| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 46| November 23, 2012 | |

|

|

Cover Story

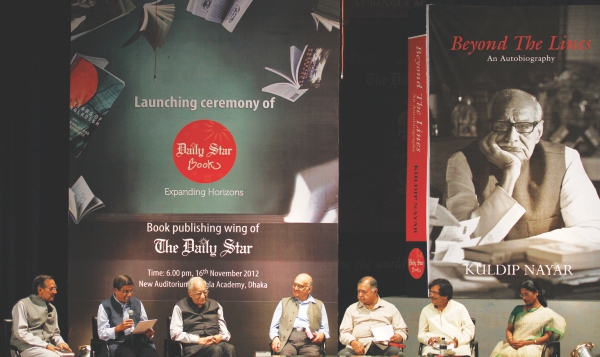

UNITING BARDS AND SCRIBES Sometimes the most extraordinary ideas take shape around a kitchen table. The Hay Festival is one such idea, founded by Hay Festival Director Peter Florence's father 25 years ago. The annual literary festival takes place in a small Welsh town of Hay-on-Wye and in recent years has spread to cities around the globe. The historic Bangla Academy in Dhaka hosted Bangladesh's second Hay Festival last weekend to great success and enthusiasm. The Daily Star was privileged to be the title sponsor of the event. More than 100 prominent Bangladeshi and 30 international writers engaged in exchanging opinions, stories and experiences with eager audiences. The three-day event showcased not only English literature from the west and other parts of the sub-continent, but provided Bangladeshis writing in English and Bangla a platform to present their work to the rest of the world. the Star highlights some of the exciting moments from the unique literary occasion.

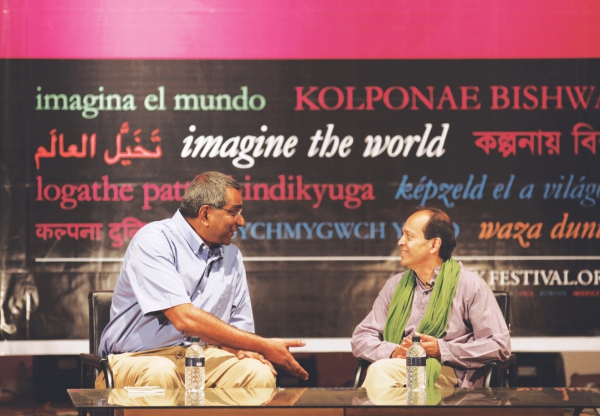

A SUITABLE AUTHOR ANIKA HOSSAIN The relationship between an author and his publisher is said to be based on a strong mutual trust. A publisher is the first person to read an author's work, which makes him perhaps one of the most important people in the author's life. Such is the bond shared by the celebrated novelist Vikram Seth and his close friend and publisher of many years, David Davidar also a writer. The conversation between these two charismatic men was the highlight of this year's Hay Festival. Not a seat in the auditorium or the balcony was left vacant, as the audience enjoyed the easy banter between the two men as they talked about each other's lives, careers and inspirations, entertaining them, with their wry, infectious humour. “David was a very brash young man,” says Seth, “You wouldn't believe it today, but when he approached the head of Penguin Peter Mayer (chairman of the multinational publishing company Penguin), he made quite an impression on him and was hired instantly. He basically started Penguin India. I would say publishing in the sub continent owes itself to this young man and his brashness. He had the huge ability to choose the people he could exploit, and the vast ability to show optimism where no optimism is due.” In the spirit of humour, Davidar shares his experience with Seth during the time his novel A Suitable Boy was in its editing stages. “We worked on that book together and we hated each other while we worked on it. Vikram moved into my house at the time because he didn't trust me to edit his book properly,” he says as he talks about how he had to explain the continuous presence of a “mad man” in his house to his wife. When Seth talks about his novel A Suitable Boy, he says “A Suitable Boy changed my life because I got overwhelming attention and it gave me enough money to be lazy for the next several years, which I think is very important. I am equally interested in poetry and it gave me the time to explore that. Every few years I collect my poems and bring out a volume, I very rarely do this because to me the important thing is to write the poems and once it's written it's done. This has to do mostly with laziness and the lack of organisation, where are these poems after all, I mean I've written them but where are they?”

Some of Seth's characters are drawn from real life, as his mother Leila Seth mentions in her memoir, the character of Haresh in a A Suitable Boy was inspired by her husband, Prem. Seth believes that his family does influence his work to a certain extent, “My relationship with my family provides, continuity and inspiration, the love and support in my life so therefore into my work but it is slightly double edged in that to some extent since you have to be true to what you are writing about, when you've are writing it, you can involve your family in so far as the characters and inspiration for characters in your books, but if it's the question of either trying to get their moral approval, or their moral acceptance of your work, then I think they can have a deadening effect on your writing because you will be censoring yourself, and you're not being true to yourself. So I will say, the closer you are to your family, the richer your writing is, but you have to be careful that this doesn't affect the verity in your writing.” When Davidar brings up the subject of politics in creative writing , Seth opines, “You can't inject your interest in land reform, human rights, communal tolerance, or in gender issues or anything and I'm talking about novels here, unless it has something to do with your character, unless they themselves are thinking about it.” When asked about how much he still cares about his previously published novels he says in all honesty, “The fact is I never read my books. I read them as a proof reader checking the spellings etc but I never read them through.” As the session comes to a close, Seth leaves the aspiring writers in the audience with a valuable piece of advice, he says “We have such a short life. I think you should write as well as you can, to the extent that you can, and I suppose if you are lucky, people will be reading your books, whether a decade or two or three afterwards.” The Stories of our War Tamanna Khan They come from three different countries and their experiences of the Liberation War of Bangladesh are diverse and incomparable. Yet this historical occurrence in 1971 seeps into their novels, defining the characters and plots and presenting readers with a book that holds something new, unique and unknown, perhaps. In the Tales of Liberation session of the Hay Festival, Bangladeshi writer Anisul Hoque, London and Karachi-based writer Kamila Shamsie and British author Philip Hensher discuss how the Liberation War of Bangladesh made its presence in their novels — Freedom's Mother, Kartography and Scenes from Early Life, respectively. For Anisul Hoque, writing about 1971 has been an obvious choice. He says that shouting slogans against West Pakistani rulers has been his first lessons at school as he was a class-I student during the war. Referring to the Liberation War of 1971 he says, “It taught us to become free, secular and more human. Every Bangladeshi writer gets inspiration from 1971. So it is not new that I wrote Ma.” 'Ma (Freedom's Mother)', which has been translated this year in English, is based on the true story of Safia Begum, mother of martyred freedom fighter Azad. Unlike Hoque, Hensher was far away from the war, yet the stories of the war would often visit him at family gatherings of his Bangladeshi-born husband Zaved Mahmood. Born in 1970, Zaved's childhood stories provided glimpses of the war, when narrated by his relatives. Hensher tells the audience how Zaved who appears in the novel as Saadi, a one-year old in 1971, was constantly fed sweet curd so that he would not cry. “I am not an auto-biographical author and I like to write about other people,” he says. When Hensher decided to write his extended Bangladeshi family's story he did not realise he would stumble into this huge historical event that affected every single Bengali in its own way. “I wanted to write an intimate story of the life of the family and how the war shifts their life,” he says, adding how the small things associated with the war came up in the novel rather than the huge political strife.

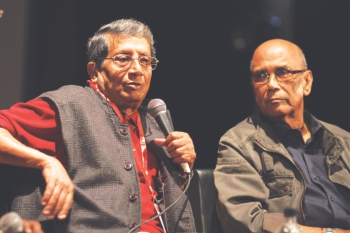

Kamila Shamsie on the other hand cannot keep politics at bay in her fictional works. Her characters set in Karachi face the constant violence that shakes the city everyday. “Your daily life is completely bound up with politics in Pakistan,” she says. Kamila opines that Pakistan has not learned its lessons from 1971. Born in 1973, she says she learned about 1971 from home. “During Ziaul Haq's years you didn't hear anything from the news,” she says. Later when she went to the US to study, she found that many of her Pakistani friends did not know about the atrocities carried out in Bangladesh by Pakistani Army in 1971. “I realised not every household told the stories.” Later when she comes back to Karachi in the mid-nineties and there's report of ethnic violence everyday, that she understands what had led to the Liberation War of Bangladesh. That is when she decides to write this novel Kartography, where the two young characters learn about their link to 1971 at a time when their world is rocked by Karachi's violence. Besides talking about their works, the writers discuss the editorial choices and responsibility while writing fiction, based on historical events and the research that needs to be done. Hensher believes, “A novelist has limitless freedom to write about real events. With this story I decided not to invent things to a large extent. Although the story of 1971 is familiar to Bangladeshis, the West has forgotten about it. So I felt it would be wrong to give English readers a wrong impression.” Hensher adds that he was influenced by Jahanara Imam's the days of '71 and like in the diary his novel too walks up to the violence of the war rather than being dominated by it. Referring to an incident which he made up in the 'Freedom's Mother', and which coincidently matched a real-life occurrence, Hoque says, “You have to make your readers believe this is happening.” Shamsie agrees by emphasising on the need for research and accuracy, “What you don't want the reader is to start doubting.” Butter Knives and Exploding Mangoes Soraya Auer "Writers being writers, cowardly and unpractical people, since they can't murder in real life, I think they tend to do it on the page,” Pakistani journalist and novelist Mohammed Hanif told a crowd of Hay Festival goers in the opening discussion of the three-day literary event. “It's very attractive that you can kill somebody and get away with it, which is what all murderers want but most don't achieve. But as a writer, you can.” Mohammed Hanif and Bangladeshi short story writer Anis Ahmed humoured the audience in a candid conversation with Sameer Rahim, Assistant Books Editor at The Daily Telegraph, UK, about conspiracies and assassinations in literature. The writers spoke about Hanif's 2008 comic novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes about Pakistani General Zia-ul-Haq's death by plane crash and Ahmed's short story Goodnight Mr Kissinger, published in a collection this month, about a Bengali waiter contemplating former US President Henry Kissinger's potential death by butter knife.

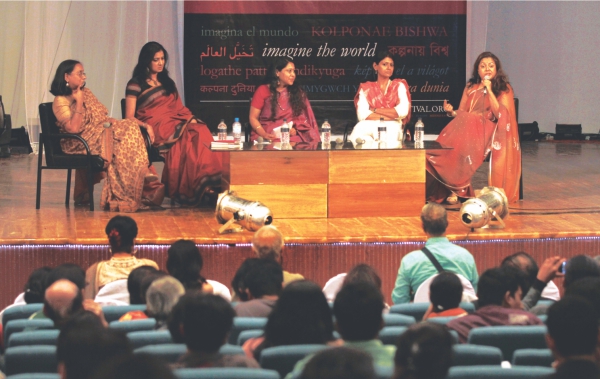

“The story is about a Bengali Christian waiter, whose father, a priest, was killed by the Pakistani Army during the war of '71, just outside Dhaka in Savar,” said Ahmed about his short story about a would-be assassin. “All these years later, he still can't forget that tragedy and harbours this grudge and anger.” That same anger resulted in the character beating up the son of a powerful man and being forced to flee the country for New York, where he finds work as a waiter. “One night, Henry Kissinger walks into his restaurant and given the whole history of his anger, how he lost his father and how he holds Kissinger responsible, the rest of the story revolves around why he shouldn't puncture Kissinger's throat with a butter knife,” summarised Ahmed, who was interested in exploring the issues of revenge and forgiveness and found violence very useful in structuring and pivoting his narrative. Having read and enjoyed the short story, Hanif chipped in, “As a reader I was kind of cheering on the guy. 'Come on, do it, pick up the knife, what's stopping you, what's taking you so long?!'” The novelist also brought the audience to laughter speaking about his own fictitious story, saying “Pakistanis are really brilliant at coming up with conspiracy theories. You tell them a basic fact of life and they won't believe it; they'll say somebody was behind it. Then you'll tell them the most fantastic thing and they would say, 'See, I told you. This is the truth.'” He shared, “Once a Pakistan retired general, who had been in intelligence [when the book is set], saw me at something like this [Hay Festival Dhaka] or conference. He put his hand around my shoulder and put me in a corner and said, 'Son, you've written a brilliant book, now tell me, who are your sources?' That was a bit scary.” The writers also put Sameer Rahim, the moderator for the panel, on the spot by asking him to clarify to him the details of the recent Petraeus scandal. Having read somewhere about an FBI agent sending topless pictures to someone, Hanif said “I can't figure it out so I thought because you work for a newspaper you might know what's going on.” Rahim quipped, “Don't believe everything you read in the newspapers.” VEILED EXPRESSIONS Anika Hossain Taboo is a word used to describe what society deems to be improper and unacceptable, and a word we as Bangladeshis are very familiar with, as a big part of life here is about censorship and skirting a variety of issues. Taboos are in a constant state of change, in the sense that over the centuries many have been and continue to be broken by people who choose to think outside the box and question the unquestionable. In the Hay Festival 2012, a group of such women, in film, theatre, writing (poetry and novels) and journalism talk about their struggle with taboos and how they have dealt with them. When moderator Firdous Azim raises the question about the topic they find most difficult to write about or represent in their work, each member of the panel brings to light the different forms of taboo they have encountered in their lives, some of which helps us rectify the common misperception that sex is the biggest taboo that exists in South Asia. “I think some areas are less about taboos and more about just being dodgy areas to talk about,” says Indian poet Arundhati Subramanium. “Such as cultural identities, I think we have definitive ideas for what it means to be Indian, and have to negotiate with that in our writing. I think that is one area that I had to deal with time and again. I also write about spirituality which isn't exactly a taboo, but far more difficult to talk about. I grew up in a circle where sexuality wasn't a taboo, what was far more difficult to talk about was spirituality because that was the new heresy in a way.” Author Audity Falguni shares a different experience with taboo. “I have been raised in a very traditional Bengali middle class family, and in this type of family, whether Hindu or Muslim, some traditions, like listening to Tagore songs, reading his work is still very much part of everyday life. We young women have read his carefully chosen words, never overtly sexual, talking about unrequited love, nothing about physical desire, everything is very platonic. So I have grown up learning to self censor, and censor my body.”

As a liberal minded actor, director and writer, Nandita Das has encountered social taboos on many levels, “I wrote Firaaq my first directorial debut and at that time, it was in a way a taboo,” she says as she talks about her film about the Gujarat carnage in 2002. “It is a taboo subject and being a democracy as India boasts of being, there is so much censorship at so many levels that you begin to think is this an illusion. I've been called anti national when I got an award for Firaaq in Pakistan, I got a lot of hate mail saying my passport should be confiscated, that I am a Pakistani, that I am an ISI agent etc, so basically there is a self censorship that is expected of you.” Das's career as an actor began with a controversial role she played in the film Fire, “For me, the subject I have seen in terms of taboo and I have grown personally with was actually a part of Fire,” She says “I liked the story and I thought even though I come from a very liberal family, we pretty much discussed everything and I questioned everything but homosexuality was a subject, that somehow we didn't talk about. And seldom does cinema have such an overt impact on society, one could actually see the impact of Fire whether in terms of legality, like we have a section 377 that criminalises homosexuality and that changed, Fire was attacked, theatres were burned down. People just spontaneously came out on the street and not only talked about homosexuality but questioned the arranged marriage system, talked about freedom of expression and a whole lot of things that it just drew out.” Writer Sharbari Zohra Ahmed has struggled with different identities and labels, which has had a great influence on her work. “I have two identities going on,” she says. “I am a Muslim and an American which is apparently an oxymoron. People have approached me and asked me to write about sex, in a very overt way because Muslim women apparently don't have orgasms, and I am supposed to illuminate that, and this is very difficult for me so instead what I did was, I stuck to what I knew. So when I wrote Raisins not Virgins I was thinking more about reconciling my Islamic identity with my American identity. And the taboo subjects that I hit on were the most taboo subjects in the United States, and one of them is America's unmitigated, completely biased support of Israel and the Israeli occupation in the Palestinian territory and I decided that was what I was going to hit head on. I knew I was touching on a subject that people would have an emotional reaction to, a visceral response, so I made it funny. That's why people trusted me and took the ride with me, because I made them laugh." As the session that expanded our knowledge and understanding of South Asian taboos drew to a close, Firdous Azim asked a final question, “Women have difficulty with exploring emotions, because as writers and performers, we are all so involved in being a certain kind of a woman, certain kind of a person that we forget other aspects. How do we break a cultural norm in which we have been brought up and which we value ourselves? How do we explore religion and spirituality and be this modern woman? To this, Subramanium replies, “I think the challenge is how to grow into yourself. That is a perennial journey. The challenge is how to bring this great messy creature that each one of us is, a mix of ideology and passion and body and how to condense all of that into a verbal utterance, that is true for you and hopefully, true for your reader. I think that is an endless process and that is always on.” A Call to Rise TAMANNA KHAN The one session, moving like a whirlwind and striking the audience's conscience for a change has been One Billion Rising (OBR) . Taking place on the wintry morning of the last day of the Hay Festival at the KK tea auditorium, the voices of the women discussants and performers, echo round the jam-packed hall. Human-rights activist Khushi Kabir, one of the organisers of OBR opens the floor, calling the audience to gather on the street on February 14, 2013 in protest against all kinds of violence against women. In her deep determined tone she translates the slogan of OBR in Bangla 'rukho, nacho, otho (strike, dance and rise)' She explains the number one billion, “According to UN statistics one in three women on the planet will be raped or beaten in her lifetime,” she says. Kabir adds that the gathering of one billion people on the streets across the world will show the collective strength and women's power in numbers, refusing to accept violence. “It will look like a revolution,” she expresses.

Performer and activist Nandita Das joins the call, saying that she still fails to 'understood how women become a minority' grouped in categories along with marginal groups such as ethnic groups. About the solidarity of OBR, she says, “The idea is to be more inclusive. Even in women's groups there are differences. Let us get over our differences in this platform. This is our chance to make it inclusive movement.” The programme continues with recitation of Sadaf Saaz Siddiqi's “The Sound of Silence” by Sushmita S Preetha, Taslima Nasreen's 'O Meye Shuno” by Nahid Sultana. Three volunteers read from real-life eve-teasing experience of women and girls, whose age ranges from seven to 69. Shamuna Mizan recites “My Short Skirt” – a reminder that what women wear is their choice and not an invitation for men to approach them. Munize Manzoor reads her short story based on a true incident where an indigenous girl was raped by policemen and when her mother tried to file a complaint at the police station, she was insulted by the Officer in charge. The programme ends with another strong performance “I AM OVER” — a pledge, an announcement that women are over all kind of discriminations and abuse and society's demeaning perception of them. February 14, 2013 marks the 15th anniversary of V-day which is a global activist movement to end violence against women and girls. The movement promotes creative events to raise awareness, money and revitalise the spirit of existing anti-violence organisations. Founded by playwright, performer activist Eve Ensler, the V in V-day stands for Victory, Valentine and Vagina.

DISCOVERING ZAFAR IQBAL Tamanna Khan Can you imagine the well-loved, white-haired science-fiction author Dr Mohammad Zafar Iqbal, in the role of Amit expressing his love for Labonnya through poems in Rabindranath Tagore's 'Shesher Kobita'? Probably not, but when Onik Khan, executive editor of Unmad, a Bangladeshi humour magazine, asks the author about his acting endeavours, he informs, “I had written a script based on the translation of Maxwell's Equation by a famous Russian author Anatoly Dneprov. I was the director of the play,” adding with a bashful smile, “I was the hero probably at 'Shesher Kobita' or a similar sophisticated play.” On the dusty green lawn of the Bangla Academy, Onik Khan draws out snippets of information about the popular author in front of a huge gathering of fans on the last day of the Hay Festival. The panel titled as Kotokhani Kolpona Kotokhani Biggyan actually ends up being an interview of Dr Iqbal, with the audience laughing and clapping as the author shares a joke or says something inspiring. The audience learns that their favourite author also used to host 'Kintu Keno (but why)'a science-education based programme in Bangladesh Televison in its early days. “We used to demonstrate scientific experiments there. Before recording we usually did a trial. I remember one experiment which showed that if a tree leaf is boiled in alcohol, the green chlorophyll vanishes. So I tried to test it and while pouring, the alcohol spilled on my hand and fire lighted up. The fire kindled like a torch and I kept on jumping not being able to stop it in any way. Finally the fire died down as the alcohol on top all burnt off. However, I was not hurt at all; only that my hand was on fire for sometime. I found it very amusing and thought about trying it again. But somehow it didn't happen,” Iqbal relates while Khan advises the audience not to try such experiments at home. Iqbal wonders why television channels in our country do not show any similar programmes on science education anymore. “To make an interesting science programme one need to do it with utter care, give a lot of time, be creative and spend a lot of money. Will a channel come forward to do so?” he asks. Referring to how difficult it is to get sponsors for math, physics or chess Olympiads, he says, “Those who sponsor they want to sponsor those programmes that are popular. You have seen the tirade of advertisements (in television). Thus if they show such frequent advertisements during a science programme who is going to watch that? He will surf off to other channels. I think those who sponsor need to think that 'I am sponsoring not because I want to sell my product but because the children of my country will get fun watching the programme, learn, love and study science and become creative'. If that happens, that people will sponsor not for money, not to sell product but for a social cause then I think good educational programmes can be made.” The conversation moves into the world of information and technology, when the audience discovers that Dr Iqbal had created the first Bangla font using his Macintosh computer. In fact, he says, he used that font to finish the only book that he ever typed and it was printed just as it was, without any editing. 'With all the Bengali spelling mistakes that I hoped would be edited, 'he adds, as the audience burst out laughing. Besides his science fiction, Iqbal is looked upon by young people of Bangladesh for always motivating them and giving them hope about the country. He talks about the one-forma book on the Liberation War of Bangladesh that he wrote, adding that from now on all his writings can be found in www.sadasidhe.com . Referring to an incident of illegal download of his books, he says he has decided to upload all his published books on the internet. Iqbal also discloses that soon readers will be getting a taste of his hand at poems. As a special treat for Hay-goers he recites two lines from one of his poems: Desher dakey sara dilam sobai bollo besh Learning from Drunkards Soraya Auer

"I have to start with a disclaimer: I am nothing more than a casual cricket fan,” declared Shehan Karunatilaka, winner of the 2012 Commonwealth Book Prize for his novel Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew, 'the cricket novel from Sri Lanka'. “I tend to rebel against that definition because it sounds about as appetising as a 'table tennis novel from Taiwan' or something.” The affable writer explained to Fakrul Alam and an audience, “What I set out to write was a detective story told by a drunk.” “I had such low expectations for this book that I didn't think it would be read outside of Colombo, so if I knew I would have rethought the title because it is a bit risqué and there aren't many Chinese people in the book,” says the Sri Lankan author. The novel follows an alcoholic sports journalist nearing the end of his life, who realises he's done little but drink arrack and watch Sri Lankan cricket. To give his life some meaning, he goes on a quest to track down a missing cricketer from the 1980s. “Once I stumbled upon the idea, I learnt a lot from that first book [which the author said “sucked”] so the first smart thing I did was quit my job and I dedicated two years to watching Sri Lankan cricket and hanging out with drunkards.” The freelance advertising copywriter and bass guitarist added, “You have to suffer for your art. You have to research.” In the name of said research, Karunatilaka recalled meeting interesting characters in local bars. “If you catch these old men, glued to the cricket match, between four and six, you'd find they were incredibly articulate and wise on numerous subjects from cricket to politics to the world. If you catch them after six, they're babbling and you'll probably just get in a fight with them.” Karunatilaka, who also won 2008 Gratiaen Prize and 2012 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, self-published his novel Chinaman until this year. He said, “There isn't a big publishing industry in Sri Lanka. It's quite cheap to self-publish, so it's relatively easy, going from typing, to printing, to on the shelves.” Writer and translator Alam gently chastised Karunatilaka for playing down his talent and the quality of his work. “Don't be misled by his summary of Chinaman, all about drunkards and so on, it is about so much else,” Alam told the audience. He assured them the novel was a pleasurable read with “diagrams, drawings and squiggles.” “The book ended up taking several turns I didn't think of. In the end, I think it really is about wasted genius,” said Karunatilaka, “and after subsequent drafts, I realised it was telling the story of Sri Lanka, which is a country blessed with so many resources but since independence, we seem to have squandered every opportunity and all of that so it's pretty heavy stuff for a drunk cricket novel but that's where it tended to go.”

BECOMING A WRITER Anika Hossain Many aspiring writers gathered at the Hay Festival this year to listen to their favourite writers talk about their work and what makes them successful writers and get useful tips from them on how to better hone their talents. In one panel dedicated to this discussion, chaired by Shazia Omar, a question was raised about the importance of balancing one's personal relationships and their career as a writer, to which author Lucy Hannah responds saying “When you need to write, you need to write, and you probably just need to manage the relationship section. You just need to be with someone who understands I think, and who gets it.” Novelist Philip Hensher adds “Or you need to get up early in the morning. I think a surprising number of writers do that. Toni Morisson, when her children were young, starting working around 5 o'clock in the morning. I am quite often at my desk by 7, and I have generally finished my day's work of writing fiction by half past nine or ten in the morning. And three hours of writing fiction a day is as much as anybody needs to do,” he says. When asked what it takes to become a successful writer, Hannah says “I think it has a lot to do with confidence, everybody tells stories, but whether you want to pursue a career where you want a wide readership is another thing and then 90 percent of the success is just turning up. So it's a bit before the 7 am that I worry about, which is getting to the sitting down, where you waste all the time.” To the question regarding how a writer keeps up his/her stamina throughout the process of writing a book, Hensher says, “Never finish a day's work at the end of a sentence and certainly not the end of a paragraph, and never ever ever at the end of a chapter, because the next morning when you get up what you face is chapter 23 and that's really hard. I would say it's about at page 100 that you run out of your initial ideas, my personal practice is to throw another couple of characters in the fire,” he says. “I always think a scene through and have an idea of what the next scene beyond that is going to be, but I like to have a few little islands of ideas of what's going to happen and I save them up for myself as treats.” According to Hensher, not all the characters in a novel have to be likeable. “I don't care if my readers love my characters... I think what your characters have to have is a sort of energy, attractive energy. They can be absolutely vile but you want to spend time with them. Whenever I read Emma by Jane Austen I think I'd much rather spend an evening with Mrs Elton than with boring old Emma or her boring old father eating gruel. So energy and the capacity to surprise, the reader, that's the thing to aim for, likeability..no no no no no no.” Writer Kaiser Haq, in response to this says, “The reader has to be interested in the characters, whether they are likeable or not,” leaving the audience with some important pieces of advice on how to become a disciplined writer as well as a successful one. Lost in Translation? On the occasion of the Hay Festival, Dhaka, the Star spoke to acclaimed authors about the challenges of translating Bangladeshi literature Zahir Hassan Nabil

A publisher in Dhaka phoned poet Mrittika Chakma to tell him that one of his poetry manuscripts in Chakma language, translated in Bangla, had been accepted for publishing. Mrittika would be given only 25 copies of the book, the publisher added. The poet requested another 20 copies that he would pay for and the publisher ensured those would be couriered to his address in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Mrittika waited, but not a single copy arrived, ever. Mrittika was feeling resentful about something he was not really sure of. In the discussion session Onno Shahitto – Writing from the Fringes at the Hay Festival at Bangla Academy, Mrittika talks about the lack of interest shown by publishers when it comes to publishing translations. He explains why it is important to translate literature to be reached out to the outer world because the literary realm reflects the culture of a people. “Litterateurs like Akhtaruzzaman Elias, Mamunur Rashid, Selina Hossain and Asadul Haque used to visit us and it was then that Elias repeatedly suggested writing our own novels. He stressed that we would fail in portraying our lives without the novels' narration,” says Mrittika, who believes the political turmoil in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) has also become a part of the culture of the indigenous people. It is certainly true, as Mrittika said quoting Elias, that a culture's literary artefacts, be it fiction or non-fiction, are absolute gateways for other people to delve into a distant culture. The artefacts are fashioned from within a culture, containing its essence, the way its people think, their emotions and glimpses into their lives.

“The publishers are not interested in us,” says Shuvashis Sinha, a theatre activist of Monipuri origin and a playwright in Bishnupriya Monipuri, a language very close to Bengali and Asamese. Some 16 years ago, Shuvashis had set up “Monipuri Theatre” with the vision of bringing Monipuri culture into animation on the stage, and to come together with the larger audience. “Though our culture originated from Monipur in India, we have grown up imbibing Tagore and Madhushudan and became intertwined with Bangladeshi culture. This land is ours as much as it belongs to the others,” he says. Saimon Zakaria, the talk's moderator, critically observes that the publishers are interested in the indigenous history, not literature. Saimon's observation puts in perspective the kind of postcolonial 'othering' persisting today. It seems the 'othering' that we, as the 'Indians', once experienced at the coloniser's ruthless clutch, was absorbed and harboured, only to be imposed upon the ones living in the 'fringe' today. As a matter of fact, Bangladeshi literature is somewhat similar to 'the literature from the fringe,' in respect to world literature. And in spite of the enriched literary tradition that Bangladesh rightfully boasts of, our literature encounters various hurdles put on way to reaching a vaster, global audience. Language remains as the first barrier, publishing and readership being the next. Why translation in English and for whom? Thanks to the information age for bridging distances– we have the internet, but it is not just about physical distances. Poet Gillian Clarke adds “In Welsh, English and Welsh languages coexist but are completely different; there is no other way than translating.” Translating and publishing more and more is seemingly the best solution to share literature. “When at school, I could read authors like Garcia Marquez because it was translated by then,” says writer Nasreen Jahan, in a talk on the Bangla Academy premises. “We have rich literary lineage from the 1960s, starting with Syed Waliullah, Akhteruzzaman Elias, Hasan Azizul Huq and Selina Hossain,” she adds. Nasreen's debut novel Urukku has been translated as The woman who flew by Kaiser Haq recently, one of the most known Bangladeshi writers in English. Nasreen said she waited for eight years for him to do the translation. On the other hand, Kaiser Haque, mentioning Urukku in the session Translating, says, “Professor Anisuzzaman gave me a copy and when I started reading it, I said why did I say yes? [to have it translated] It was a very difficult book to read.” Even the expert professes that translation is a formidable task. Dhaka University Professor Niaz Zaman, an editor of the Reading Circle of eight people who translated Kazi Nazrul Islam's epistolary novel Badhonhara, into Unfettered, said teamwork is useful while translating, “Eight of us jointly translated and it took about a year; we had a cultural editor and a copy editor as well.” Mahmud Rahman, who translated the Bangla novel Kalo Borof by Mahmudul Haq, into Black Ice, published by Harper Collins India believes translation requires repeated revision. “There was no way to translate the dialogues in Bikrampuri dialect in the novel," he says. "And there are certain words, for example, boti – there's no way of calling it a knife. I believe a translator needs to be able to write narrative prose in the language s/he is translating in. Getting a publisher who's an editor helps a great deal, I was fortunate to have Minakshi Thakur helping me for about two months with the final draft.” The matchmaking between the author and the translator is yet another hurdle to overcome as it happened in the case of Shaheen Akhter, who penned Talaash, the novel recently translated into English and published from India. “My Indian publisher chose a translator but I wanted a Bangladeshi translator, someone acquainted with the political situation in 1971 because the novel's setting was the Liberation War. The publisher disagreed and I could see many flaws in the first draft. The hassle was so prolonged that the translation actually came out in 2011 despite beginning eight years earlier,” says Akhter on the Bangla Academy auditorium premises.

The inherent features of words and literature are closely entwined with a nation's memory and history, which is a clear barrier for translating, explains Syed Shamsul Haque at the session Laureates. In response to Indian fiction writer Debesh Ray's comment that literatures of the two Bengals are not similar despite their proximity, Haque elucidates, “The Bengalis in West Bengal and in Bangladesh are different because of their experiences, so their literatures are different. The blood we have seen, the war we fought and the way we had defended our language is unknown to the others. Words have a resonance apart from its meaning, for example the word 'rokto' (blood) in Bangla literature would resonate and connote differently for someone who has seen the Liberation War. Language contains the memories and experiences of a nation, words are merely the outwardly manifestation. Even the numbers, remember 71? The number 21 means not bowing one's head.” For an author like Syed Shamsul Haque, ambidextrous in writing prose and poetry, translating is never 'perfect' as it never equates to the original. “It's impossible to translate poetry. At best, you can 'transcreate' a parallel version. I spent months over such bimbito kobita – reflected poems. Only the theme can be taken and reworked to create another poem,” opines Haque. But it's not just about translating. There has to be a readership for the translated body of work. There are people who know about Bangladesh, its heritage and literary lineage but why are we important? Why our literature? Why would they read translation of our works anyway? Author Anisul Hoque, whose book Ma has been translated in English from India, intervenes to answer such queries. “We claim that Bangla literature is enriched but the whole world is unaware because it has hardly been translated. There is no demand unless you are politically and economically relevant. When Japan started to do well and became relevant to America, then everyone paid attention to Japanese literature, the same happened in the case of India and China.” Anis exemplifies and suggests, “Jibonananda Das is one of the greatest poets but people would not read his works just because those are translated. We must get into the marketing process as well to brand ourselves that this is Bangladesh, the very kernel of literature for people really wishing to delve into the heart of literature.” In a talk after the session Lifelines, Selina Hossain stresses the importance of translating to convey our literature to the world. “What I gathered from this Hay Festival, after seeing an anthology of short stories authored by 15 women, and from my 25 years of experience in literature, some creative writers must write in English in tandem with translating other's works. I think some authors writing in English must commit to translating because poorly translated work in outdated English would never reach the larger audience. Only adept creative writers in English can preserve Bangla literature's flavour in translation.” Poet Nirmalendu Gun thinks despite a 'system loss' in translation, there is no alternative to communicate. “It's not about English, it's about a common language in which people belonging to different tongues can communicate and know each other's literature,” says the poet, laid back on a chair in the warmth of the twilight sun on the Bangla Academy lawn. As columnist Rubana Huq asks the panel of publishers in the session, Publishing Trends in South Asia, whether South Asia packages a lot of South Asian 'exoticness' of creative writing in the subcontinent. Publisher Diya Kar Hazra of Bloomsbury India says, “There are many reasons why South Asian literature appeals to the world today. I think we moved beyond selling exotica,” she says in satisfaction that there are different kinds of genres, and that the world is becoming smaller – thanks to the internet, thanks to people for travelling more, thanks to festivals like these, where lives and experiences are shared.

“There are wonderful biographies, short stories; it's not just exotic fiction that we used to read before. There are real stories, fiction like Anisul Hoque's Ma – that has been translated, there's incredible non-fiction, political work. We moved way beyond exotica; it's a wonderful time to be a publisher as well as a reader. I think this festival is an evidence of that,” she adds. Mahrukh Mohiuddin of the University Press Limited (UPL) admits that in the South Asian market, a lot of mass market titles, commercial fiction, romance and young adult, historical fiction, business books, books of prize winners and prize winning books are actually on the sale. “I think the publishers have a huge role and responsibility in creating trends and also determining the taste of the readers and creating a market,” she adds. In the larger context, things might just be different, when it comes to overcoming the hurdles of publishing and creating a readership for Bangladeshi authors' work. It is hard to determine whether the world would briskly become interested in reading our works but the publishers do have a great role to patronise translations and work as a catalyst to create the readership in the greater context. Translations of our enriched literary body of works must blend into this new and changing market-sphere and our publishers could certainly start with the works of writers writing in English. Sponsors and Partners: The Daily Star was title sponsor, Jatrik project partner, British Council global partner, with K&K Tea as key sponsor, AB Bank as associate sponsor, and Desh TV, Prothom Alo and ABC radio as media partners. |

||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |