Cover Story

Behind the Scenes The Stock Market Saga

On January 9, 2011 the benchmark index of the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) suffered the steepest ever single-day fall in the bourse's 55-year history. The DSE General Index (DGEN) plunged by 600 points, and all indices fell nearly 8 percent in the wake of panic-sales. Breaking the previous day's record, on January 10, DGEN shed 660 points or 9.25 percent between 11 am and 11:50 am. The capital market was shut; small investors turned vandalistic; and the business district of Motijheel was transformed into a battlefield between protesters and law-enforcers. Despite the measures taken by the regulatory commissions, people suffered major financial loss and worse than that, many lost confidence in the stock market. After the big boom in 2010, what caused the disasters witnessed during the past one and a half months? How secure is the securities market?

..................................................................................................................................................

AANTAKI RAISA

The recent market collapse was not a one-day event. Bangladesh stock index marked 80 percent growth in the year of 2010. The bull run, however, faced its first halt in December 2010. On December 8 DGEN suffered the third highest single-day plunge since 2001 losing 185.53 points or 2.12 percent. Eleven days later on December 19, DSE suffered its biggest crash, of course up until then, as the index nosedived by 551 points or 6.72 percent at the close of a four-hour trading session. The raging bull was finally tamed on back-to-back record plunges on January 9 and 10. The upheaval continued as the DGEN, after the nosedives, took a high jump rising more than 15 percent which was the highest one-day spike ever –a rebounding record. To understand what actually triggered the Sturm und Drang in the stock market one has to go back to the story behind the rise of the stocks and then come to understanding the falls.

Pre-December 8: The Expansion Epoch

2010 was considered a boon year for investors, although a record fall in December created massive panic among those who had put their money in stocks. There was hardly any investor who made losses in 2010. The stock market witnessed a manifold boom –the price index, turnover, market capitalisation and its ratio to GDP (gross domestic product), and the number of new arrivals both in terms of issues and investors. The Dhaka market ranked third globally in terms of performance, according to an analysis of LankaBangla Securities.

Analysing the reasons behind the upsurge, the former CEO of the DSE Professor Salahuddin Ahmed Khan, also a teacher at the Department of Finance of Dhaka University says that the reasons are quite simple and logical. The country had been in a stagnating position in terms of investment for the last few years. Initially the military junta caused a halt in investment, followed by a lack of power and gas supply that forced the government to stop new connections to any end users.

|

The investors turn vandalistic as the DSE index declines

at a record rate. PHOTO: STAR FILE |

Consequently, in a country having more than 32 percent national savings and poor state of investment, a lower rate of nominal interest rate, negative real rate of interest rate encouraged many new investors to the market. Such new entry was also supported by easier access to the market due to branch expansion by the brokers. Meanwhile, financial institutions also found that, due to lack of business opportunities they were being burdened with huge amounts of excess liquidity. The cost of bearing the extra liquidity could not be utilised in alternative investment avenues where the securities market ushered the path for fund deployment. During this time, as the real investment scenario was unclear, so flows of new securities in the form of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) were also quite scanty. To add to the misery of the market, the government imposed some unnecessary restrictions on the IPOs causing the flow to slow down further. The restrictions were partially lifted by November.

Another problem was caused by poor monitoring and market surveillance which resulted in abnormal price behaviour for many securities, especially for those securities where free float shares are few or the company is very small and so an imperfect market situation enabled the prices to rise significantly. All these factors caused the prices of most of the listed stocks at DSE/CSE to reach an abnormally high level.

An inside trader in the DSE, preferring anonymity, informs that during the recession of 2009-2010, the banks in Bangladesh had a lot of idle money in reserve. “Bluntly speaking, when the banks had huge monetary reserves, acquaintances of the bank officials and other people as well, took bank loans to invest them in the share market. This brought an overflow of liquidity in the market. I saw the price of a share increase by Tk 40 in one day whereas it wouldn't have increased by Tk 3-4 in a normal market,” he says.

Due to the opportunity of making huge profits, 1.5 million new investors were investing in the stock market in 2010. According to Centre for Policy Dialogue's (CPD) analysis, the total number of beneficiary owners' (BO) account holders was 3.21 million on December 20 last year, which was 1.25 million in the same month a year before. This number increased by 154 percent in 2010. The opening of brokerage houses at the district level (238 brokerage houses of DSE opened 590 branches at 32 districts), arranging a countrywide 'share mela (fair)' and introducing interest-based trading operation, easy access to market information, were some of the factors identified by the CPD that accelerated the flow of investors.

December 8, 2010- January 11, 2011: The Big Crunch

|

The number of BO account holders increased to 3.25 million by

December 2010 as the stock market booms. Photo: zahedul i khan |

The booming bubble finally burst, the bull run finally stopped; on December 8 of 2010 with the third highest plummet since 2001, the DGEN closed at 8585.88 with a loss of 185.53 points. That was just the beginning; on December 19, the DSE witnessed the steepest till date single-day fall – 551 points or 6.72 percent to 7654.41, beating the previous record fall of 3.32 per cent or 284.78 points, set just one week back on December 12. The down slope of the index continued till January 10, 2011, with frequent record sets and breaks. According to Professor Salahuddin Ahmed Khan, since in a market environment, prices cannot remain very high for a prolonged period, the downward slide was quite predictable. The rate of decline was basically due to the nervous state of the market participants. Well, no divine order triggered the continuous plunges in the stock market. A series of events, actually, made it quite inevitable.

On December 1, the Central Bank sent 50 teams on surprise visits to different bank branches in Dhaka and Chittagong after it received complaints that the banks were investing in the stock market from their reserves to make profit. Some banks were in fact found involved in such irregularities. During that time, the daily transaction in the share market was on an average of Tk 2000 crore and sometimes even Tk 3000 crore, which was double compared to that of the previous year (2009).

The DSE Index grew almost 2500 point without any major price correction by December 2010. To bring the ever increasing price of shares in the market under control, both Bangladesh Bank (BB) and Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) had sent different directives; Bangladesh Bank initiated the withdrawal of illegally invested industrial loans from the market by December 31, 2010 and raised the Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR) and statutory liquidity requirement (SLR) both to 6 percent and 19 percent respectively to safeguard the interest of the depositors. According to Sharif Mohammad Kibria, an employee at a renowned merchant bank this might be one of the reasons to blame for the recent fall of the market as it took away at least 2000 crore hard cash from the money market resulting in less capacity of investment. According to Abu Nayeem Md Anuruzzaman, another employee at the same bank, though former SEC member Monsur Alam's two directives– netting or adjustment facilities (Sell before buy), and en-cashing of cheques submitted by investors against their share purchase orders– were blamed to influence the index slide in December, they were, in fact, lawful and did not attribute to the liquid crisis. The central bank circular issued on November 28, 2010 asked banks to adjust all loans, amounting Tk 10 million and above, that have been diverted to areas other than the purposes mentioned in the loan applications by December 15. This surely put the banks in trouble as a lot of that money was invested in the share market. As a result, banks started selling shares and withdrawing money from the stock market. This was the beginning of the price-slides in December. To tackle the disaster and assure the panicked investors the central bank extended the time limit by one month for the banks for submission of the list of loans to January 15, 2011. The commercial banks were instructed to adjust such loan portfolios by February 15, 2011 instead of January 15 to ease the pressure on the money market. The securities regulator increased the margin loan ratio from 1:1 to 1:1.5 and then to 1:2. SEC also restored normal trading of Grameenphone (GP) and Marico, suspended the Net Asset Value (NAV) based margin loan calculation and execution of order relating to increased margin deposit by members of the bourses.

But that did not prevent the fall. After consecutive days of index decline, the stock market suffered from record-breaking disasters in January. According to a DSE insider, who preferred to remain unnamed, as it was the financial institutions' year closing, they had to pull off money invested in the market for balance purposes and as a result the banks were neither able to provide the 1:1.5 margin loans to the retail investors. This event caused less investment from the retail side as well. With the butterfly effect, the stock market headed towards a liquidity crunch. The liquidity crisis in the money market was one of the key factors behind the continuous slide in share prices and turnover. Like most of the market analysts, the anonymous DSE insider blamed price-correction and price re-adjustment of the financial institution stocks, which were over exposed in the capital market for drop in share prices. Along with the panicked investors who started selling shares after losing confidence in the market, the anonymous insider suspects that some syndicates created the unusual sell pressure, which would help them to purchase shares at low rates. “You see, the way the share prices were increasing last year, it would have become impossible to play the game for the syndicates at such high rates. Hence they wanted to decrease the rate and the liquidity crisis would help them to force price corrections,” he adds.

January 11- January 18:

On January 11, 2011, reversing the trend of the previous few days, DSE index ascended with a record gain of 15 percent. The DGEN stood at 7,512 points at the closing of the day's trading, recovering 1,012 of the 1,235 points lost on the preceding two days. This magic jump was not due to any divine intervention either. A stockbroker, again preferring to be anonymous says: “After the sharp and continuous falls on January 10 and 11, the government unofficially prohibited the institutions, especially the banks to sell any share. And there were few institutional buyers who backed up the market.” On this issue, Professor Salahuddin Ahmed Khan says, “January 11, 2011 was the reversal of the previous day. On January 10, the nervous syndrome led to panic sales. The government and especially the Prime Minister's instruction to Bangladesh Bank to ensure that flow of funds to the market will be easier again brought back investors' confidence for which they wanted to recap the loss they sustained in the previous days. That caused the record level upward trends in the market.” The BB and the SEC did relax and in some cases reverse some of their decisions in that respect. Though the unusually high buy-pressure pushed the index high, due to the stalemate in the buy-sell, the single turnover was very low– Tk 977 crore.

|

Investors and stockbrokers cling onto the monitors as market prices fluctuate.

Photo: zahedul i khan |

Since the nail-biting drama, the market is still dangling through ups and downs. Initiatives are being taken from all aspects: BB, SEC, and the Government to stabilise the stock market but according to Professor Salahuddin Ahmed Khan this is not happening: “I don't think the market is stabilising. As you can observe by now that the liquidity position as well and nervousness of investors are still prevailing. It will take sometime to overcome the current state of the market. Here the investors must also demonstrate some degree of restraint to overcome present difficulties.” Proving his speculations correct, the share market hit its lowest turnover in nine months on January 18. The continuously shrinking turnover stood at only Tk 8.49 billion, the lowest since April 15, 2010, and Tk 24.01 billion lower than the highest-ever record of Tk 32.50 billion, set on December 5, 2010. An official from a broker house, in condition of anonymity, says that as Bangladesh Bank has not provided any written order on relaxing the bank loan threshold of 15 percent of their total capital to their subsidiary companies, the banks are not yet confident in providing margin loans to investors and increase client exposure. Added to this, nor institutions neither retail investors are interested in buying shares with high PE ratios. The anonymous official complains that the merchant banks do have the money as they had sold most of their shares months before the slide started. They are whining about their liquid crisis just to create pressure on the Bangladesh Bank.

The have beens and the should haves

So what really went wrong? Why did the giant gas balloon, flying so high, start leaking? The wavering policies of the regulatory commission are mostly blamed by the investors. The regulator put in 83 directives during the period between January 17, 2010 and January 10, 2011. It changed the directives of margin loan ratio 19 times. “The regulators of the money and capital markets in Bangladesh are opposite in characteristics,” says Salahuddin.

The central banks all over the world are always very slow to respond. They seriously try to look before they leap. Here in Bangladesh they are similar in characteristics. They have been observing the financial institutions are crossing their limits for investment in listed securities and the actions came lately. On the other hand the SEC in Bangladesh always remains nervous. They like to feel that whatever happens to the market, they will be held responsible. So they don't want to see the market index or transaction go up and down at a high rate or beyond a certain level. Therefore they are continuously imposing new policies (forgetting that policies are long term courses of actions) and again changing/amending it in rapid succession. “In such a hectic work environment, with such poor manpower they fail to pursue one of the universally acceptable role of the securities market regulators, which is the role of monitoring market behaviour in terms of ill trading (manipulations, abnormal price movements, improper trade executions etc). Consequently, a group of market participants took advantage of the situations,” analyses Professor Salahuddin.

On what should be done to make the market less vulnerable to drastic changes and make it more secure for retail investors Salahuddin says, “The market base needs to be broadened. Newer securities like derivative products, stocks, bonds etc need to be brought, more institutional investment vehicles like pension funds, portfolio managers (not the lending based merchant banks), mutual funds, unit trusts etc need to be created. The market regulations should be done more professionally and the stock exchanges need to be demutualizsed at the earliest possible time. However, one must realise that, the capital market is a dynamic market and so it cannot remain stable. It will have waves moving ups and downs.”

Game is the Name

Farhana Urmee

Oops, you lost the game! Quit or continue? When such boxes flash on one's computer screen it might not be such a big deal for the player to stop the game that he or she has been playing for hours; it is not even that difficult to go on with the game because what is at stake are a few points.

Quitting or continuing is just a matter of clicking the right button of the mouse and does not make much a difference in one's life, as he or she is not investing any resource in the game. But when one invests, especially when it is liquid money, the question of quitting matters quit a bit.

Take Zahir, a supervisor of an apartment complex at city's Dhanmondi, who earns around Tk 6,000 a month for his job. As the number of his family members has just increased, he needs some extra earning. The search for additional income and the sight of people making a quick buck in the stock market have prompted Zahir to borrow Tk 50,000 to invest in the burse with the hope of earning a bit more. Within 48 hours of his investment, the stock market experienced a massive fall and his invested money has come down to almost less than half.

|

The search for additional income and the sight of people making a

quick buck in the stock market have prompted many to invest. Photo: zahedul i khan |

Zahir thought that his investment would be safe, and this sense of security of 'no losses' led him to borrow the amount of money that was almost eight times his monthly income. After the fall of the market, the profit from the investment has become a distant dream, and to make matters worse, he is now burdened with a huge loan. Zahir is faced with the perennial question: Quit or continue?

There are other small investors like Zahir who have invested in the stock market with the hope of seeing the prices of the share rise and are now faced with huge losses. Md Kamran Hasan. who has been in this business since 2007, quit his lucrative World Bank job, with the intention of devoting all his time to the market. He has also been hit by the recent fall in the stock market. His balance has witnessed a decline of around Tk 19 lakh.

|

Small investors should be aware of the market and its tendency to rise and fall, as often some tittle-tattle can be responsible for the direction of the curve of the market.

Photo: zahedul i khan |

Asked why he gave up a regular job and invested in the share market, he boldly says, “If I have a certain amount of idle money and if I am sceptical about investing it in any business due to many socio-political problems, why shouldn't I invest in the capital market?”

Regarding the recovery of his loss, he says that there is no way out other than take it on the chin and wait for the time when the price of his shares goes up to balance his initial investment.

While Kamran has decided to remain patient and wait for the right time to come, his wife Afreen Ferdousi is in despair as she has taken a loan of Tk six lakh from a bank to invest in the stock market. Now only one and a half lakh taka is left in her account.

Md Mostofa Rashel, a service holder in a private organisation, has been investing in the capital market since he was a student. He, however, remains safe from the hit. “During the period of market correction there is scope for the market to fall but other factors are also at work which ultimately makes some investors' accounts exhausted and help others to get rich overnight and get away from the market,” Mostofa says.

He says that many investors have believed in rumours and have invested in companies that do not have enough investment capital. “The shares of these companies which have been bought with a high price (which is not their actual price) can never reach the optimum level of expectation of the buyers, it is hardly surprising that the buyers have faced loss while selling these shares,” says Mostofa, adding that small investors should be aware of the market and its tendency to rise and fall, as often some tittle-tattle can be responsible for the direction of the curve of the market.

Again, decisions that come from the policy makers or the regulatory body should not come all of a sudden. The market should be analysed throughout the year. Bangladesh Bank ought to monitor the other banks investments in the capital market from the very beginning of the year instead of giving decisions out of the blue, adds Mostafa, who lost half a million from his prospective profit, although his initial investments intact.

Again Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) need to monitor the market regularly. When Kamran entered, the size of the market was Tk 80 crore and now it boasts a market of Tk 3000 crore. The SEC still has the same manpower as before, which is obviously insufficient, observes Kamran. Moreover the SEC needs more technical support to conduct investigations, and it should also have the power over the reasonable balance of the market, he continues.

In a country plagued with problems like unemployment, lack of investment plan and whimsical investors whose only target is to gain 'a huge profit', the index of the market gets jittery quite easily. It makes an enormous impact on the country's economy. To make matters worse, there is an insatiable desire to earn a lot of money in a short span of time, which always threatens to make the capital market a gambling board.

Myopic Investors and Irregular Regulators

JYOTI RAHMAN and SHAHEEN ISLAM

Amid signs of weakening through most of December, the bull run in the Dhaka stock market came to a screeching halt on the morning of Monday January 10, when the general index lost more than 9.25 per cent within an hour of the start of trading. This prompted the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to suspend trading for the first time in its history. Angry investors, who had already demonstrated violently a number of times in December, clashed with the police, thereby attracting the world's attention.

And then, on the following day, the market rebounded with the index rising by 15 per cent.

What happened? Why did it happen? What will happen next? What should (have) happen(ed)?

We don't pretend to have anything more than a tentative answer to only some of these questions. In a nutshell, by the end of 2010, Dhaka stock exchange was very much in the bubble zone. What happened in the second week of January could have been a bursting of that bubble. A hard landing has been avoided, at least for now. Instead of trying to guess what will happen next, let's explore how we got here, focussing particularly on the microeconomic aspects.

Fundamentals

Asset prices are said to be in a bubble territory when they are unhinged from the economic fundamentals. A few years ago, house prices in the United States and a number of European countries reached the stratosphere, even though supply and demand could not explain the boom. A few years earlier, stock prices of technology companies in the US reached levels unsupported by economic fundamentals. Both were bubbles. In both cases, the initial rise in prices could have been explained by economic fundamentals: house prices were primed for a boom in the early part of the last decade given low interest rates, and financial innovation allowed more people to enter the market than was previously possible; the tech boom owed its origin to the realisation in the mid-1990s that the internet had tremendous potential.

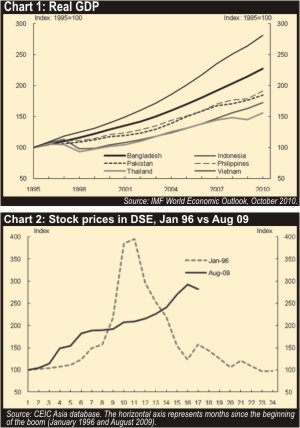

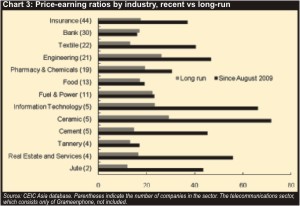

Every bubble has its genesis in fundamentals. So it has been with the Bangladeshi stock market. Compared with similar economies in South and Southeast Asia, Bangladesh has been posting remarkably stable growth since the 1990s (Chart 1). Meanwhile, with the landslide victory by the Awami League in the December 2008 election, investors had reasons to be optimistic about the political climate in the country – traditionally a key risk to investment.

Bubble

These fundamentals would have justified a bull market. And until the second half of 2009, that's what we had. However, from around August 2009, the market started to get completely unhinged from the fundamentals. These fundamentals would have justified a bull market. And until the second half of 2009, that's what we had. However, from around August 2009, the market started to get completely unhinged from the fundamentals.

From the beginning of the decade till August 2009, the direction of short-term fluctuations had been unpredictable, even though it appreciated strongly over the long run. Between August 2009 and November 2010, share prices rose every month. The price boom had lasted longer than 1996 (Chart 2). And with foreign participation in DSE being less than 2 percent, the boom has been a domestically driven one.

But how can we tell that share prices had entered the bubble territory? One way to make that call is to look at the price-earnings ratio (P/E ratio).

One of the fundamental reasons why people hold assets is because of the stream of earnings they provide. A low P/E ratio indicates that investors have not taken much risk in view of past earnings: even if the price they paid seems high, the earnings have been high enough to justify such a price. On the other hand, a high P/E ratio indicates that investors are overtly optimistic about the future earnings of such shares, and are therefore willing to pay a higher price.

Chart 3 compares the mean P/E ratios for selected sectors after August 2009 with their long-run (December 2005 - August 2009) values. With the exception of the banking sector, every industry has seen sharp rises in their P/E ratios. What fundamental changes in the economy could justify the rise in P/E ratios in so many sectors to such extent?

Myopia

Interestingly, the industries with the smallest numbers of publicly-traded companies have tended to post the largest increases in P/E ratios. This suggests that the increases in sectoral P/E ratios may have been driven by a handful of well-performing shares. Did the future profitability of the firms concerned increase that dramatically that quickly? Or did these prices rise on the back of word-of-mouth among myopic investors?

Let's think through the myopic investor idea with some examples.

Suppose one had invested 100 taka in DSE in January 2002. Five years later, it would have been worth 240 taka solely through capital gains (that is, without accounting for dividends and brokerage fees) – an annual rate of return of 19.2 percent, significantly higher than what most deposit schemes pay. On the other hand, the value of the investment over the course of 2002-03 was much more unpredictable. Initially it rose, and then it fell such that the 100 TK had barely appreciated if one were to liquidate in March 2003.

|

After the bubble burst. Photo: zahedul i khan |

The point we want to drive home is simple: up until August 2009, the stock market was a tricky place for investors looking for short-term gains, but a beneficial place for investors willing/able to invest over longer time periods.

What happened after August 2009? An unprecedented good run in which the index appreciated every month until November 2010, with the largest percentage increases in late 2009 and early 2010. An investment of 100 taka would have only increased in value in this period, and not decrease once (until the very end).

Suddenly, the stock exchange became a good place for short-term gains. This in turn attracted more short-term funds, and the volume of trade on the Dhaka bourse increased as a result. In the meantime, the number of retail investors who typically invest in a small number of shares went from less than 500,000 in 2006 to almost 3.5 million today. In just the first 10 days of February 2010, nearly 125,000 such trading accounts were opened.

Most of these retail investors have very little, if any, experience of a bear market, let alone a crash like the 1996. Indeed, the younger investors who reacted violently on 10 January would have been in their teens during the last bubble. Moreover, unlike institutional investors, anecdotal evidence suggests that the individual investors rely less on analysis of the fundamentals and trade more on personal advice from brokers or fellow investors. One can easily imagine how a small number of such investors buying a particular share could lead to other investors jumping on the bandwagon and bidding the price of that share through the roof.

Incidentally, one industry where the P/E ratio has fallen relative to the long run is bank. It's possible that this shows the preponderance of large institutional investors in this sector. Such investors are likely to rely more on fundamental analysis than short-run herd behaviour, and are likely to enjoy superior information regarding the banking sector and its business models.

Regulators' irregularity

Investors usually buy/sell shares by putting down only a fraction of the money needed for investment, with the rest being borrowed from brokers or merchant banks. The maximum that can be borrowed is a percentage of how much they put down. This percentage (also called margin loans) is usually determined by the SEC.

In February 2010, with the bubble in full swing, the SEC ruled that the maximum that can be lent was 150 percent of the investor's down payment. Thus, if we wanted to buy a stock worth100 taka, we would only have to put down 40 taka of our own money and could borrow the other 60 taka (150 percent of 40 equaling 60). Such loans could not be given against stocks with P/E ratio of 50 or more. This made short-term investing much easier and much more prone to moral hazard problems, as more than half the investment could be made with borrowed money. In February 2010, with the bubble in full swing, the SEC ruled that the maximum that can be lent was 150 percent of the investor's down payment. Thus, if we wanted to buy a stock worth100 taka, we would only have to put down 40 taka of our own money and could borrow the other 60 taka (150 percent of 40 equaling 60). Such loans could not be given against stocks with P/E ratio of 50 or more. This made short-term investing much easier and much more prone to moral hazard problems, as more than half the investment could be made with borrowed money.

By July it had become much clearer that the market was over-valued. The SEC tried to push on the brakes, but not hard enough. It deemed that the margin loans could be a maximum of 100 percent of the down payment. Even then, a short-term investor would be using only half their own money for investment. Their “skin in the game” had increased, but was it enough?

As it happens, apparently the SEC did not think so. Within four months, it squeezed the margin limit further to 50 percent of the down payment, provoking angry reactions from retail investors late last year. Within three weeks thereafter, it had loosened the requirement back to 100 percent, and 5 days after that, back to 150 percent in the face of investor ire and a market-wide liquidity crunch, as institutional investors such as banks withdrew money from the stock market.

Even then, evidence suggests that most brokerage houses and merchant banks were not lending up to the maximum margin, suggesting that at that point a minimum margin requirement would have been more apt.

The SEC's actions thus seemed largely reactive to market developments, rather than anticipatory or even contemporaneous.

The SEC was not, however, acting in a vacuum. The macroeconomic context of the boom has been one of easy money. And the political economy of the boom has been framed by the fact that the party presiding over the last crash is in office now.

How did these macro and political economic factors fuel the bubble? And what should happen now? –These are the questions that have remained to be explored.

Jyoti Rahman and Shaheen Islam are economists and bloggers (www.unheardvoice.net/blog).

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |