| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 11 |Issue 51| December 28, 2012 | |

|

|

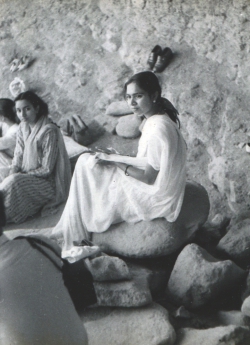

Remembrance Getting to Know you, Mother AASHA MEHREEN AMIN

As the sun sets each evening I am filled with an all too familiar dread that turns into a knot of pain and lodges itself somewhere around the throat and heart, refusing to get out, pinching at the flesh, threatening to make everything fall apart. This is the time when my mother Dr Razia Khan, writer, professor of English Literature and poet, was gasping for breath, when my father and brother were desperately trying to get her an ambulance, when I was agonisingly far away from her, trying to find some sort of transport – anything that would get me to her. But it was too late when I got there. As if in a dream I saw her lying in a cold little room on a trolley. I thought they were waiting for the doctors to do something. But then my father's ashen, deadpan face said it all. He refused to break down even as I felt some strange animal sound coming out of me. I was crooning 'Ammu' - an epitaph I had used when I was a little child and had somehow abandoned for the more formal 'Amma' along the years of invisible distancing. I try to block out that image as much as possible but it keeps slithering into my consciousness as soon as the sun sets as if a replay of that terrifying day will go on over and over again. It was today, December 28th that the world turned upside down for us. In the blur of the sea of people who came to our house in the following few days, to stand beside us and comfort us, I almost forgot what had really happened. It didn't hit me until I decided to clear the fridge as food kept coming in as is the custom during bereavements and we needed space to keep it. It was finally my opportunity to break down freely as nobody was around - there it was, that plastic container of dried cranberries. It was what she had been holding when I had visited her in the morning of that day. I had been surprised to find her sitting in the verandah (usually being confined in bed most of the time) trying to get as much sun as the wired netting would allow. She looked regal with her mane of white hair, though her face was pale and it seemed as if she was looking through me. I grabbed a few cranberries from the container - she murmured something like 'do you want a spoon' obviously not approving of the fact that I had taken a few of her favourite snack with my hands. The next moment my brother came along and did the exact same thing and produced same response: “Isn't there a spoon somewhere?” She was obviously alert enough to notice our bad habits but there was something off about the way her eyes just stared onwards without really focusing on anything. I asked her if her nose was blocked and she said: "Maybe". It was probably the first indication that she was having problems breathing but I was too obtuse to understand. The duty doctor had declared the cause of death: lack of oxygen to the brain.

Later when lunch was served in her room she said, "Today the three of you should eat downstairs in the dining room". It was bizarre for her to say that as we always had food with her in her room as she couldn't walk down the stairs anymore. Was she trying to set precedence? In the days that followed we would continue to sit downstairs as there would no longer be any reason to have meals in my parents' bedroom. She kept telling me to go and not be late for my Wednesday meeting and something kept telling me that I should stay. I lingered a few seconds more as I leaned down to kiss her goodbye and left, brushing aside my gut feeling and replacing it with mundane pragmatism that I would regret for the rest of my life. What is really unfathomable is that time doesn't always heal, not when you have just started to get to know someone after they have passed on. My relationship with my mother was always a little strained. We were opposites in every way. I always felt I was never good enough, that she thought I was mediocre compared to her brilliance which was quite obvious. I always had to take opposing sides as our perceptions were often diametrically opposed to each other. But I know I craved for her love as did my brother, as she was not very expressive about it. Her spontaneous bouts of affection seemed to have ended as soon as we left our childhood. She was possibly quite wary of the strangeness of our adolescence that brought with it inexplicable rebelliousness. Often she would be annoyed at my ignorance, at my average intelligence– I wasn't reading Karl Marx at 14 as she had nor had I written a novel at 19. She found a stash of Mills and Boons and a few Harrold Robbins hidden far behind a desk drawer and was totally disgusted, treating them like dirty magazines. She had expected better. The only thing she could think of was to hand me a copy of 'Golpo Guchcha' thinking that would miraculously cure me of my crass reading tastes. Perhaps it did a little as in those lonely hours when it would be just my mother and I in the house (my father was posted abroad and my brother studying in the US) I would wander into the living room and discover her treasure. They were random books - 'Potrait of an Artist' which made no sense at all to me at that age, 'Anna Karenina' which became my first love and loads of George Elliot (who was her latest favourite) and Henry James. Thankfully my brain, for the time being, was at least diverted from inanity and depravity.

It did not take long for us to realise, though much too late, that she was rather extraordinary as a person. Despite being fiery, independent-minded, unconventional and a formidable presence in any literary circle, she was also very attached to the idea of family. She was strict about the usual things – having breakfast no matter what especially the compulsory oatmeal porridge- taking baths before our lunch – things from the 'must do' list of all mothers. But unlike most of them she would get annoyed if we studied at our desks for too long, saying it was so boring, that we should get out and play. Being a member of the National Censor Board, she would often take us to see films, sometimes getting horrified at some unforeseen adult content as we tried to keep a poker face throughout those scenes. She was a music lover and often put on cassettes of Rabindra Sangeet which she would sometimes hum to herself as well as records of Bach and Chopin. She had dreams of my brother, Kaiser, who was musically-inclined, of being a concerto pianist. Later however, my parents gave him an acoustic guitar, I am sure after a lot of pleading on his part. The instrument became his life-long companion, turning him into a gifted musician, although he chose banking as a profession. Many years later my mother said she had agreed because she thought it would be a good way to keep away from drugs which many teenagers had become addicted to. My brother claims it was to keep him from chasing girls. I couldn't help but marvel at her foresight! I don't think I really comprehended the complex, brilliant person who we were living with. Not when she went on innumerable literary conferences, not when she won awards for her writing, not when she had published several books, not when she gave unbelievably articulate and inspiring speeches at events we were often 'required' to attend, not when men and women of all ages would come to her and behave like crazed fans as they were her former students. It was because she was so blasé about her accomplishments, sometimes even a little secretive. Perhaps she did not think we would appreciate her enough and therefore pre-emptively distanced herself. It was not easy to know my mother. Most people didn't get her subtle innuendos and sarcasm. But over the years we – the three of us – began to detect the danger signs of extreme irritation or anger. Sadly she misunderstood many people who loved her dearly and pushed them away from her life, leaving her all the more isolated. At the same time we did have many laughs together and those are the moments that I would like to remember. Our passion for afternoon tea was one of those rare things that created a bond between mother and daughter. She would often regale us with childhood anecdotes that gave an indication of just how much she missed those carefree days. Her politician father's frequent sojourns meant my mother grew up travelling all over the sub-continent - Kolkata, Karachi, Dhaka, Faridpur. It makes her one of the rare breed of individuals who have experienced the history of the subcontinent, being citizens of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. When my daughter was born, she became a source of great joy for her. Finally she seemed to have found someone to express her unconditional love. I was amazed at her tolerance towards my child, who as an infant, was extremely boisterous and demanding. But her grandmother seemed to have been turned to putty in those little hands, allowing the little imp to do whatever she wanted. Yet it was her husband who was her best friend and it was only after she had gone from our lives that we realised how he loved her with total devotion. She was not very effusive in her affections but he was her anchor, her security and strength there was no doubt. The most amazing thing about her was that she evoked so much admiration, love and respect from so many people which was evident during her funeral and commemorative programme on her birthday February 16. To most of them, even those who had reached great prominence in society, she was affectionately called 'Raju' as did her side of the family and close friends. Despite her trying so hard to isolate herself especially when she became practically homebound, there was no dearth of grief and shock when she left this world. Most of the time I feel as if she is there somewhere and that at some point I will call her and she will complain about my father tiring himself out with over-activity. But if I happen to be alone at sunset, that overpowering feeling of loss creeps back in. It is a pain I don't want to go away no matter how debilitating. It is an ache that reminds me of who my mother was and what she means to me.

|

||||||||||||

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2012 |