Midwinter Merriment

By Risana Nahreen Malik

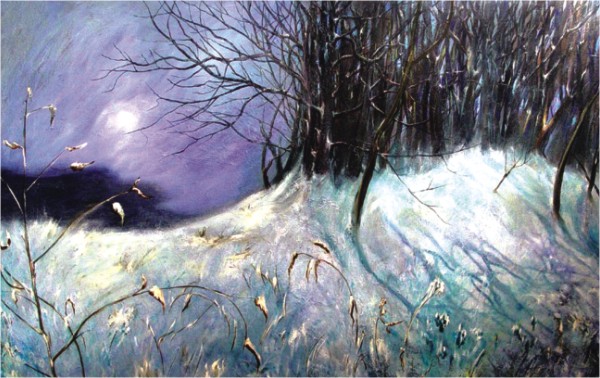

Shivering under sweaters and reflectively shovelling down ice cream, it's easy to wax romantic about winter solstice. On the longest night of the year, the wait for the dawn feels interminable, doubt encapsulated by the dark. The darkest hour comes, light dies a little death, right before the glow and the rays slinking in through the window. The world feels relieved, hopeful; things can only get better now, and you can feel spring hiding under leaf litter, snow and morning mists.

It's nothing new, though; merely another shared sentiment in the historical-geographical tangle of existence. The symbols of death and the promise of rebirth have fascinated people since the seasons set in and rest assured that they didn't have to wait till 0 A.D. to find cause to celebrate winter.

To begin on somewhat familiar ground we have Yule, which you might associate with your favourite winter holiday. Yule, however, dates much further back as a pagan celebration for cultures throughout Northern Europe. It's hard to pinpoint its origins because the celebrations diverged with the civilisations and Yule now refers to a medley of similar Celtic, Nordic and Germanic festivals. Essentially, though, as with midwinter in most cultures, it was meant to observe the end of the darkness; heralding sunlight and longer days, the beginning of another spring. In Scandinavia, Yule was a religious as well as cultural occasion as feasts were arranged and sacrifices made to honour the gods or 'Yule-figures.' Christmas celebrations absorbed many of these traditions as the religion took over so you can still find traces of ancient rituals in the elaborate dinners, the holly and mistletoe, the burning of Yule logs and singing carols.

The ancient Greeks observed winter solstice as the death and resurrection of the god of grape harvesting and wine, Dionysus. Lenaia was a predominantly female rite, where women sacrificed a young man to enact the god's death at the hands of his female followers, the intoxicated Maenads. His birth was symbolised by a newborn child presented in the performance (just the baby, not the… rest). Fortunately, goats replaced the human sacrifice once that sort of thing went out of fashion and the women's roles in this 'Festival of the Wild Women' were reduced to that of bystanders. The Roman festival of Brumalia, the Shortest Day, was based on this. The Romans, however, left out most of the gory bits and probably just engaged in drunken revelry.

The ancient Greeks observed winter solstice as the death and resurrection of the god of grape harvesting and wine, Dionysus. Lenaia was a predominantly female rite, where women sacrificed a young man to enact the god's death at the hands of his female followers, the intoxicated Maenads. His birth was symbolised by a newborn child presented in the performance (just the baby, not the… rest). Fortunately, goats replaced the human sacrifice once that sort of thing went out of fashion and the women's roles in this 'Festival of the Wild Women' were reduced to that of bystanders. The Roman festival of Brumalia, the Shortest Day, was based on this. The Romans, however, left out most of the gory bits and probably just engaged in drunken revelry.

You had quite a few divine beings hankering after midwinter birth-and-death anniversaries, actually. Osiris, the son of Ra, was one. The Babylonians followed suit, their winter solstice festival, Zagmuk, commemorating the triumph of the sun god Marduk, over darkness. Shab'e Chelleh, the birthday of the Persian god of soldiers, Mithra, shared that purpose and is still observed by numerous ethnic groups in Iran, as a time for family gatherings and (again) feasts reminiscent of the ones that were held to ensure the protection of the winter harvests.

The fact that winter solstice marked the ascent of so many Sun deities did, like Yule, eventually influence Christianity to a great extent. When the Roman emperor Aurelius unified the perceptions of the sun god as Deus Sol Invictus or the 'Unconquered Sun' he forged bridges between the different religious groups within the empire, a single idea that they could relate to when a monotheistic religion took over. The Festival of the Birth Unconquered Sun, Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, was eventually established as December 25th, and, in time, memories of Mithras, Osiris, Helios and Sol gave way to the name we now know so well.

The element of the rebirth of the sun existed in winter solstice observances beyond the Roman Empire too. The Inca god Inti was heralded back on Inti Raymi by a ceremonial 'tying' of the sun to stone pillars in places of worship. Being in the Southern Hemisphere, though, this was observed in June. Native American tribes had similar rituals to bring back the sun. Soyalangwul, observed by the Hopi Indians, involved making 'prayer sticks' to entreat the sun to awaken and bless the community. And in seventh century Japan, the sun goddess Amateras was persuaded to return from her cave by the other gods, invoked through prayers and feasts. We really like our feasts, don't we?

Most of these festivals no longer exist; they've been phased out with the civilisations and we don't usually celebrate the solstices or equinoxes for themselves anymore.

Most of these festivals no longer exist; they've been phased out with the civilisations and we don't usually celebrate the solstices or equinoxes for themselves anymore.

However, there are a handful of cultures that still feel the spiritual significance of the turning point of the seasons. The Dong Zhi festival in China is still one of the most important, considered to be, in a sense, the beginning of a new year. As days become longer after the solstice the East Asians recognise it as the influx of positive energy restoring the yin-yang balance.

Makar Sankranti celebrates the movement of the sun into Capricorn and its ascent in the sky after winter solstice. It has numerous names throughout India Poush Sankranti and Magh Bihu from West Bengal and Assam might sound more familiar and, like Dong Zhi, it commemorates the longer days differently within the country, from kite-flying to bathing in the Ganga, making offerings to the sun god. This holiday, however, is scheduled according to the zodiac, which imperceptibly shifts over the years in relation to the solar calendar so, while it used to be celebrated in December, the beginning of the Uttaryana, the sun's northward movement, it is now held in mid January.

Midwinter as a celebration of life: it's a lovely thought, nestled between the season's usual associations with darkness, death and endings. The shortest day, the smallest span of sunlight, the point from which things can only get better; a thought as old as life itself. This Christmas may be a brilliant opportunity to binge on cookies and marzipan (though why people would want to binge on marzipan, I'll never know) but why not remember the solstice, for a change? And, ancient or no, it's never stopped our feasting.