| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 21 | June 03, 2011 | |

|

|

Perceptions The Meaning of Seeing Things Andrew Eagle It's quite a thing to wear glasses: a beacon for bullies. Schoolyard taunts from immature minds are unimpressed by what was sometimes called 'facial furniture.' It must be quite a challenge to self-esteem. I couldn't say with certainty though, as I'm blessed with twenty-twenty vision. Years ago, another tea shop moment in By-the-Big-Bridge, Hatiya; late afternoon was giving in to early evening. In such moments there's little to do but gaze at the strip of road that gives way to the little bridge over the canal and to ponder the merits of breathing-away an afternoon in such a fashion. Situ was there, similarly awaiting some conversational front to stir the place. That's when the pair of glasses arrived. They belonged to a university student, hair carefully combed, shirt tucked in; neat, respectable and typical. 'Those glasses aren't real,' Situ said. 'What?' I asked, enjoying the unexpectedness of the statement. 'They have plain glass,' he said, 'young people wear them to look smart.'

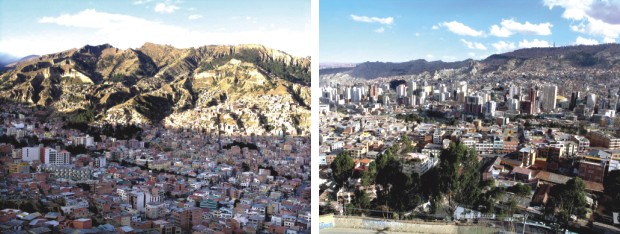

I suppose it's not surprising. People pump Botox into their faces for looks, but if it was fashion why not choose sunglasses like everybody else? Situ was jesting, surely. I had to know. 'Excuse me?' I said to the guy, 'I need to borrow your glasses.' He took them off in that nonchalant way villagers do; in the village things generally run their course unchallenged, everybody wanting to see, without a hint of prediction or inquiry, what will happen next. Sure enough they were fitted with plain glass. The trouble with South America is it's a long way from Hatiya. I used to feel that when I lived there; why I'd made my English class of professional adults study Tagore, so at least we could talk about Bengal. You won't find him on any syllabus. The Bolivian capital La Paz is an unlikely city, clawed out of an Andean valley 3600 metres above sea level. Its sunset is of shadows rather than light, as the rim of the high plateau sends a gradual line of darkness across the bowl of the city. The temperature drops a few degrees at the shadow-line; noticeable enough to want to stay sun-side. As late afternoon was giving way to early evening my student Bernie called and said to meet her by the witches' market the following day. When I arrived she said she wanted to buy me a farewell gift. I was set to start a new teaching job in Nicaragua.

In that part of town souvenir shops competed for space with those selling the supplies of ritual offerings: potions, twigs, coca leaves and dried llama foetuses, used by local priests called yatiris, for sacrifice to Pachamama, the mother-spirit of the Andes. Pre-Columbian beliefs live on. She found a traditional coat, in black and red with colourful indigenous designs across its chest and sleeves It must've been because I was leaving La Paz, a city that had become familiar and full of friends, but as I put on that coat I remembered Hatiya, and funnily enough those glasses. Bernie led me down past the grandeur of San Francisco Church and across the square. In a more or less unbroken row were the stalls selling frames, which came with plain glass in them on purchase. I'd told Bernie the story; we'd decided it'd be amusing if I wore plain-glass glasses to my farewell party. I'd be able to take 'glass-wearing' photos to send Situ. There was the usual bargaining: we'd laughed as they offered discounts at the optometrist's to have the prescription lenses fitted. I settled on a black steel-rimmed pair Bernie said suited. The following afternoon, the last of several farewells since Bolivians were rather reluctant about departures, I sat at a touchingly long table on the lawn of a restaurant in the fashionable Zona Sur district. Another student, a doctor called Fernando was there, as we waited for the guests, for Bolivian time to reach us. Bolivian time is somewhat later than Bangladeshi time. I played with my glasses. As a prop they were great. With Fernando I practised the various postures: the pensive glasses hanging by one handle from the mouth; the confrontational looking over the rim whilst addressing people; the holding them in your hand for emphasis like a pointer; all the opportunities people who really wear glasses have. I asked if they'd work in the classroom and rehearsed 'do your homework' with glasses on and off, considering which was more compelling. 'If you wear those people won't talk to you,' he joked. 'Why not?' 'Because you look so intelligent they'll be scared they might say something stupid!' 'I didn't know you wore glasses?' everybody said. They'd known me for more than a year and never seen glasses before, and here's an interesting thing: people are so unwilling to trust what they know. 'Try them,' I tempted. One by one they put the things on. 'Do you need them only for reading?' 'The prescription is very minimal,' they said, being too polite to challenge outright. There was only one student with enough courage to say it: 'these are not real!' Through lunch in the afternoon sun they heard of a rustic tea shop in Hatiya and the glasses became a source of mirth. For me it was especially nice, as in some way the village at the flatland mouth of the Meghna sat at the table too, to share the high-Andean enjoyment. Glasses are quite annoying. I understand why people take them off, how easily they are lost. My little experiment taught me that, especially in Nicaragua. I'd settled into one of those gorgeous colonial villas, Spanish-style, that make up the city of Granada. It belonged to an ageing couple who rented rooms to travellers, mostly Americans. The very Catholic household we shared with two kindly servants, a parrot, a cat, and two turtles in a bucket. There were many guests, but it was an American, Christine, I'd befriended. She was impressive; a literature graduate who wore glasses herself, and all kudos to her, the moment she tried mine she declared them a fraud. I told the story of a Hatiyan tea shop and a La Paz restaurant. There are photos of me around Granada wearing glasses. The house guest from Florida who'd accompanied me thought it odd I only needed glasses for photos. I told the story. When she saw the pictures later she said, 'you know, you really do look better in glasses.' I loaded the Granada glasses photos onto the internet, typed the Dhaka address and pressed 'send'. It happened many times: my Nicaraguan mother or one of the servants had come across my glasses lying about. As caring as they were, they'd put them aside, warning as clearly as they could in Spanish, 'you should look after your glasses; you'll lose them.' There was only Christine to provide the knowing, bemused look. Those glasses are on a shelf somewhere in the Sydney house, a pair of innocent-looking respectable spectacles that cannot improve anybody's vision but mine; for just to hold them is to conjoin the unwinding of a lazy Hatiyan afternoon, the communion of a La Paz farewell and a home in Granada with a parrot, a cat and two turtles in a bucket. In Hatiya I don't see that guy wearing the plain-glass glasses anymore. Fashions have moved on. In Kolkata when last I was there people wore those jeans with random pleats in their legs to look perpetually unironed. Now why would anyone wear jeans like that?

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||