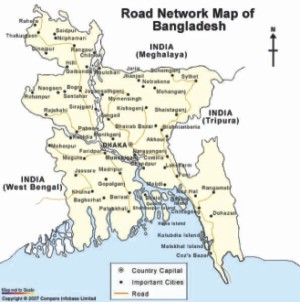

Transport experts and economists, however, are sanguine about the prospect of transit. They believe that Bangladesh is blessed with a unique geographical location with two landlocked countries (Nepal and Bhutan) and a nearly landlocked region of northeastern India at its hinterland. So development of regional connectivity in South Asia largely depends on the transit traffic through Bangladesh. Negating all the pessimistic speculation about the drawbacks of transit, Dr Rahamatullah, the former director of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, opines that the advantageous geographical location of Bangladesh can turn the service of transit traffic into a viable industry that can generate national income and create employment opportunities at the same time.

“Establishment of regional connectivity will provide tremendous opportunities for these regions as well as for Bangladesh to trade in transport services and develop itself as a 'transport hub'” he says.

Rahamatullah differentiates 'trade in transport' from 'trade in commodity' in that the former earns by providing transport services while the latter involves earnings from exports and imports.

“Not all the countries have the opportunity of trading in transport. Besides, the importance of an efficient integrated transport system between regions cannot be overemphasised in today's competitive world economy. So we should utilise the trade opportunities offered by our unique geographical location,” he affirms.

Lack of adequate as well as in-depth study has given rise to various misconceptions about the multifaceted issue of transit and transhipment. Many have likened it to the concept of ‘corridor’, misconstruing the whole thing, and hence have opposed it in the most vociferous manner. Lack of adequate as well as in-depth study has given rise to various misconceptions about the multifaceted issue of transit and transhipment. Many have likened it to the concept of ‘corridor’, misconstruing the whole thing, and hence have opposed it in the most vociferous manner.

When a 'corridor' is given, a country gives certain privileges or control on the land to the receiving country while in transit there is no question of such rights in the territory allowed for transit. Transit provides only transport facilities under certain conditions, which can well be withdrawn if necessary. For example, under the Bangladesh-India 1974 Land Boundary Agreement which was partly addressed in the joint communiqué, Bangladesh wanted a lease in perpetuity an area of India's territory (178 metres x 85 metres) near Tin Bigha to connect the Dahagram enclave with main land of Bangladesh. Eventually, Bangladesh did not get the corridor.

'Transhipment' refers to the same inter-country passage but mandates Bangladeshi-owned transportation whereas in transit Indian-owned surface transport will move through the transit territory from one end to the other. In the present case, India wants to dispatch goods and other materials from the western parts of India to its northeastern states through Bangladesh where the question of India's rights on the land territory of Bangladesh is completely irrelevant.

Yet political leaders are divided in their opinions about the pros and cons of transit. BNP Vice-chairman Shamsher Mobin Chowdhury is highly critical of allowing transit to India until the unresolved political issues are properly addressed.

Rail routes also need reconstruction and can bring us a huge amount of transit fee.

“At first we were told that the transit would bring us a lot of money but now we hear that there will be just transit fee, but no duty to be imposed on the diverted goods. This is how such a serious issue is being dealt with while keeping the people of the country totally in the dark,” he says.

Duty is usually imposed when a product is imported from a foreign country, a fact that is also true of other countries. In matters of transit, only fees can be charged, says a customs official on conditions of anonymity. When Chowdhury's attention was drawn to this fact, he says, “ Other countries do not have a neighbouring country which always tries to dominate in terms of river water sharing, border killing and sealing off the border. We should never alienate transit from other outstanding problems especially those which are taking a heavy toll on us.”

“At first we should resolve those problems, then we should think of the transit. We also believe in peaceful relations with our neighbours, but not at the cost of our own interest,” he adds.

Senior Awami League MP Tofail Ahmed, on the other hand, says that it was late president Ziaur Rahman who initiated the process of transit through a bilateral agreement with India in 1980. “The BNP government extended that agreement in 2006, so we are just continuing that legacy,” he adds.

About the inter-relation of transit with the unresolved political issues, Tofail says, “Transit is a separate economic issue which has hardly anything to do with water sharing and other such issues.”

Prior to the partition of India in 1947, the trade between the northeastern sub-region of South Asia and the rest of India passed through the territories of what is now Bangladesh. Rail and river transit across the erstwhile East Pakistan continued till 1965. After Bangladesh's independence, only the inland water transport was restored in 1972 based on the IWTT Protocol. Due to various political changes in the post-colonial periods an integrated transport system between the regions of South Asia now remains fragmented. As a result, Europe-bound consignments of Assam Tea now travel 1,400 km through India's 'chicken neck' to reach Kolkata Port. Moreover, traffic from Tripura now travels 1,650 km to reach Kolkata port, a distance that could be covered by travelling only 400 km if transit through Bangladesh was possible.

By allowing transit to India, Bangladesh will not only earn from freight and port charges, but also from the transit fees imposed on the foreign goods to be carried through its routes. In addition, experts believe that the transit fee should include 70 percent of the transport cost that India would save by diverting its goods.

Along with transit fee and charges, the issue of reciprocal transit has been raised by many quarters. Professor Mustafizur Rahman, an economist and executive director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue says that since Bangladesh does not at the moment require any transit through India to facilitate its export, it sought Nepal and Bhutan's transit through India so that they can use the Chittagong and Mongla ports and other road and rail routes in order to export their goods to Europe or other Asian countries. He also informs that at present Nepal has to use the Kolkata port because of India's restriction, which highly escalates its export cost.

As mentioned in the joint communiqué, India for the first time has agreed to allow transit to Nepal so that the latter can use the rail and water routes of Bangladesh, adding substantially to Bangladesh's overall transit profit. Bhutan's transit is still under consideration.

Apart from many other issues such as demarcation of maritime boundary, the Tipaimukh project, balancing the trade deficit and tariff and non-tariff barriers imposed by India on Bangladeshi import products, the “Joint Communique” specifically mentions the following:

-Bangladesh will allow use of Mongla and Chittagong seaports for movement of goods to and from India through road and rail.

-Ashuganj in Bangladesh and Silghat in India shall be declared ports of call. The IWTT Protocol shall be amended through exchange of letters. A joint team will assess the improvement of infrastructure and the cost of one-time or longer-term transportation of ODCs (Over Dimensional Cargo) from Ashuganj. India will make necessary investment.

-Construction of Akhaura-Agartala rail link, which will be financed by grant from India.

-India agreed that Rohanpur-Singabad broad gauge railway link would be available for transit to Nepal so that the latter can use the Mongla and Chittagong seaports. Bangladesh requested for railway transit link to Bhutan as well.

According to a revised study being conducted by the South Asian Centre for Policy Study (SACEPS), the road routes from Karimganj, Sutargandhi to Sylhet, Dhaka; the rail routes from Karimganj to Kulaura and from Mahishasan to Akhaura, among others, will also be used to implement the project.

However, implementation of all these agreed-upon and proposed provisions has to be preceded by the Herculean task of infrastructure development that, according to the study, will require about $ 5 billion in the next five to seven years given that the cost will further increase in the years after that. The Asian Development Bank and the World Bank have already consented to provide the soft loan on condition that Bangladesh will reform its rail and road routes, and seaports. India has also agreed to make some investment. In addition, if we can develop the deep-sea port at Sonadia in Chittagong, further possibilities of connectivity with India, Nepal, Bhutan and China will open up.

Dr Rahamatullah, who is the team leader of the joint study for the SACEPS, elaborates on the hectic infrastructure development and points out the conditions of the road and rail routes which are not fit for overloaded vehicles.

“To materialise the transit project, many roads and rail links need to be constructed while many need to be renovated. The Dhaka-Chittagong highway is narrow. Some part of it is dilapidated as well. As for the rail routes, our railway tracks are weak and our rolling stock is old. Besides, the Dhaka-Chittagong rail route is completely saturated.”

“An entirely new bridge along the Jamuna Bridge needs to be built for facilitating railway-transit, which alone would cost nearly $1 billion. The seaports and the river port of Ashuganj in Brahmanbaria also need massive renovation and reconstruction,” he says.

Considering the amount of cargoes that may be diverted through Bangladesh, one can assume the earnings that Bangladesh can garner from the facilities. According to the revised study, a total of 18 million tons of cargoes will be diverted through the routes of Bangladesh. This projected amount also encompasses the Nepalese cargoes that now use the Kolkata port. Although Rahamatullah declined commenting on the profit rate, he implied that the massive investment on the part of Bangladesh would be worth its while.

“We are yet to complete the study. Still in view of the cost-benefit analysis and the risk analysis, it can be said that the profit coming from the transit traffic will add substantially to the national economy,” he says.

About national security, Rahmatullah says that if transit was threatening to national security, then the river transit existing from 1972 would surely jeopardise our national security.

Freight charges can also be good source of earning.

“All the goods, be they carried by transit or transhipment, must be strictly scanned by our customs. So there is not much chance that illegal or smuggled goods will be transported,” he adds.

Rahamatullah also informs that only about 10 percent of the full potential benefits can be realised during the first five years when the various projects to develop infrastructure will be implemented. From the sixth year onward, it will be possible for us to realise full potential benefits.

So the question is not so much of security as of a viable fee structure for the diverted Indian goods and reciprocity of transit, and inter-relation of the unresolved political issues with transit- all of which together will ensure our national benefit. Only such a deal will enable us to minimise the trade deficit to some extent.

“Firstly, we must ensure the freight and port charges. Then fixing a transit fee is of utmost importance, which should include maintenance cost, toll and more than half of what India saves. Since our vehicles will also use the infrastructure, charge for the maintenance cost should be fixed in a win-win manner,” says Mustafizur Rahman.

Rahman also thinks that transit is in no way a one-dimensional issue and stresses that the Bangladesh side should relate transit with other unresolved issues while negotiating fees and other related charges.

Finally the time-consuming process essentially calls for political stability in a country where the politics of violence and acrimony is taking its roots more persistently than any time before. Such a political backdrop can at its best falter the progress of an effective project initiated during the tenure of the former government. Hence political stability for the sake of greater national interest is a must not only for the successful implementation of transit, but also for all the unresolved issues with other countries, be it India or Pakistan.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |