| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 41| October 19, 2012 | |

|

|

Cover Story

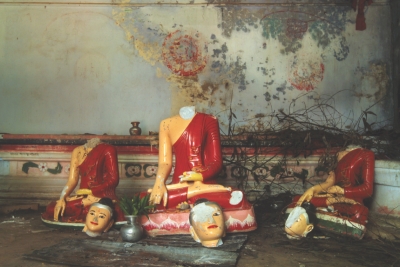

THE FLAMES MAY BE LONG GONE... More than two weeks have passed since the orchestrated attacks on the Buddhist community in Ramu, Teknaf, Patiya and Ukhiya. Although over 260 people have been arrested on different charges, and all three major political parties have been implicated, the masterminds of the attack are yet to be identified. Meanwhile, the local Buddhists continue to live in insecurity, fear and apprehension. Sushmita S Preetha (back from Ramu) No amount of newspaper reports, op-eds, news video clips or Facebook images prepare you for the intensity and magnitude of the destruction that took place in Ramu, Ukhiya, Teknaf and Patiya on September 29 and 30. The places look vaguely familiar as you walk through the debris, ashes, broken statues and burnt puthis (religious scrolls) – perhaps you remember the reclining Buddha from a childhood visit to Cox's Bazaar. Or perhaps it is the images you have seen of the wreckage on television channels and newspapers as they rushed in to provide raw footage of the aftermath that make you feel as if you've been here before. But there is nothing familiar about the overwhelming hate and cruelty that exudes from the remnants of the temples, monasteries and shima bihars – at least not for those who have never seen a Gujarat massacre or a Babri mosque demolition. How could they, you ask time and again, as you stroll through each temple and view the intricate artwork that is now destroyed, the statues that now lie beheaded, the ancient texts that are now disintegrated remains. They are buried amid tin sheds, bricks, wooden furniture, pillars and fallen trees, not really waiting to be rescued or replaced; they are there more as reminders of the unforgiving atrocity that took place in the holy places of worship.

If you are a Buddhist standing amongst the ruins of your past and present, the pain you experience must surely be more powerful than the outrage we, as the majority, no matter how secular or progressive, feel as we write our editorials, organise press conferences or hold rallies to protest the grave incidents. “Are you a Barua (a Buddhist surname), ma?” asks an elderly woman, wrapped in a plain white cotton saree as if in mourning, her voice betraying her otherwise composed demeanour, “Then how would you possibly know how I feel right now? How can I express the betrayal, the insecurity and the pain with just words?” She is no longer a local, she says; she left Ramu thirty-five years ago when her husband moved to a different city in a far-off land. Now she has travelled a long way, by herself, to see her wrecked hometown, even though her health does not really allow her to move around anymore. “I couldn't sit at home as I saw image after image of the destruction. I had to pay my homage. Besides, what if they destroy the little that is left?”

Fear and insecurity are evident in the faces and voices of the locals, too. “We don't want money; we want a guarantee from the government that nothing like this will happen again, we want assurance that the Buddhist community can survive in Bangladesh,” says Polash Barua (not his real name), whose house, overlooking the Laal Ching in Ramu, was attacked on the night of the 29th. Their apprehension is also apparent in their unwillingness to divulge their own names as they recount the horrors of that night or give particulars about the perpetrators. When asked what or whom they are afraid of, they shrug as if to say, “Isn't it obvious?” Some clarify that they have received threats on the phone and in person; others say they don't want to be identified and feel alienated by their Muslim neighbours and colleagues. Villagers in Teknaf reveal that local goons walk around saying, “How long will the army protect you? Make too much noise and we will make sure all the Baruas' heads are cut off.” Whom will they believe, the government and well-wishers who insist that justice will prevail, or the malicious and powerful henchmen who so deliberately ruined everything that they hold dear? Two weeks after the fateful night, Ramu still looks like a scarred battlefield. The rubble, ruins and ashes are everywhere in the premises of the holy sites. Tents for the army stand erect amidst the debris, and many of the burnt and broken houses remain as they did weeks ago. They are crime sites, after all, and should not be touched or tampered with. But there's more to it than just practicality; it's almost as if the locals want you to see, really see, the extent of the rampage; they want to share their pain and their outrage with the world; they don't want to fix things because they don't know how. Unlike an abandoned battlefield, however, Ramu is bustling with activity, people and noise. In some odd way, it seems more alive in its bereavement than it did when it was a regular tourist site. There are people clicking away with their cameras, conducting interviews, holding protests, giving fiery speeches, distributing relief. There's something positive to be said, of course, about all the individuals and groups travelling from far and wide to show their solidarity, conducting independent investigations and providing help. One hopes, however, that in our haste to show our progressiveness, we don't end up romanticising the violence and the experiences of the local Buddhist community, that we maintain a critical outlook on what happened as we hurry to give rice and clothes or take pictures in front of burnt temples to upload on Facebook.

The events of the night of the September 29 and 30 are now well-documented. We know that, infuriated over a derogatory image of Islam in Uttam Barua's Facebook account, mobs gathered in different parts of Ramu on September 29 to protest the action. What began as meetings and rallies turned into a violent riot late in the evening, with thousands of people joining them in trucks from outside of Ramu. A college student who wishes to remain unnamed remembers the horror: “When the meetings were taking place, everyone joined in – AL, BNP, Jamaat-men. We thought that it would end with that – with them expressing their anger at their religious sentiments being hurt. People gave inflammatory speeches, for instance, the President of the Press Club, Nurul Islam Selim, said that if Uttam Barua is not handed over to them in two days, they will make everything dysfunctional. Other people said that the Baruas have disrespected Islam, now they must pay.” “The rest is history. At 11.30 pm, they brought a third procession towards Barua para, attacking people's houses. Then they went towards the temples. We told everyone – the SP, SI, the administration – no one did anything, not even the MP,” adds Shontosh Barua. A total of 12 temples were burnt, 6 more were wrecked and 50 houses were destroyed that night. The following day, the violence spread to Ukhiya, Teknaf and Patiya, destroying a total of 8 temples and monasteries, including two Hindu temples, and homes of Buddhists.

From newspaper reports, independent inquiries, police investigations and eye witness accounts, a few things have become obvious. One, that it was not a spontaneous act of communal hatred, but rather a pre-planned, meticulously orchestrated move on the part of the perpetrators. Not only did thousands of people come from all over Chittagong and elsewhere to join the attacks, clearly proving premeditation, but The Daily Star has recently unearthed that the said anti-Islam picture in Uttam Barua's profile page was actually photoshopped to make it seem as if the fabricated group, “Insult Allah” had shared the image with Uttam. There is no doubt, then, that vested groups had planned this attack in advance, using Uttam and a false story about insulting Islam as a rationale to incite other Muslims and to intimidate and devastate the Buddhists. The perpetrators knew exactly how to manipulate people's sentiments and turn Ramu, Teknaf and Ukhiya into sites of communal violence. What is less obvious, however, is who these perpetrators actually were, or what political motives they had. The locals argue that each group – AL, BNP and Jamaat – was involved, albeit in different degrees; it almost seems as if different groups led the attacks in the various areas in a rare act of camaraderie. But the question remains: if one group orchestrated these incidents, how or why did the other groups join in? So far 262 people have been arrested, including the two youth (one of whom has ties to Shibir) responsible for fabricating and disseminating the Facebook image, but it is as yet unclear who the real masterminds are. It is reported that extremist Rohingyas were involved in the events in some capacity. The locals, however, all agree on one front: the inactivity and inefficiency of the local administration in countering the riots. “The attacks continued for four hours. If they wanted to, they could easily stop or at least lessen the violence,” says Shontosh from Ramu. “They just stood back and watched, without even firing a blank bullet.” Nazibul Islam, the officer-in-charge of Ramu Police Station that night, was seen on the stage of a rally, making a provocative comment to the effect, “I am a Muslim. I should have also joined the procession.” He was immediately withdrawn from his post and an investigation is taking place to determine his role in the incidents. Inspector General of Police Hassan Mahmood Khandker further said that necessary actions would be taken if any police official is found guilty of neglecting his or her duty on that night. While the Awami League is blaming the local BNP lawmaker for “fanning communal violence,” in Ramu, the BNP is capitalising on the inaction of the local administration to point fingers at the ruling party. Irrespective of who is really to be blamed for orchestrating the incidents, the reasons for the failure of the local administration must be questioned and explored without delay, and [ir]responsible actors brought to justice. In particular, one needs to ask how violence could spread to Ukhiya Patiya and Teknaf the following day after the Home Minister herself assured that no more temples will be burnt. As a school teacher in Ukhiya says, “It is simply not an acceptable explanation to say that they did the best they could with the resources they had. We counted on them – the police, the MP, member and chairman – to protect us from the same kind of violence that happened in Ramu, yet they failed us.” But credit must be given where it's due. As a result of tremendous national and international pressure, the government has at least taken some positive steps to rehabilitate the victims, giving Tk 2 lakh, Tk 1 lakh, Tk 50,000 and Tk 40,000 per family considering the severity of property losses. The Prime Minister has also promised to rebuild all the temples and monasteries, but it is as yet unclear whether the government will manage to allocate a significant amount of budget to back up its promises. Even if no amount of money can bring back the priceless artifacts that were lost, a sincere commitment towards their restoration can go a long way to soothing the wounds of the Buddhist community. While the blame game and investigations continue, the residents of Ramu, Teknaf and Ukhiya struggle to go back to how things were before the attack. “Even if they could replace everything, the ancient statues and texts, the temples and monasteries, how would they address the insecurity and suspicion we feel now at every moment?” asks Nirmal Barua. Every Buddhist in the region registers surprise, confusion and hurt at the incidents that took place. “We have lived together for years, Buddhists and Muslims, as neighbours, as friends, as family almost. They would participate in our festivals and we in theirs. In the blink of an eye, all of that changed. Even if they didn't themselves partake in the violence, why did they not come forward to stop it? Why did no one say, 'This is our area, and these are our brothers. Turn around and go away?'”

Locals say that in Ramu it was mostly outsiders who carried out the atrocity. Although they recognise many of the Muslims who participated in the initial processions, they claim they don't know who conducted the actual torching and looting. “It was dark and we were too afraid to come out and face them, but it must have been outsiders,” say a Barua from Barua para whose house was torched. “It is impossible to think that someone we know can do this to us.” In some parts of Ukhiya and Teknaf, however, people claim that it was locals, people they recognised, who participated in the attacks along with unknown faces. “We have given the police a list of names of the people who we saw in the attack, and made them cancel the initial list they had created. We don't want innocent people to be framed or arrested,” says Mong Fu Barua, from Rajapalong Jadi Bouddho Bihar. Not everyone is as bold though and many choose to remain silent when asked to identify who the local leaders are in the face of threats or for fear of repercussions. There is suspicion and mistrust now where there was none a few weeks ago. How do you know anymore, they seem to say, whom to trust. Rajesh Barua (not his real name) shares, “No one apologised or expressed their sympathy to me after the incidents took place, except for one or two very close friends. My colleagues and neighbours pretended as if nothing had happened, and I got the feeling that they were talking behind my back. I almost feel as if they are happy that this happened. They (Muslims) have always been resentful of the fact that we Baruas are ahead economically and culturally.” Others, however, say that their Muslim acquaintances have condemned the attack, and given shelter and support when necessary.

The Muslims in Ramu who live near Barua para say they played no part in the incidents that took place. Except for a handful of brave Muslims who came to help their Buddhist brothers, most of them steered away from the violence for fear that something would happen to them. When asked if they participated in the meetings and rallies that took place before the torching, they say they heard of the commotion and some of the speeches, but didn't actively do anything. An invisible wall seems to have been drawn between the Muslims and the Buddhists since the attack. Even though there has never been any real tension between the two groups, the engineered incidents have succeeded in giving rise to a feeling of exclusion, insecurity and apprehension among the Baruas, making them feel like an 'Other'. The violence and its aftermath have also solidified for Muslims that the Baruas who live amongst them are actually different. As such, the events and the discourses surrounding them have done more than just destroyed Buddhist temples, artifacts and heritage; it has essentially created an artificial divide between people who have thus far co-existed peacefully. 'Divide and conquer' has long been a successful strategy of the ruling classes, and they have manipulated people's identities, constructing irreparable gulfs between different groups, to further their own interests. We need to figure out who benefits from creating these divides and in what ways. And although it is imperative that the perpetrators of the crimes be brought to justice immediately, and proper compensation accorded to the affected, it is equally crucial that we address the gulf before it cracks any further. Otherwise, the communal and anti-democratic forces would have succeeded.

A TIME ERASED Anika Hossain We live in a country that is known worldwide for most things negative. We are infamous for our high levels of corruption, political blunders and unliveable conditions. We have very few assets to be proud of such as the longest beach in the world and the largest single block of tidal halophytic mangrove forest - both of which are ill preserved and well on their way to ruin. It seems that the little that we do have in terms of cultural heritage and historical significance, which managed to survive ravages of time, are now under attack by our own people. The attacks on the temples, monasteries and homes of the Buddhist communities in Ramu, Ukhiya, Patiya and Teknaf have not only severed ties with and broken the trust of some of the most peaceful, harmless people in our country, it has also wiped out an entire period in our history.

The Buddhist community has not yet recovered from the shock of what happened on September 29 which is not only shameful, but should be considered a colossal loss for our country. Their homes and places of worship still lie in a heap of ashes, bits and pieces of precious artifacts lost under the rubble. An inventory is still being taken for what has been destroyed, but for now, all they can do is count on their memory to describe what they have lost. “Temples and statues made of chandan wood (sandalwood), each of them about 300 years old have been ruined,” says Kanak Chapa Chakma, renowned artist and prominent member of the Buddhist community. “Do you know, Chandan can no longer be found in Bangladesh and is rare in other parts of the world? Chandan has a unique, beautiful smell which is hard to forget. Religious manuscripts, which were 200 to 300 years old, have also been burned. We can spend millions of takas and re-build these temples and statues but the manuscripts will never be replaced. In fact, nothing will be the same. These were a part of our heritage, a part of our tradition and now they are lost. Our country has not seen this level of violence since the liberation war.” Kanak Chapa grew up in Rangamati, where Muslims, Hindus, Christians and Buddhists resided harmoniously in the same community. “When the Muslims celebrated Eid, or there was a Puja we never felt like this was something we were not a part of, it was our celebration too,” she remembers. “When we celebrated Buddha Purnima, they all came to our houses, wore new clothes and took part in our festivities. I never felt like they were separate from us, I never thought they were not Chakma or Buddhist so they had no right to be there. But after all these years, in these modern times, religion has yet again somehow come between us. When I first found out about what happened, I can't express in words how I felt. I cannot imagine people in our country being capable of such an act. When my children ask me why this happened, I am at loss as to what to say. There is no explanation that makes sense.” Artist and independent film maker Khalid Mahmood Mithu, who visited the sight of devastation, describes some of the artifacts that were destroyed in the attack. “There were some statues that were six to seven feet tall which were broken down. The statues made of metal, some of which date back 400 years while others are 250 to 300 years old, have been burned and melted down completely,” he shares. “One of the temples attacked was built about 450 years ago when Cox's Bazaar did not exist yet, but Ramu was on the British map. When businessmen from Myanmar used to come to Ramu, they would stay there for several days at a time, during which they met the Buddhist community settled there. They were grateful for the assistance and hospitality they received from this community and decided to build this temple for them as a gift. They brought large trees from Burma, with which they built each pillar of this two storied temple. This amazingly unique structure did not survive the attack on September 29, and the beautiful pillars were destroyed. There were also statues of two large lions at this temple, made of pure white stone, which the attackers tried to break and failing that, tried to burn but when they still remained unharmed, they pushed one of these off the second storey of the building. Ninety nine percent of all the statues that were attacked were beheaded, and the hands of the Buddha statues gesturing the abhay mudra were broken off,” he explains. “Their slogan was 'Naraye Takbir Allahu Akbar' and the beheaded Buddha statues are symbolic of that,” says Mahmood. According to Mahmood, among the scriptures burned, were the rare Taal Pata Puthi (religious scrolls on borassus flabellifer leaves). The entire collection of religious books belonging to the Ramu community was destroyed and their library burned down. “What I found interesting was that since Islam does not tolerate idol worship, attacking these statues could have been instigated by that, but the statues that were made of pure gold, were not destroyed, rather they were stolen which shows the mentality of the attackers,” says Mahmood. “My Mandir is 250 years old,” says Sreemat Sharamitra Thera, a Buddhist priest who lost his temple and home. “Many ancient, priceless artifacts have been destroyed along with the temple. About 50 to 60 Buddha statues have been broken and burned down, and our newly renovated roof has been destroyed. We also had a storage room which held 3 lakhs worth of temple property which has also been destroyed. We don't have anywhere to stay now and are living in tents.” A school teacher and member of the Buddhist community in Ramu, who wishes to remain anonymous due to fear of further assault recalls his experience the night of the attack. “I watched from the roof of my house as the temples were burned and homes were destroyed,” he says, fearfully. “I watched the flames for hours feeling completely helpless. The Borokang Buddha Bihar and Kendriyo Shima Bihar which were destroyed were about 400 years old. The Lal Ching temple was even older. You should have seen the artifacts that were destroyed. Artisans from Burma came to work on the stone altars where the Buddha Statues were placed, which were intricately and beautifully carved, many old scripture and scrolls were also destroyed,” he says. “Dhatu, which is what we believe are the remains of Gautam Buddha's nails or teeth were destroyed in one temple. Old religious books and doctrines were also destroyed at the Shima Bihar. My students have lost their homes and all our books have been destroyed. I am hoping they will be replaced soon,” he says despondently.

“Bangladesh may be a poor country, a very small country but we are culturally rich,” says Kanak Chapa. “We have hardly faced communalism before like India and Pakistan have. So why would a situation like this arise after so many years of living together peacefully?” The artist does not believe that what happened in Ramu and surrounding areas was a result of a single incident. She believes that it happened slowly and as a result of anger, envy, frustration and dissatisfaction. “I believe this is a result of political instability and tension,” she says. “We have been deprived of many things because of this political tension. Our leading parties, the Awami League and BNP, have no understanding between them, and are constantly blaming each other for all the problems this country is facing instead of working together to find solutions. I believe there were political forces behind this, and it is not a regular case of communal violence. Why else would people suddenly attack a completely harmless, peaceful community? I feel like as time goes by, people are becoming less tolerant of other faiths and losing trust in people, and after this incident the mistrust has turned into a deep-rooted fear,” she opines. “This was definitely a planned attack because most of the burnings were done using gun powder, which is different from a normal burning and leaves a whitish residue on the charred remains,” explains Khalid Mahmood. “I saw large drums/barrels that were brought in from other districts by trucks which contained petrol and kerosene. So this was definitely pre-meditated,” he says. “As a member of the Buddhist community, I feel that, when there is a peaceful demonstration in Dhaka, for example, held by professors at Dhaka University, who are not dangerous and are holding a silent demonstration demanding higher salaries, the police attack them viciously trying to break up the rally. But the violent attacks at Ramu and other places, started in the evening and went on till 2 am in the morning, and not one law enforcement officer, be it the police, RAB or even the fire brigade came to help the Buddhists. No one tried to stop it. I find that strange and suspicious.” According to Mahmood, the Buddhist community bears no anger towards their attackers. “I talked to many members of the community and what touched me was that not one of them said they want those who did this to be punished. They said they believe that these people have an anger and restless anxiety in their hearts and they hope that our creator and Gautam Buddha brings them peace and removes hatred from their minds. They are praying for their attackers.” The rift with the Buddhist community can only be rebuilt once we regain their trust. It is time we recover our long lost common sense and decency and show them we are ashamed of what has happened to them. Not only must we come together and help rehabilitate this community, we must voice our protest, so that appalling crimes such as these never happen again. |

||||||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |