| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 13| March 30, 2012 | |

|

|

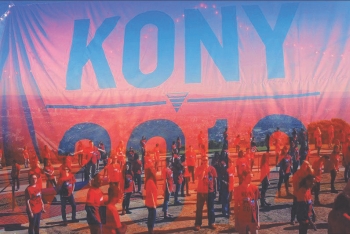

Perceptions The Kony Virus Adnan R Amin

In February 20, 2012, the San Diego based not-for-profit organisation Invisible Children Inc. uploaded its superbly-produced, uplifting 30-minute documentary 'Kony 2012'. Their goal was to get 500,000 views and eventually, get the Ugandan guerrilla leader Joseph Kony arrested by 2012. Six days later, it reached an aggregate 100 million views – faster than other pop-culture phenomena like Susan Boyle (9 days) or Rebecca Black (45 days). Kony 2012 is now the most rapidly disseminated human rights video ever. Long story short, in 2003, three filmmakers including Kony 2012 director Jason Russell travelled to Africa to document the Darfur genocide. There they learned of the rebel LRA's war against the government, decided to do something and formed the non-profit organisation, Invisible Children. The Kony video, directed and narrated by Jason Russell, features clips of his time spent in Africa and footage of Russell's conversations with his son. The video details Kony's history followed by instructions to spread the video and donate to the organisation. The rest, is far from history. The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) is a Ugandan guerilla group inspired by a breed of Christian Fundamentalism and aims to establish a theocratic state based on the Ten Commandments. The LRA, declared a terrorist group in 2008, has long been accused of abduction of children who have been used as soldiers and sex slaves. Its leader Joseph Kony is a shaman of a warlord, a self-proclaimed Spokesperson of God, a husband to 88 women and a war criminal of the worst kind. He remains wanted by the ICC and hunted by US Special Forces in four Central African countries. Kony 2012 is not just a video but an online vigilant campaign with a 'join the revolution' appeal, capitalising on viral media content. It set Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, blogs, news sites, YouTube and Vimeo afire with the hottest new supervillain. The hashtags #kony2012 and #stopkony became globally trending terms on Twitter, some ranking higher than the new iPad! In addition, virtual stores were selling posters, campaign buttons, posters, bracelets, stickers and other merchandise to help people organise demonstrations and voice their support for Invisible Children's viral campaign. The promotional 'Cover the Night' event entails virally spreading Kony 2012-related media in major cities from sundown on April 20th, 2012. All major news outlets including CNN, BBC, Reuters, Huffington Post, The Guardian have covered the Kony story till date. Invisible Children, which is an advocacy organisation, also (albeit adroitly) targeted celebrity 'culture makers' and as Kony 2012 went viral, celebrities like Justin Beiber, Bill Gates, Kim Kardashian, Nicki Minaj, Taylor Swift, Rihanna and Emma Stone were retweeting and endorsing the campaign. Oprah Winfrey's (9.7 million Twitter followers) endorsement sent hits skyward. The White House press secretary announced that President Obama (who appears to support the movement in the film) had praised the people who responded to this 'unique crisis of conscience' and pledged to continue the disarmament of the LRA. *** Of late the Kony campaign has fallen victim to the Icarus Syndrome - its overwhelming success being its biggest problem. Fame has brought scrutiny and eventually, helped uncover certain inconvenient facts. The LRA, it seems, is a problem of a bygone era – reaching its height during the 1990s. Remnants of Kony and LRA were finally pushed out of Uganda in 2006 and have now become quite insignificant. The 'Nodding Disease' is a much more potent threat to Ugandan children. The LRA numbers are estimated in the hundreds and not the 30,000 as the documentary suggests. The content and tone, which doesn't consider Ugandan audiences, has been dubbed insensitive, frivolous and misleading. Chris Blattman, political scientist at Yale, stated Invisible Children's programme 'hints uncomfortably of the White Man's Burden... the saviour attitude'. Another Ugandan journalist asks what justifies such a massive production campaign and lucrative donation drive? Invisible Children expertly 'commodifies white man's burden on the African continent: Buy a bracelet, soothe some guilt'. Ugandan Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi got on YouTube to declare 'the Government of Uganda is acutely aware of the grievous damage caused by Joseph Kony and the Lord's Resistance Army. We do not need a slick video on YouTube for us to take notice.' Mbabazi has also taken to Twitter to invite the targeted celebrities to come to Uganda and see the country for themselves. “I just hope it sows the seeds of a new generation with a real interest in how Africa and its people can progress, in understanding why the world is like it is, not 'lots of Africans just kidnap and kill each other, but white people can help.” Duncan Green, Head of Research at Oxfam GB Invisible Children's rather irresponsible, albeit supercharged, campaign has drawn a lot of flak. Their fundraising attempts have attracted attention to their financial practices. According to their own financials, Invisible Children spends a whopping 70% of its funds on production of films, overseas travel and staff salaries – the rest going to direct services. The organisation has defended its expenditure saying it's not a typical aid-agency – but an advocacy firm. At the height of the controversy, Jedidiah Jenkins, Director of Idea Generation at Invisible Children, suggested that their film had been developed for school children – and shouldn't have been subjected to the scrutiny of The Guardian. Recently, director of the film Jason Russell was found running about in an indecent state, arrested and admitted to an institution. His family claimed that widespread criticism had brought on the episode. *** We need not wait till 20th April to realise the campaign has gone viral. That Kony 2012 is unleashing so many exuberant activists, albeit armed with very few facts, leads one to wonder the secrets of this success. Which is just too bad because this campaign has the makings of a truly transformational development-communication experiment. Still, their strategies may be replicated in development and health communications as social-media gains momentum in Bangladesh. Social-media movements like those against BSF Brutality and Tipaimukh Dam can learn from Invisible Children. Leaders can learn how to channel youthful energy to worthy causes. They seem to have got the basics right. The easiest answer may be that Kony 2012 engenders the most timeless, most tried and tested recipe in communications or story-telling: a villain, a problem, a solution and a hero. Invisible Children first created their own story – a bunch of passionate development workers with a dream. They mainly targeted young, white students – change-maker types-playing on the cultural 'white savior' complex. The distinction between dichotomies of 'us vs. them', 'young vs. old', 'propaganda vs. activism' helps the audience identify with the cause. It may not be Kony that drives them – but rather a need to belong. Youth cutting across geographic boundaries and ideology by way of social-networking is a potent motivational force too. The audience, young and probably first-time involved in anything that smells like activism, is ripe. Green of Oxfam points out that '(Kony 2012) adds dollops of Hollywood feelgood schmaltz to that equation – 'we can do it!' 'Hey, they're just like us!' 'Feel the love!' 'Kids are cute!'.' They are, in fact, speaking the language of the youth. And explaining as though to a child (the film-maker's son Gavin) helps (over)simplify the issues too. The setting is a distant Uganda, a land of perceived misery and murder that can never graduate without the white man's development work. While condescending, it actually appeals to a genuine sense of philanthropy in idealistic, young people. At a time ripe for activism, Invisible Children started out with a specific villain: Kony …not a faceless affliction like poverty, war or AIDS. His crime is against children – the global charity-magnet. The message is clear and concise: stop Kony. How do you do this? Simple: make Kony famous. In this ingenuous 'you can run, but you can't hide' assault, audiences are not passive viewers – but active campaigners – heroes, who are to stop Kony. There are very specific, actionable instructions in achieving this: share video, buy bracelet, give money. The goal is clear: get Kony arrested; the strategy is simple: make Kony famous; the deadline is set: end of 2012. That's more than enough direction. And with his sort of clicktivism, people can engage in without hampering their everyday lives. And lastly, the optimised mix of virtual networks, social media and merchandising helps access and motivate the specific audience and greatly expedites the single success factor for the campaign: reach. That Kony 2012 has gone viral like it has - is not coincidence, its elementary.

|

||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |