| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 26| June 29, 2012 | |

|

|

A Roman Column BURIED HISTORY Neeman Sobhan

The waning sun of late afternoon filters through the rows of pines lining the long narrow road, casting shadows. It's past the museum's closing hour. Not a soul around, except our car parked in a patch of shade. My husband at the wheels urges me to take our visitor through one of the gaps at the edge of the fields where steps carved into the earth and covered with weeds and wild flowers take you down to what looks like a dug-out mud road surrounded by grassy mounds and gaping cave-like openings in the rocks and hillocks. We stand looking at what seems like an excavated Pompei street. But glancing at the dark doorways, shadowy windows and holes like empty eye sockets, we can feel that these were never the habitations of the living. The bland, departing sun flits like a lost butterfly among the scattered oleander bushes; the wind soughs in the pine branches like a restless ocean, the sigh echoing and multiplying in the woods in the distance, in the flushing of bird wings, and the fricative resonance of crickets. Something about the quietness before us is disquieting. The emptiness is filled with a heaviness. And then the silence is broken by strange screeching in the trees. It's like and not like peacocks. It's the cry of angry birds, a threatening noise. We beat a hasty retreat and climb back into the car. My husband laughs at us. “What, no one at home? Had enough of visiting your dead Etruscan friends?”

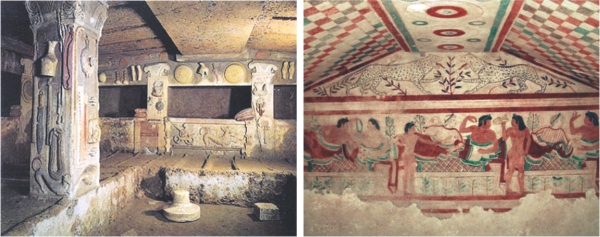

I tell him it is just the hour of the day. I have been to this ghost city before, in the blazing clean sunlight of mid-morning. It was a fascinating walk through the burial grounds of the mysterious Etruscans, who came from nowhere, and disappeared leaving no traces of their thriving civilisation except in their elaborate tombs dug inside the well planned streets and 'neighbourhoods' of their City of the Dead. As we drive away, I am sorry that we have given our visitor an incomplete experience of this historical graveyard: eerie but not evocative in a historical sense. But she is herself avid about Italian history and promises herself a revisit to Cerveteri's famous Necropolis. Cerveteri (ancient name Caere) is an Etruscan town to the north-east of Rome, famous for its Etruscan burial grounds, tombs, excavated sarcophagi, fresco, pottery and other relics. It's the largest ancient necropolis in the Mediterranean area, and along with the necropolis in Tarquinia, it has been declared by UNESCO a World heritage Site. The tombs, often housed in characteristic grassy mounds, cover an area of 400 ha, of which only 10 ha can be visited. These ancient tombs, date from the 9th century BC. The most recent ones, dating from the 3rd century BC are of two types: the mounds and the "dice", or simple square tombs built in long rows, like houses, along "roads".

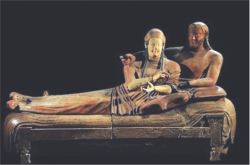

The mounds are circular structures built in tuff, a volcanic rock, and the interiors are carved from the living rock revealing rooms as if in an Etruscan home. Most of the tombs are constructed like houses, including a corridor, a central hall and several rooms. Modern knowledge of Etruscan daily life largely derives from the numerous decorative details and finds from such tombs. The most famous of these mounds is the so-called Tomba dei Rilievi (Tomb of the Reliefs, 3rd century BC), provided with an exceptional series of frescoes, bas-reliefs and sculptures portraying a large series of contemporary life tools. Of the graves thus far uncovered, none is finer than this tomb of the Matuna family. Articles such as utensils and even house pets were painted in stucco relief. Presumably, these paintings were representations of items that the dead family would need in the world beyond. All these have helped historians reconstruct the life of the Etruscans, which would be an impossible task given that these people left no written history. A large number of finds excavated at Cerveteri are in Rome's National Etruscan Museum (Villa Giulia), while others are in the Vatican Museum, and other museums around the world. Some relics and pottery are also kept in the Archaeological Museum at Cerveteri itself.

|

||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |

|||||||||