| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 15 | April 16, 2011 | |

|

|

Cover Story The Journey of Challenges and Hope Bangladesh has celebrated its 40th anniversary of Independence on March 26 this year. In the same year The Daily Star celebrates its 20th anniversary. Starting as a brand new English daily in the year that democracy was restored to the country, The Daily Star has been witness to the most momentous events in the last 20 years. This special issue of the Star highlights the way The Daily Star evaluates the nation's progress in these two decades. In Grateful Memory

The Daily Star story Mahfuz Anam

It was Sunday January 13, 1991. Excitement was in the air throughout the day in our modest Motijheel office. All sorts of last minute retouches were being put to the paper's layout that had been weeks in preparation. Earlier we had set up what could then be termed as a plush production section with 10 Apple computers (with all of 10 megabyte memory and 1 mb RAM) and the only air conditioner in the office. We were told these wonder machines had to be kept cool and dust free, even though all the rest of us, even the not so young editor, would suffer the sweltering heat and dust. Press, where we intended to print, belonged to the defunct weekly Dialogue located in Karwan Bazar, (where nine years later we were to shift our office). Frantic calls were being made to distribution agents both in Dhaka and outside to persuade them to place higher orders for our first edition. It totalled 10,000 and we felt we were off to a good start. As evening drew near, nervousness began to overtake excitement. Earlier my first ever meeting with the hawkers was held, organised by Towfiq Aziz Khan, a veteran of many decades of newspaper management. The media scene was far different than today's. Most of the well-known newspapers of today did not exist then. There were no private TV channels and no private radio. There was no mobile phone and no Internet. There was also no cable television. The only channel we saw was our good old BTV. And of course there was no traffic. As the machine rolled and one by one the very first issues of The Daily Star came out of the cutting blades and on to the display board, my eyes became watery and I could no longer hold back the drops of tears that began to roll down my face. Shaheen, my wife and the source of inner strength that energised me all through, pressed harder my hand that she was holding from the moment we went to the press to witness, what was for me the realisation of a long held dream. I immediately called Ali Bhai and excitedly told him how impressive the paper looked. We exchanged mutual congratulations. It was hard for me to pull away from the printing machine that was churning out my dream for which I tuned topsy turvy the life that my wife and two children were leading. Very early next morning I accompanied our circulation manager to most of distribution points and saw how the hawkers were picking the papers including ours for distribution. Thus began a journey twenty years ago that ended up producing the best English daily in post independence Bangladesh. After years of planning while Ali Bhai ( S.M. Ali) and I were in Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok, respectively, and following months of dummy printing, The Daily Star was finally emerging as something real. My proposed name was the Independent but Ali Bhai preferred The Morning Star. But we soon learnt that it was the name of the British Communist Party paper and quickly changed to The Daily Star. Ali Bhai retired from Unesco and I resigned from the same organisation and we both returned to Bangladesh to start The Daily Star. It was Mahmud Bhai (AS Mahmud), the founding Managing Director of the Mediaworld who played the most important role in bringing the Board together. Rouf Chowdhury, Latifur Rahman, Azimur Rahman (founding chair) and Shamsur Rahman were all either his business partners or colleagues or very close friends. It was of course Ali Bhai's magnetism, elegance, huge experience and leadership that impressed the Board and got us started.

History seems to have beaconed our birth. After nearly a decade of Gen. Ershad's autocratic rule a united movement of the people demolished it, which fell on 6th of December 1990 and we were born on the 14th of January, 1991. The air was pregnant with the promise of momentous changes and full of hope and expectation for a renewed Bangladesh well in line with the spirit of our Great Liberation War. There couldn't have been a better moment for the start of a newspaper that was determined to fight for democracy, press freedom, people's rights, transparent and accountable government and rule of law. My first piece in the inaugural edition of the paper was titled “Dream Reborn” which was full of expectation and hope of a Bangladesh full in freedom, determined in purpose and vigorous in action, all leading to a development momentum that would see us restored n dignity in the community of nations. Three momentous events tested our young team's professionalism. The Kuwait invasion by Saddam and the consequent invasion by the US, the devastating cyclone of 1991 and the holding of the first free and fair election for the first genuinely elected government after the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in August 1975. Within less than six months into our existence we ran into our severest staff crisis. Twenty-six senior colleagues, in fact all heads of department except sports, left us to publish a new paper called The Telegraph. It coincided with a sudden eye disease of Ali Bhai that needed for him to go to Bangkok. I recall the most dramatic events as resignations kept pouring in as Ali Bhai's Thai flight took off. When I called him later in the day at Bangkok hospital Ali Bhai's wife advised me not to tell him as ailment of the eye has a lot to do with tension and anxiety and the news I had to give him would definitely exacerbate his condition. This exodus of 26 senior colleagues some of whom were highly regarded and hugely experienced and the consequent entry of more 35 fresh University graduates and first time job holders changed the demography of the newspaper's staff and lies at the core of its future success. These young, eager, energised, hard working, socially-committed and eager-to-learn individuals, some of them highly talented, brought about a freshness in the paper that others at that time lacked. But of course their lack of experience and maturity made us extremely vulnerable which the dexterity of Ali Bhai's leadership helped to overcome. As we struggled to prove our worth another reality hit us hard. Our calculation of the growth trend of an English newspaper proved to be totally wrong and so was our calculation for the fund needed to push its growth. Within six months all our financial calculations went haywire and both Ali Bhai and I saw the imminent exhaustion of funds. I remember entering Ali Bhai's room extremely gloomy and being energised by his pep talks and getting back to work.

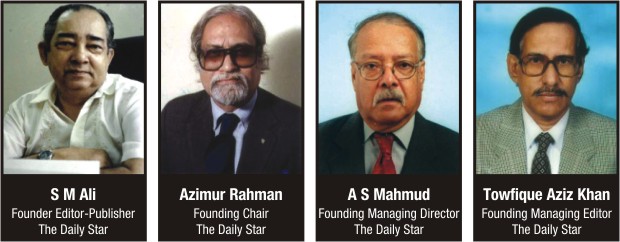

To face the financial crunch the first thing we needed to do was to cut costs. So we shifted from our Motijheel office which was costing us two lakh taka a month in rent, to a house in Dhanmondi Road 3 at Tk 35,000. Both Ali Bhai and I were shy to appraise the Board fully of the miscalculated projections but when they came to know of it, they extended loans to the paper and advertisement support that met the immediate needs. It was about two and half years into our existence that the most severe misfortune befell the paper. Ali Bhai was diagnosed with cancer in mid 1993 and passed away within a few months, in October. The staff were devastated and the Board no doubt worried. We were then a small, financially struggling paper with a group of young, vibrant but mostly inexperienced colleagues. The man whose wisdom, vision, strength, experience and charisma were our biggest assets and whose leadership was our only way forward suddenly was no more. I was far from worthy to replace him. Except for sincerity, eagerness and determination I had nothing to match Ali Bhai's enormous capacities and even greater humaneness and sophistication. He was the only Bangaldeshi ever to be the Managing Editor of Bangkok Post and Hong Kong Standard and be the Executive Director of Press Foundation of Asia, Manila. He was highly respected figure in Southeast Asia, and many of their iconic media figures were his protégées. We had scheduled a roundtable in partnership with an UN Agency on the day he passed away in Bangkok. I moderated till the end, and then shared the sad news and broke down crying. My greatest test was at hand. On the occasion of our 20th anniversary I would like to recall with pride and gratitude the role played by our founders who are no more. Azimur Rahman never wanted to be in the media business but fell in love with it from the start. He liked its capacity for social good and admired its ability to point out the rights and wrongs of the day and seek immediate redress. He was a wise founding chair and defended firmly the independence and freedom we needed for our journalistic work. A.S. Mahmud had an intuitive affinity for media. He was the principal organiser of the Daily Star board and its driving spirit. He loved the paper and worked relentlessly for its growth. Towfiq Aziz Khan was the quintessential gentleman in the print management world at that time. Originally a sports journalist he shifted to the management side and was the main person who set up the structure of the paper. He recruited most of the non-journalist staff and set up the management structure that stood us in good stead. On this auspicious occasion I would like to thank Mediaworld board but for whose vision and delegation of administrative and financial authority the Daily Star could not have come where it has. Their fundamental adherence to the principles of free press and independence for the editorial office was extraordinary and their insistence on financial discipline and transparency was vital for the paper's standing. I will be failing in my task if I do not thank our advertisers and patrons who have stood by us through thick and thin. My grateful thanks goes to my beloved staff members whose commitment, diligence, pride in the profession and above all honesty lies at the core of this paper's success. My final debt of gratitude is for our readers. A paper's readers are its life-blood. We exist because we are read. The day our readers reject us, however big our money-bag is, we cease to exist in a journalistic sense. Therefore thank you readers for not only keeping us alive but nourishing us with ever more guidance and support. The writer is Editor and Publisher of The Daily Star. Politics Twenty years of Politics in Bangladesh Syed Badrul Ahsan The collapse of dictatorial rule in Bangladesh in December 1990 was but a renewal of the old historical lesson that the yearning for government by the consent of the governed had grown into a habit for the Bengali nation. In the twenty years since that huge fall of autocracy, not all of the dreams the people of Bangladesh forged in that struggle for pluralism may have come to fruition; not every ambition may have been fulfilled. Indeed, the basket of disappointment may appear too surfeit with realities we could well have done without. And yet since the return of elected government through the general elections of February 1991 there has arisen the sure feeling (and it is a feeling which endures) that democratic government is an idea which needs to be sustained in the larger interest of the future. In all these two decades, a time in which this newspaper has come to life and youth, politics has passed through the many crannies and nooks in order to reach a state of being that could be truly construed as satisfying. Yet satisfying, in that larger sense of the meaning, it has not been.

The journey, nevertheless, has gone on. It all began in that euphoric moment when the political classes, symbolised chiefly by the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, came together to guide Bangladesh back to parliamentary government in mid-1991. The moment was pivotal, considering that the country had, since January 1975 (as a consequence of the Fourth Amendment to the constitution) operated along the lines of a presidential form of government which again took newer forms and substance along the way. From such a perspective, a return to parliamentary politics, which again was the principle set in place soon after liberation in December 1971, made sense. The move ought to have led to more substantive ones, especially in terms of making the Jatiyo Sangsad truly effective as a body. As time went on, however, it began to be made clear that the presidential form had in more ways than one been supplanted by a prime ministerial system. As if that were not enough, the political unity that had been forged between the political parties in the course of the struggle against the Ershad regime soon began to come apart. The eventual break between the BNP and the Awami League came through the badly managed by-elections in Magura in 1994, where clear instances of vote rigging gave the Awami League reason to take its politics from parliament and into the streets. The bipartisan turn that was expected of democratic politics did not happen. And politics swiftly took a turn for the confrontational in place of the envisaged consensual. Magura impelled the opposition Awami League into demanding that future elections be held under a caretaker government, a call the ruling BNP quickly dismissed out of hand. The AL stayed out of parliament and so helped reduce the House into a pointless body. It then became the task of Sir Ninian Stephen, as ordained by the Commonwealth, to attempt his hand at mediation, the better to have the parties reach middle, agreed ground on the shape of future politics. In the end, in 1995, the move collapsed. By early 1996, the ruling BNP was ready for a fresh spate of general elections as its five-year term drew to a close. For its part, the Awami League was determined to ensure that the elections were held under a caretaker government. In February 1996, the BNP went through the motions of an election, boycotted by the AL, and claimed victory as it prepared for a second term in office. The move led to a crisis as the Awami League and the rest of the secular opposition went into action to force the government from office and for fresh elections to be held under a new caretaker government. And for the first time since March 1971, when the civil administration in what used to be East Pakistan came together in solidarity with Bangabandhu's demands for a transfer of power from the Yahya Khan military regime to the political leadership elected at the December 1970 elections, large sections of the bureaucracy linked up with the Janatar Mancha. By the end of March 1996, the BNP, having agreed to hand over power to Justice Muhammad Habibur Rahman and his caretaker administration, quit office.

Fresh new elections were scheduled for June 1996, but along the way certain hiccups pointed to the fragile nature of democratic politics in the country. President Abdur Rahman Biswas sacked the army chief, General Mohammad Nasim, and replaced him with General Mahbubur Rahman. At the elections on June 12, the Awami League, led by Sheikh Hasina, returned to power twenty-one years after Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated on August 15, 1975. The Awami League's return to office remains significant for quite a few reasons. One of the first acts it undertook was the repeal of the notorious Indemnity Ordinance (which had been incorporated in the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution by the regime of General Ziaur Rahman in 1979) as a way of tracking down Bangabandhu's assassins and bringing them to justice. Soon after the repeal, the trial of the assassins (those who happened to be in Bangladesh at the time) commenced and judgement would be delivered in November 1998. The government also concluded a water-sharing deal with India that promised a flow of water to Bangladesh commensurate with its needs during the change of the seasons. A landmark move by the government was the agreement it reached with the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Sanghati Samity in the Chittagong Hill Tracts over an end to the long insurgency. The deal envisaged a return home of those among the Chakma community taking refuge in India as well as a withdrawal of army camps from the region. Of course, the agreement aroused the ire of the opposition. By and large, though, it was looked upon as a substantive step towards a restoration of normalcy in the region. It was rather a surprise for many across the country when it lost the general elections held in October 2001. But then, there were all the palpable reasons behind the electoral collapse. The share market scam, the Tipu Sultan episode, the home minister's lathi procession explain the debacle. The return of the BNP and its allies to power were soon to prove a difficult affair for the country in that supporters of Begum Khaleda Zia swiftly went into action against members and followers of the defeated Awami League and members of the Hindu community. Worse was the inclusion of the Jamaat-e-Islami in the cabinet. The move was stunning for the secular camp for the particular reason that the Jamaat had been a vocal, active supporter of the Pakistan occupation army and stood accused of killing and helping to kill a large number of Bengalis, particularly leading intellectuals of the country on the eve of liberation in 1971.

The period of BNP-Jamaat rule was marked by a clear decline of democratic politics through the emergence of Islamic militancy in the country. Such outfits and the JMB and HUJI saw little hindrance to an expansion of their activities, with the result that a wide network of fundamentalist terror came to envelope the country. Curiously enough, the government remained in denial mode and remained content to point the finger for all the trouble at others. A foretaste of what was to come was noticed early on during the BNP-Jamaat period when the authorities took some eminent citizens – Professor Muntassir Mamoon, politician Saber Hossain Chowdhury and Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee personality Shahriar Kabir – into custody on flimsy, false charges of having been behind a string of bomb blasts in several cinema halls in Mymensingh. These men were placed on remand and subjected to unprecedented torture and humiliation. It was but the beginning of a dehumanisation of politics, a process that was to be maintained by the caretaker government that took charge in early 2007 and carried on by the Awami League after it returned to office in late 2008.

Politics clearly hit rock bottom on August 21, 2004 when a series of explosions at an Awami League rally in Gulistan left 22 people, including senior party leader Ivy Rahman, dead. Scores of others were injured. In the aftermath of the attack, what should have been a credible inquiry into the incident turned into a farce, with a one-man inquiry committee headed by Justice Joynal Abedin pointing the finger for the horror at unnamed foreign powers. A scapegoat, in the form of one Joj Mia, was charged with the crime and put behind bars. Such moves left few in any doubt about the intentions of the government. A year later, a series of simultaneous explosions in 63 of the 64 districts of the country left the country convulsed with shock and with the feeling that the government was incapable of handling the militants. Then too there was the grave incident of ten truckloads of arms being intercepted in Chittagong, which raised all sorts of legitimate questions about the involvement of certain government functionaries in the whole shady deal.

If the BNP-Jamaat government proved unable or unwilling to rein in militants and other destabilising forces, it proved equally inept in handling politics and constitutional matters. Despite public outrage, it placed Justice M A Aziz at the head of the Election Commission. The result was a long list of fictitious voters, an act which quickly spiraled into a movement by the political opposition for a fresh Election Commission. By the end of its term in office in October 2006, the BNP-Jamaat government had not conceded the demand. It simply handed over charge of the country to a partisan caretaker regime headed by President Iajuddin Ahmed, who set January 22, 2007 as the date for new elections. The caretaker government was forced from office on January 11, 2007 against a background of increasing opposition to any election being held under Iajuddin Ahmed's stewardship. What would come to be known as 1/11 came to pass, with the army playing a definite role in the background. On the strength of a state of emergency, a new caretaker government, this one headed by Fakhruddin Ahmed, a former governor of Bangladesh Bank, swiftly went into action against corruption in politics, hauling a large number of them to prison. Politics was put on hold as the government sought to practice what would come to be known as the Minus Two formula, whereby Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia would be eased out of politics and a process of reforms within their parties would then throw up new leadership in the parties. In the event, the move would end in disaster for the government as supporters of the two leading politicians rallied behind them and clearly made known their refusal to have anything to do with the reformist agenda in their parties. The good bit about the Fakhruddin caretaker administration was that it began well, with considerable public support, and appeared headed toward accomplishing the kind of political reforms that would transform the face of national politics. The not so good bit came in its slow unraveling as demands grew for elections to be organised and the country returned to democratic rule. In late December 2008, new general elections brought the Awami League, with its allies, back to power with a three-fourths majority in the Jatiyo Sangsad. The BNP and its friends were left licking their wounds.

Two years after the elections, what are the achievements that the government can cite as part of its record? To its credit, it was able to complete the trial of Bangabandhu's assassins and see five of them (the others remain absconding abroad) go to the gallows. Equally important has been the judicial decision annulling the Fifth Amendment to constitution, which has meant a de-legitimisation of all regimes which held office in Bangladesh between August 15 1975 and April 1979. It has also signified a return to the secular spirit enshrined in the constitution as it was enacted in 1972, though to what extent the government means to put that spirit in practice remains a question in light of its assertions that the Bismillah factor will remain a part of the constitution. In the midst of it all, tragedy struck the nation once more. In February 2009, barely 50 days into the inauguration of the Awami League-led government, a mutiny by jawans of Bangladesh Rifles left 57 army officers, including the director general, Major General Shakil Ahmed, dead. The trial of the mutineers is going on. Barring the above, politics has clearly gone back to the adversarial state it has traditionally been in. The BNP, in opposition, has remained outside parliament. The ruling party appears to be in little mood to indulge it. Meanwhile, the country remains busy with preparations for a trial of the war criminals, namely, local Bengali collaborators of the Pakistan occupation army in 1971.

ECONOMY Getting over the Stagnation Hangover Inam Ahmed The economy at best can be described as still trying to recover from the hangover of the 'decade of stagnation' emerging sluggishly from a long rule of dictators and pseudo democrats. If we start from 199I, the year when when Bangladesh embarked on a new journey of democracy after the fall of General HM Ershad who ruled the country for long nine years after seizing power through a coup, the economy still desperately needed foreign aid to fund its development programme. It was still pretty much a dictated economy that still needed urgent reforms.

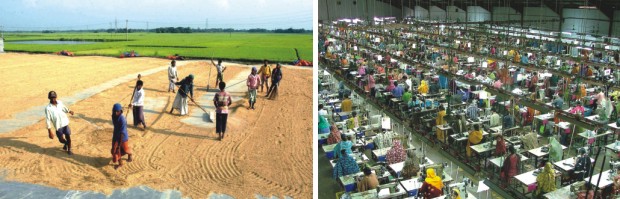

It was a time when entrepreneurs were struggling to get a foothold on the global market. Export items were few with jute leading the basket. If demand for gunny bags used in wars dropped foreign exchange reserves would plummet. The garment factory owners often vented their frustrations contending that, given half a chance, they could clock exports worth $1 billion a year. Unfortunately their claims were most often than not looked on with skepticism. Industries were few and far between, with the government sector leading the pack. The industrial indices looked up at the state-owned sectors to see any northward movement.

The fiscal situation remained bleak with no sign of reforms in sight. Taxes were hard to come by and revenue-GDP ratio was one of the lowest in the region. The money that could be had through fiscal measures could hardly cover the revenue expenditure. Every few months, the government would devalue the taka in the hope of increasing exports, creating more jobs.

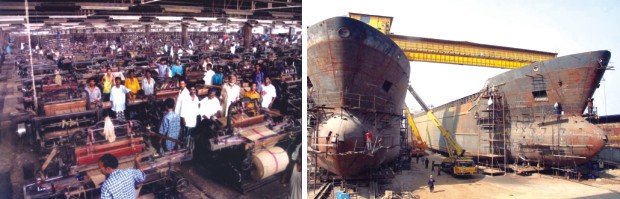

It became a common scene every year, for the government to trudge to the donors in Paris at what was known as the Paris Club meeting and beg for more aid. The donors would then read out a long litany of pledges that the government had promised but could not live up to. New sets of conditions would be laid down if any assistance was to be expected. The finance ministers would nod their heads in agreement and come back with a grim face knowing fully well that again, most of the new promises would remain unfulfilled. How could they chop off the workers in state industries? How could they privatise agriculture input service? How could they let the wheels in the jute mills stop? How could they make the state-owned banks free from labour unions and make their management free? They had no better choice as still 60 percent of the development money came from them. And growth was elusive. It was hovering in the arena of 4 percent. Finance ministers talked of the possibilities of 5 percent growth if things went fairly well. Poverty was widespread. Over 60 percent lived below the poverty line. And inequality was gaping. But then the wheels turned. And with that the economy. For the first time, GDP growth crossed that magical 6 percent figure. The public sector industry was downsized and the private sector took over. Exports increased. The garment sector that once dreamt of a $1 billion earning is now churning out ten times the amount. Exports have diversified. Once known as the producer of cheap t-shirts, top brands like Gap are now placing orders here. Japan has added to the list of export countries. Exports diversified also. Ice-class ships are being built here and exported. Revenue increased slowly yet surely.

Most interestingly, in the last 20 years, poverty has been reduced by one percentage point a year and the middle class has grown. This has spurred spending and a host of whole new range of small and medium enterprises have sprung up. And eventually the economy went through a structural change. The country that was once so dependent on aid became intensely integrated with the global economy and trade became its mainstay. The private sector took the leading role in growth generation. Share of agriculture in GDP shrunk from 19.5% in 1999-2000 to 15.5% in 2010. Industry's share rose to 17.8% in 2009-2010 from 15.4% in 1999-2000 and service sector emerged as the largest chunk with over 50% contribution. The country is now poised for a takeoff. Only it needs to match its internal dynamics with the superstructure (what does this mean? please explain a little). There are a few challenges to be scaled. The impact of climate change may be listed as the next big issue. Food security and urban congestion will be interlaced with the environmental challenge. Meeting the energy demand and productivity enhancement will be crucial for the economy to remain competitive. Narrowing the rich-poor gap and dealing with the regional disparity will be the essential tasks. But then Bangladesh has performed many miracles against the greatest odds. With the right leadership, it can turn the next decade into an age of a steady, steep climb. The writer is Deputy Editor, The Daily Star (Internet Edition). Urbanisation Twenty years of urbanisation Morshed Ali Khan

About eighteen years ago I lived in the last house of the city in the north-western direction. The third floor apartment on road No. 12 of Adabar Baitul Aman Housing offered immense joy for the family. On one direction the Dar es Salam mosque, a replica of the great Taj Mahal, reflected its petit grandeur in the clean water, visible from our small apartment all the time. On another side, the vast low lying area of Kalyanpur and beyond offered an absolute relief to the eye. An age old banyan tree in the middle of nowhere stood vigilant, sheltering thousands of birds in its complex quarters spreading all around. Once a year, sadhus from unknown places converged under the tree and sang songs till late in the nights. Under the kerosene lamps their faces emitted a glow of peace and hope. As evening fell, Adabar became quieter. Families with children took strolls on the roads and into the fields. A big pond near our building provided the construction workers ready facility for bathing and washing. Every day in the evening day labourers from Mymensingh and other districts sat down to sing songs in their makeshift abodes. The one thing that brought our family together every day to the narrow balcony was the sunset in rainy season. At times the sky would become a veritable canvas where nature mother would unleash millions of colours and shades in the most dramatic way. Then the countdown to the nor'wester from the northern skies as it brewed and precipitated to attack the city from the horizon. Eighteen years later, Adabar is unrecognisable. Every single plot was filled up to the brim with concrete and bricks and blatant disregard to aesthetics, Adabar is an absolute slum, a concrete slum to the word. On every road, from one end to the other two six-storey “walls” does the ugly revamping of the area. There is not a single open space other than the narrow roads. The housing society officials, long ago, ate up the designated playgrounds and other decent things they had promised to lure buyers buy a chunk of land. The only thing they have safeguarded for the community is the mosque but that too is surrounded by shops.

Vision does not travel far in Adabar anymore. The pond, the low lying areas and the giant banyan tree are long gone, forever. Rows of six, seven, nine and twelve-storey buildings, with the upper floors increasingly leaning towards the narrow streets, make the area even more ghastly. There is no space between any two buildings. From the street the small balconies at each apartment displays an assortment of faded colours with clothes hanging from lines. The growth of Dhaka city, which is roughly about three kilometres per year, is remarkably similar to Adabar's tangent development over the decades. Every neighbourhood has swollen in such haste that nobody knew exactly how to cope with. Titas Gas people complained, electricity supply men gave up, water men nearly drowned within their choked-up sewerages and the planners, sitting in the Rajuk Bhaban, thrived on the massive irregularities draping the city. In the old part of the city hundreds of heritage buildings were pulled down to be replaced by multi-storied blocks, most incredibly leaning towards the narrow streets by several feet. The phenomenal demand for new spaces for a booming population and economy within the last twenty years has pushed all limits to the brinks. In the decades the race between growth and governance has been decisive. Growth overpowered all mechanisms of governance and unleashed a seemingly incurable blow to institutions, organisations and political and social structures of the metropolis.

The most remarkable change to Dhaka started to happen with the arrival of mega real estate developers. Along with new arrivals came on the stage influential individuals. The lucrative real estate ventures attracted politicians, bureaucrats as well as other people holding many other key positions in the society. Ethics was replaced by “quick cash” and morals disappeared into thin air. Peripheral villages were swarmed with notorious middle men. Unleashed by their employers sitting in posh offices the middle-men were ruthless invaders. Poor villagers, mostly farmers, were forced to sell their agricultural land to the company. Those who refused to submit, were subjected to threats, intimidation, false cases, assault and even murder. The periphery of the city, vast low-lying flood plains and agricultural lands with hundreds of natural canals soon became parts of these unauthorised projects. Day and night barges laden with sand, extracted from the rivers Meghna and Dhaleshwari unloaded cargo on the flood plains and filled them up rapidly. No law could deter the tide of this development. The Wetland and Open Space Protection Conservation Act, 2000, Bangladesh Environmental Protection Act, 1995, Building Construction Rules, 2007, and Private Housing Project Land Development Rules, 2004 were defied with total impunity. New satellite townships like that of today's Adabar came into being. Dhaka's population steadily grew to around 13 million from around seven in 1991. A class of nouveau riche emerged out of nowhere. New banks opened up their doors for car, home, education and even marriage loans. Land prices soared to new heights. City streets became jam-packed to the point that movement became extremely difficult. Slums were deliberately burnt down and dwellers chased away to make room for multi-storied buildings without much regard to facilities like parking or open space. Playgrounds and public parks disappeared to the tide of growth. Consequent changes in social behaviour became remarkable. Law and order deteriorated. Congested living, restricted movements, soaring prices of essentials and lawlessness played havoc on social patterns. Impatience and aggressiveness gripped the road users. Unnecessary honking became so rampant that noise pollution has now reached a decibel level that defies all norms. Hospitals are now swarmed with patients suffering from heart ailments, diabetes, respiratory problems and gastrointestinal diseases. The obesity of Dhaka started to choke its own people – the biggest asset and the only positive aspect of our city. Change became inevitable. Suffocated and unable to move on the streets, successive governments and the civil society started talking about easing traffic jams and forcing tall buildings and markets to make room for parking spaces. The good news is the policy makers are now talking about the man-made urban nightmares and possible ways of overcoming from them. The biggest step probably came with the announcement of plans for capital dredging to restore all major rivers including the four rivers around the city. Following a High Court order in 2009 the four district commissioners of Dhaka, Narayanganj, Munshiganj and Gazipur have prepared a huge list of encroachers on the four rivers. Eviction of the encroachers are now underway. Despite a humungous negativity in the growth of the metropolis within the last twenty years, people have not sat idle. The city witnessed a boom, too, in its immensely rich cultural arena. Short films fetched international awards, stage theatre has entered a new era of hope and all other cultural activities have reach all time high – thanks to an immense vibrancy of the teeming millions. The writer is Special Correspondent, The Daily Star. Environment The Countinuous Onslaught Looking at environmental degradation over the last two decades Pinaki Roy

Bangladesh is a very common name uttered today if it is about climate change. The small country with a huge population has already helped to coin the name 'ground zero' of climate change as millions of people from here are exposed to danger. Climate change was unknown to the mass people in Bangladesh until the IPCC released it's fourth assessment report in 2007. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in their report states that 'climate change is irreversible'. It portrays so a dire situation of the country, it is unimaginable that how people will live here after 50 years or so. Climate change is a very global thing. Bangladeshi people are not responsible for this global cause for what it is already suffering or going to suffer immensely. But how much have the people of this country really cared about the environment in the last decades? In the last two decades the country experienced massive environmental degradation as different economic development activities took place here. Bangladesh is apparently now in the grip of all sorts of pollution, like air pollution, soil pollution, water pollution and what not due to mainly human activities with one or two exceptions. Mud slides in the hilly region especially in Chittagong and Cox's Bazar have become almost regular event during the monsoon due to rampant hill cutting ignoring the warnings of the geologists. Natural calamities like floods, cyclones and tidal-bores also result in severe socio-economic and environmental damages. Dwellers of the urban areas are the worst sufferers of the environmental degradation. Indiscriminate industrialisation in Bangladesh over the past decades has created significant environmental problems. That the capital Dhaka is going to be a dead city in the near future is not anymore a matter of debate. It's more a question of when it is going to be.

In the last twenty years, a convergence of unregulated industrial expansion, rural-to-city migration, encroachment of the rivers, overloaded infrastructure, confusion about the institutional responsibility for the quality of Dhaka's water bodies. In fact weak enforcement of environmental regulations has all taken their toll on surface water quality. The excessive use of groundwater made the ground water table declination in a rate of two to three metres yearly in the capital. Outside of the capital the scenario of groundwater is even worse. In the rural Bangladesh groundwater arsenic contamination is reported to be the biggest arsenic calamity in the world in terms of the affected population. The Gazipur sal forest area has turned into an illegal industrial zone while almost all the wetland in and around the capital have been developed to a residential area. Slowly, the rivers in and around the capital have turned in to a flow of filthy black water with heavy stenches. The successive governments had many pledges about protecting environment but the implementations in the field level were negligible. Lack of foresight of the policy makers coupled with corruption at the institutional level made the situation the worst ever in Bangladesh where around 160 million people live in only 144000 square km of area. The fourth IPCC report predicted, the poorest will be the hardest hit. Climate change is already affecting the ecosystem, agriculture, fisheries, health and livelihoods of millions of Bangladeshis. By 2050, 70 million people could be affected annually by floods; 8 million by drought; up to 8 percent of the low-lying lands may become permanently inundated. It is visible in all aspects of climate, making rainfall less predictable, changing the character of the seasons, increasing the possibility of extreme weather events like flood, cyclones to hit more often with great severity. One of the most recent cyclones, Cyclone Sidr, hit Bangladesh on November 15, 2007 with terrible intensity. Winds of 220-240 km/hr and the cyclone's width of 600 kilometers caused over 4,000 deaths and projected costs of $2.3 billion dollars due to widespread devastation to houses, infrastructure, and livelihoods. Still thousands of people are living on the embankment as their homestead inundated by saline water following the hit of cyclone Aila.

The sea level is rising. The lowest anticipated sea level rise is 40 centimetres by the end of this century which could be up to one meter or more. A study of Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) shows yearly around .78 mm of water is increasing at the Hironpoint of Sundarbans. Scientists predicted, around 17 percent of the landmass in the coastal zone might be inundated by the end of this century, an event that would leave around 20 million people homeless. Bangladesh has played very minimum role in global warming with a per capita .03 tonnes of carbon emission against above per capita 50 tonnes carbon by the citizens of developed countries. But the country is facing the worst climatic catastrophe in its history as a result of global warming. Climate change will change the physiography and demography of Bangladesh. Climate Change is no longer only an environmental issue; it is a development issue.

The rivers Most rivers that are still flowing through the country have lost their navigability due to sedimentation as the water flow has decreased due to extraction of water and building dams and barrages in the upstream by the Indian government. Not very long ago, water transport was the main mode of transport especially to carry goods. There was as long as 24,000 km of river routes in the country. It has come down to 6000 km now due to the loss of navigability. The decrease of the sweet water flow in the rivers has caused saline intrusion which is already another great problem for the country's coastal area.

In the urban areas especially in Dhaka the rivers, canals were significantly polluted in the last two decades due to industrialisation while land grabbers filled up rivers and canals in and around the capital. Industrial pollution accounts for more than 60 percent of the organic pollution load in Dhaka for unplanned industrialisation clusters located along the major rivers. As a result, pollutant levels in the groundwater are increasing. The pollution level is so severe that the Buriganga, Sitalakhya, Turag the main three rivers in the capital turn biologically dead during the dry season. Forest and Wildlife Realising the alarming situation of low forest coverage, the government has set a goal to increase the forest coverage to 25 percent by 2015. But the results have been far from satisfactory. The total forest covers 2.52 million hectares which is 17.08 percent of total 14.75 million hectares in the country, according to the web portal of Bangladesh department of Forest.

In reality the coverage has gone down to 7.29 percent (1.08 million hectares) according to a joint study by Bangladesh Space Research and Remote Sensing Organisation (SPARSO) and the Department of Forest in 2007. The 7.29 percent coverage includes the forest of Chittagong Hill Tracts, sal forest, mangrove forest, bamboo or mixed forest and rubber plantation. The forest of Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Sundarbans cover the two-thirds of total forest coverage in Bangladesh. It is therefore not very hard to understand how the vast areas of forests have been razed to the ground in the last decades due to logging and cultivation and to use the forest land for other purposes. Adoption of wrong policies by the government and corruption by foresters have nearly eaten away most of the natural forests. In addition, rubber monoculture, commercial fuel-wood plantations, grazing, urbanisation, and expanding agriculture have drastically reduced Bangladesh's natural forest. On top of habitat loss, the biodiversity of the natural forest is suffering from illegal poaching. Over the years, the wildlife of Bangladesh has been facing very dire situations out of 140 mammals species around 110 are endangered. The department of forest only manages 1.52 million hectares (around 10 percent of the total land mass). The rest of the forests are titled as un-classed forest .73 million hectares and village forest .27 million hectares. Currently there are 15 national parks and 13 wildlife sanctuaries and five protected areas in the country. The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove forest in the world. The area of Sundarbans has been recognised globally for its importance as a reservoir of biodiversity. This mangrove supports a unique assemblage of flora and fauna, including exotic animals like the Royal Bengal Tiger, Estuarine Crocodile and the Ganges River Dolphin. The Sundari tree, for which the sundarban is named, is a endemic species of this forest. The government is currently amending the Wildlife (preservation) order 1973. The primary analysis of draft of the Wildlife Act (Amendment) 2010 shows it will allow the government to permit any kind of activities in the buffer zone of the forests. Another criticism is, the draft encourages to plant trees in the forest rather than protecting the natural forests and biodiversity, even in the Sundarbans. Arsenic Contamination Waterborne diseases such as cholera are a serious threat to public health in Bangladesh. Until the 1970s, many of Bangladesh's people became sick from drinking polluted water drawn from surface rivers. Aid agencies such as the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) built shallow wells throughout the country to help provide a safe source of drinking water to Bangladesh's poor. In the 1990s, however, it was discovered that many of these wells were contaminated by arsenic, a poison that occurs naturally in Bangladesh's alluvial soils. The World Bank estimates that 25 percent of the country's four million wells may be contaminated by arsenic. In 1998 the World Bank granted Bangladesh a $32.4 million credit to identify contaminated wells and develop alternative sources of safe drinking water. Air Pollution According to the Department of Environment (DoE), the density of airborne particulate matter (PM) reaches 463 micrograms per cubic meter (mcm) in the city during December-March period - the highest level in the world. Mexico City and Mumbai follow Dhaka with 383 and 360 mcm respectively. An estimated 15,000 premature deaths, as well as several million cases of pulmonary, respiratory and neurological illness are attributed to poor air quality in Dhaka, according to the Air Quality Management Project (AQMP), funded by the government and the World Bank. In recent days campaigns have been carried out by the print and electronic media such as environmental issues picked up by The Daily Star have spurred widespread public concern and promoting reaction at the highest political levels. In recent years, the government has taken some important steps towards protection of the environment, environmentally sound use of natural resources and pollution control. To take prompt legal action against environmental pollution, successive governments have taken many steps including formulating many laws to protect the forest and environment of Bangladesh. The environmentalists pursued the government to formulate Bangladesh Environment (Preservation) Rules 1997 the umbrella law under which many new rules were formulated. Later the government made the ‘Open Space and Wetland Protection Law 2000’. But in most of the cases the laws remain in the book. However, the government has signed many international treaties and convention and also introduced many new laws in the last two decades when the country's environmental components were severely damaged. The government also has set up the Bangladesh Environment Court to take quick action against environment polluters. But that has not helped to curb the unabated degradation of the environment. At the same time, Bangladesh has seen many success stories in the environmental sectors. Thanks to the media campaign in the last two decades or so, the public has become more aware about the environment. The present Government has proved itself as an environment friendly one through undertaking various programmes toward upholding and conserving the environment. The first success story was obviously banning of use, production and marketing of polyethylene shopping bags in 2002. People from all walks of life have given overwhelming support to implement this ground breaking step. The then government also took step to control vehicular air pollution by banning on plying of two strokes three wheelers in Dhaka City from January 2003. Besides all these, successive governments considered some other important issues like wetland conservation, electricity generation and manure production from municipal wastes, making rivers pollution free, making ship breaking activities environment friendly, etc. While some of these strategies have been initiated, most of them have not seen the light of day. The present government also has taken many steps to protect the environment especially to save the rivers. The government has taken a massive project to dredge all the major rivers in the country as well as massive afforestration project across the country. But still the country is waiting to see the results of these initiatives. The writer is Deputy Chief Reporter of The Daily Star. Lifestyle Two decades Technology and capitalistic values reshape Bangladeshi lifestyles Raffat Binte Rashid

The last two decades have been witness to changes both sweeping and dramatic in Bangladesh. Be they in terms of subscribing to the technological revolution, of urbanising and globalising our cities and our lives or of giving in to the fast-paced lifestyles that have begun to define our ways. These transitions have changed life as we knew it before, and a sizeable sect of Bangladeshis today are no less cosmopolitan in shape or form than dwellers of most major cities in the world. Tech Savvy Me A decade later, as they turned into adults they saw their first computer, the advent of cable television and the jargon of globalisation gaining popularity but barely making sense as yet. The nineties beckoned a day and age where big, fat, almost ugly mobile sets were the epitome of tech savvy-ness.

However, the turn of the century ushered in another decade where technology took a giant leap that unleashed great opportunities and pushed mankind to the pinnacle of his potential. The nineties and the noughties were all about dexterity, expertise, equipment and technological know how. These drastic changes however, implied high levels of redundancy by default; the floppy disk of the nineties, for example, is now an auction piece and even school children are rarely found unarmed with pen drives. Smart phones, Ipods, portable hard drives and laptops have fast replaced the likes of walkmans and discmans which were all the rage not so long ago, when they seemed to be the zenith of technological advancement. VCRs (Video Cassette Recorder) and two-in-ones have suffered similar fates, as have audio cassettes and VHS (Video Home System) cassettes, which were ousted first by VCDs and audio CDs, then by DVDs and MP3 players. It is sometimes hard to keep up with this rampage; even DVDs are becoming yesterday’s news now with the advent of amazingly high-quality Blue Ray discs. In 2010, these had become all relics of bygone days, collecting dust and cobwebs in our drawers; to be smiled at when stumbled upon, but no longer used. Land phones used to be the lifelines of the eighties. If a house had a phone connection, it automatically became a public booth for neighbours known and unknown, including the grocer downstairs. Just to get a connection one had to wait months, even years in front of TnT offices. By the nineties, this has become a mundane affair and cell phones were what the rich showed off as their new gizmos. By the turn of the century, cell phones were no longer restricted to the affluent and today even farmers in villages have mobile phones that not only keep them connected to loved ones but also increase their business opportunities and day labourers have earphones plugged in to listen to their favourite FM stations. This can also be called ‘The Age of Integration’ as mobile phones now triple as high-resolution cameras, MP3 players, and browsers. Aside from mobile phones, another mammoth influence on our lifestyles has been the Internet. No information is unavailable and no person unreachable. With services such as train tickets available via cell phones, the device is now a basic necessity and not the luxury that it was considered even a decade ago.

The heightened use of the Internet has meant that we need never be out of touch. If the morning paper does not make it to one's doorstep, he or she can always log on to the net and read not only the paper that he or she subscribes to, but also news from virtually anywhere in the world. Sites like Facebook and Twitter ensure that you can share every little detail of your life with friends and family, regardless of where they might be in the world. Instant messaging services provide the introvert with a platform to interact that doesn't impose the same intimidating social skills for face to face interaction. The much romanticised practice of keeping a journal has lost favour to blogging and preparing presentations online, reading e-books or listening to music on Youtube are part and parcel of generation . But as always, there is a flipside to the coin, and the caveat of this inundation of technology is that we are becoming more and more cocooned in our own lives. Often, we may know the tiniest details of the lives of acquaintances living halfway across the globe, but might know nothing of the travails of our next-door neighbours. In the face of the irresistible march of technology, we as individuals have become more isolated than ever before. The Middle Class Urbanite

An increase in purchasing power, greater exposure to world trends through electronic media and rapid urbanisation have created influences on lifestyle beyond the control of the middle class urbanite. By the mid-eighties, someone awoke the sleeping giant - consumerism – and there was no stopping it. Dhaka grew into this metropolis of trendy shopping malls, happening cafes and skyscrapers. Dhaka's cityscape also started to change drastically from the early nineties, mainly due to the centralised nature of the Bangladesh economy. An increasing number of people started developing homes and living in the suburbs and this was complemented by the rise of a number of different types of motor vehicles. In this day and age, couples living in their posh 3000 plus square feet flats SMS friends to come over for after-dinner drinks or coffee. The change is obvious and fascinating. The way our living standards, our priorities in life, and our responsibilities, even our tastes and preferences have changed and adapted to new trends is worth mentioning. With so much happening in the lives of the middle class, consumerism has taken a different meaning. A thriving market reflects a thriving middle-class, because their buying capacities determine the success of an economy. The late eighties and nineties with their open markets, aggressive advertising and cable television added a new dimension to our lives. Over the last two decades, what we saw on TV or read in magazines or even heard from friends is what we wanted to look like or live like. Exposure to other cultures by travelling or migrating has allowed us to adopt many new values and preferences influenced by the West. Today, in most middle class homes both the husband and wife earn. Women are working in offices and this is no scattered incident like in the eighties when working meant only teaching in schools. With her financial independence, a woman of this era lavishly spends on grooming herself, on furnishing her home, on educating her children and or on entertaining her friends.

The busy noughties women paved the way to a lifestyle change among many ultra poor. A homeless woman with two kids from the village who came to the city for a better life almost realised her dream by working for today’s office-going woman. The latter now depends entirely on her house help to complete the day’s chores and run outside errands like picking up children from school. Basically the lady of the house now depends heavily on her service people to run her house for her. This dependence comes with a hefty price tag though; the village woman who came to her house to work now gets a health benefit, a bank savings scheme, can afford a TV with cable connection and most importantly has the opportunity to educate her children. Another new phenomenon is that of shopping as a means of entertainment. Due, perhaps to limited budgets, and also the lack of facilities, this was unheard of in the seventies. Eating out was also a rare pleasure. Today, a major form of entertainment is shopping extensively or dining at trendy restaurants offering cuisine from different cultures. The shopping scene has also been largely influenced by the cell phone revolution. The woman of the new millennium does her monthly bazaar over the phone. Fishmongers, vegetable vendors and fruit-sellers are all equipped with mobiles these days and one phone call is enough to have fish bought, cleaned and delivered to the buyer’s doorstep. Such drastic changes have been experienced across all walks of life. From wearing bell bottoms and elephant-ear collar shirts to baggies, to discos to trendy fusion; from receiving love letters in blue envelopes to a hundred SMSes a day saying 'I love you', Bangladeshi urbanites have indeed come a long way. The Chic Factor How do you identify a man or a woman of the noughties? By the gadgets they are plugged in to, the cars they drive, the brands they wear and where they hang out? Couples today are constantly on the move; if careers are their first priority then children’s welfare and taking care of elderly parents jointly take up the second spot. There is an unseen competition where one couple must outdo the other in their social circle in terms of which school or university the child goes to or where the family goes for summer holidays. These subtle things have clouded social rankings and those involved do everything possible to keep up with the increasingly frenzied pace of the city. However, with Dhaka’s booming corporate culture, it is not hard to maintain this status for a couple whose joint annual income comes close to four million. Moreover with extremely aggressive marketing strategies and a thriving market economy, dreams are now easier to realise. Banks are prepared to hand out loans for higher education, weddings, travel, car loans and even loans to buy basic household electronics besides the usual house building and business purpose loans; if you have the financial strength to repay your debt, you simply grab the opportunity. Dhakaites have money now and they spend thousands on just grooming alone, both men and women now regularly go for spa treatments or massages, manicures and facials. They have learned to entertain in style where fine dining is a regular weekend affair. The downside of this consumer-driven society is the high cost of living, an ultra-capitalistic attitude, degradation of good morals and a money-driven populace. Living in Style Although those beautiful houses and all others like them have given way to modern day apartments, their interiors left a profound mark on ‘generation next’ for which we see such well planned interiors today. Today’s architecture and interior decor all have roots tied firmly to our rich past. Those old aristocratic houses in Purana Paltan, Wari, Shegun Bagicha and Dhanmondi instilled the desire inside all of us to live grandly within whatever small or big apartments we build for ourselves today. In fact, to accommodate our ever-booming cosmopolitan city, pocket houses or apartment buildings became mandatory. The grand yesteryear houses were adequate for the big families then, but with the gradual addition of second and third generations, those duplex mansions became claustrophobic. The only way out was vertical expansion leading to current multi-storeyed skyline. It was a much-needed development. However, good living and aesthetics have not taken the back seat for such expansion. Traditions have definitely worked as reference points while planning. The arches, the khorkori windows, the long verandahs, ventilation systems, the importance of natural light, storerooms, attics or chille khotas were all given a new lease and re-modelled. As is the case with every other all-encompassing, all-altering change, these modifications in the lifestyles of Bangladeshis over the last 20 years have their pros just as well as their cons. Over the course of time, as we mature as a nation and slip more firmly into the definitions and dimensions of ‘urban’ and ‘global’, we can but hope that our balance will tip more heavily towards the pros rather than the cons. The writer is Editor, Lifestyle, The Daily Star. Trends Trends that changed our lives 1. Mobile Phones

2. Internet and Computing

3. Women At Work: Women in the Army

4. Satellite Channel

5. CNG

6. Real Estate Boom

7. Bangla Rock

8. FM Radio

9. MediaBoom

10. Pharmaceutical

Perspective Bangladesh at the Crossroads Tahmima Anam

This article is being reprinted with permission. It appeared first in the Financial Times (FT) Magazine on March 18 2011. It is winter and Dhaka is full of lights. Shaheed Minar, the memorial commemorating the Language Movement that led to the independence of Bangladesh, glows a bright orange. In the posh neighbourhoods of Gulshan and Baridhara, entire apartment buildings are illuminated to celebrate winter weddings, but these are overshadowed by the bright lights of new shopping malls. This is the city into which I have just landed – lit up, hopeful and humming with electricity. I am a sheeter pakhi – a bird who has flown east for the winter. Every year I travel home to visit my family and reconnect with Bangladesh. There's something about this country that inspires a deep longing, and whenever I am pulled back, I come home to take stock. This year, on Bangladesh's 40th anniversary, I ponder the great changes that have occurred here, ponder the brightness and vitality of a country that no one expected would succeed. But succeed it has. Its dramatic transformations – imperfect, yet to be fully realised – are testament to the resilience of its people, and to the great power of democracy that is hard-won and home-grown.

As always happens when I land in Dhaka, I am immediately struck by the sense that something exciting is about to happen. In early February, the city is abuzz with anticipation because the ICC Cricket World Cup will kick off at the Mirpur Stadium in just a few weeks. People are scrambling for tickets. Municipal elections mean that every available intersection and telephone pole and exposed brick wall is festooned with political posters and slogans. This year the agents of change seem to have raised their voices, and I realise something has shifted in the tone of the country. The stakes are higher, people are restless, poised for even greater transformation. In the meantime, the things that are difficult – that make you avert your eyes – are as apparent as ever. The city is full to bursting, and everywhere there are signs that the changes have not reached everyone: not the children picking through rubbish heaps on the side of the road, not the women who cook dinner over roadside ditches, thin sheets of blue plastic the only thing between them and the bitter winter evenings. Bangladesh was born out of a brutal war of secession from Pakistan in 1971. During those nine months, the Pakistani army conducted a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing, killing up to three million civilians and forcing as many as 10 million into exile in neighbouring India. Two days before the war ended, knowing they were on the brink of defeat, the retreating army assassinated hundreds of academics, physicians, artists and journalists in order to give the yet-to-be-born country as little chance of surviving as possible. The new prime minister, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was welcomed by a population on the brink of famine. These are the factors that led Henry Kissinger to peer into the newborn country's cot and declare it a basket case. Since independence, instability has pervaded the political climate. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was killed in 1975, along with 19 others, including 16 members of his family. Less than a decade later, his successor, General Zia, was also assassinated. Coups and counter-coups were followed by the long military rule of Hossain Muhammad Ershad. And yet, somewhere along the way, the tide turned for Bangladesh. In 1990, a popular movement for democracy, not unlike those we've seen recently in Tunisia and Egypt, ousted Ershad's nine-year-old dictatorship. Since then, aside from a brief period of army-backed civilian rule, power has been handed back and forth peacefully between Mujibur's party, the Awami League (led by his daughter, Sheikh Hasina Wajed) and General Zia's Bangladesh Nationalist party (led by his wife, Khaleda Zia), in a series of increasingly transparent national elections.

Now, four decades into nationhood, there are many things to celebrate in Bangladesh. The economy has enjoyed 5-6 per cent growth for the past three years. The ready-made garments industry is thriving, surpassed globally only by China and Turkey. And last October, Bangladesh was given an award for the strides it has made towards reaching the UN millennium goals in health (notably, in reducing child mortality rates), education and women's rights. Perhaps even more importantly, there are strong movements to restore Bangladesh to its secular roots. Last year, the High Court and Supreme Courts banned fatwas and legally returned Bangladesh to its founding status as a secular republic. Later this year, a war crimes tribunal will begin trying the men who collaborated with the Pakistani army during the Bangladesh genocide. For the past 40 years, politicians have been bragging about their past as war criminals, daring any government to put them on trial. If the tribunal is a success, this culture of impunity may finally come to an end. This is not to say that all is well. Bangladesh has a well-documented history of corruption at all levels of political and civil administration. Opposition forces are often brutally suppressed, and there has been a systematic abandonment of ethnic and religious minorities. Every day, troubling stories emerge about the excesses of the Rapid Action Battalion, the paramilitary police in charge of law and order and anti-terrorism.