The Revolution Rising

There are changes happening. Of that, there is no doubt. After years of apathy to the state's indiscretions, the people have finally risen up and made themselves heard. But what exactly have we risen for? We have two viewpoints that reflect the combined voice of the Bangladeshi youth and what a professor of Political Science at Dhaka University thinks about the whole affair; one down below, the other on Page 8.

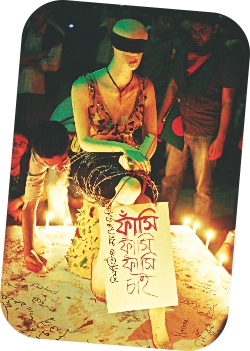

Photo Credit: Mohammad Ar-Rafi Waseq Hossain

Photo Credit: Mohammad Ar-Rafi Waseq Hossain

BY SHAER REAZ

It has almost been a week, and the movement at Projonmo Chottor is still going strong, the moshals and candles still burning bright. One question seems to be on everyone's lips. Have you been to Shahbag?

It is hard to describe it to someone who hasn't been there (yet). The crowd is electrifying; the entire place gives you a chill down your spine and raises the hair on your arms. Whether you're against capital punishment and consider the throngs of people at Shahbag, chanting for Rajakar blood, to be misguided in their bloodlust, or if you support the movement wholeheartedly, there is no denying the fact that this is BIG. The Y2K generation and those barely old enough to remember the Twin Towers coming down are going to Shahbag, making it the first time this generation has taken to the streets for their country's cause. When a political party threatens civil war on a country in an attempt to stop the trial of war criminals, all the while harboring dreams of a repressive state run by fundamentalists, it's natural that the younger generations would want to do something to prevent it. Shahbag represents two generations of ideas: one part witnessed the atrocities committed during 1971, and are there for the justice of those who betrayed our fight for freedom; another is there to ensure these “janowars” in the shape of men never have a say in our country's politics ever again. At Shahbag, there are protesters chanting for a death sentence to Kader Mollah on one side, while others shout for the blood of any who supports or sympathizes with Jamaat-e-Islami.

“Justice delayed is justice denied”. What sort of message is it sending to the future generations if we say that consequences for crimes of murder have a time limit? The process of trying the war criminals has started 40 or so years late, but it is never too late to serve justice to those who have committed unspeakable crimes. From the Nazis to war criminals from Bosnia and Chechnya, all have received their fair share of punishment, so do we not feel shame, as a nation, that we still haven't seen justice done for the atrocities committed against our people? We caught up with Dr. Shantanu Majumder, professor of Political Science, University of Dhaka for his views on Shahbag.

“The Shahbag movement, in my eyes, is a start down the path of countering the fundamentalist politics that has festered in Bangladesh, and its also a movement for a more open political landscape. It might not be a very progressive movement, but it is the first time that the neutral individuals in society (those not associated with any political party) have organised themselves to reject the greatest hurdle in Bangladesh's development as a nation: fundamentalism.

One of the main indicators of the fact that this is an apolitical movement is that the crowd's slogans have Joy Bangla, and not Joy Bangabandhu, thus separating themselves from any political party. And they are saying it with conviction, even the people who have never shouted Joy Bangla in their lives.”

RS asked him, “Do you not feel that this movement is misguided, or fruitless? Will they actually achieve what they are occupying Shahbag for?"

He replies, “It is usual for any big movement by the masses to not take into account the details and minor loopholes, as we should focus on the main point here: why is the younger generation coming onto the streets? They are taking a stand against the fundamentalist politics that they believe are detrimental to the development of the nation, and that is something that I admire and support. Shahbag is an explosion of the pent up anger of the general masses at the mistreatment of the public by the antics of all the political powers of the country. The Shahbag movement is the general public's way of flexing its muscles and showing everyone that the power lies not with any political party, but with the people.”

So do you personally support the death penalty?

“I teach Human Rights courses on a global perspective, and three out of 4 lectures are spent on anti-death penalty arguments. When I go to Shahbag, even though I'm not giving slogans, I am sure that I am not contradicting myself, because I believe that the people there are rising up with the same spirit of 1971, no matter how vague that notion may be. I personally think that is very important and admirable in the youth of today.”

Even if you are against capital punishment and oppose any sort of bloodthirsty politics that Bangalis by nature are associated with, you should give the whole matter a thought and see if you agree with the view that this just might be the start of a major change in the way Bangladeshi politics are conducted. Power to the people, anyone?

The Devil's In The Details

By Ibrahim

Shahbagh has been transformed into a figurative battlefield complete with the hue and cry of people from all walks of life demanding 'justice' for the atrocities committed by the war criminals. The protests started when ICT-2 gave a life-term to Kader Mollah, someone the general public believes deserves the death penalty. Away from the united backlash the government is facing, this issue does bring up several sticky points for all of us to ponder.

Firstly, the growing despondency shows a lack of faith towards the judiciary. The same judiciary and indeed, the same tribunal which was applauded a few days back for providing the death sentence to Abul Kalam Azad. The fact that we have raised a complaint now would mean that the entire judiciary system is inept. A protest on that is absolutely fair in its own right. Only protesting against one verdict might not be the wisest thing.

Firstly, the growing despondency shows a lack of faith towards the judiciary. The same judiciary and indeed, the same tribunal which was applauded a few days back for providing the death sentence to Abul Kalam Azad. The fact that we have raised a complaint now would mean that the entire judiciary system is inept. A protest on that is absolutely fair in its own right. Only protesting against one verdict might not be the wisest thing.

Secondly, away from all the sentiment, there is still confusion as to how this demand can be met, if it ever will. The prosecution has already won on all the cases, save one and only that can be appealed which, according to the ICT Law of 1973, cannot be used for a death penalty, either. There are talks of an amendment to the laws but that, too, has far reaching consequences. The premier of the country has come out urging the judges to take heed of the people's expectations as well as following the law before delivering a verdict and this is a contentious issue as the legal system is best kept independent. According to Mohaimin, a student, “Without structural changes, it creates a dangerous precedent where the state veers quite close to a fascist state, away from democracy.”

Another talking point among the youth is the apparent evolution of this movement. From demanding death for the war criminals there is now a palpable sense that the public want religion-based to be abolished. They are now clamouring for Jamaat and Shibir politics to be brought to a halt. This was the inevitable step, according to some people we interviewed. “It's been a long time that we've sat idly by and saw horror stories every day on the news and strikes crippling the economy thrown by Jamaat and it's time we took a stand to stop it once and for all,” says Sharif, a regular at Shahbagh for the last few days. However, any movement needs to have a strong coherent voice to it if it is to succeed at all. Think back to Tahrir Square and how voices of the protesters fizzled out into nothingness as the Islamic brotherhood took advantage of the situation. That's why the recent six-point charter was a crucial point in the movement. Without a unified voice, the manipulation of politics can creep in and the youth have been loath to do that so far, admirably enough.

And on to the matter of the demands themselves, the demand for death penalty rears its head. And it is evident from the reception by the global media, usually suckers for any kind of revolution, that this is something the wider world does not condone in the 21st century. This writer himself is against capital punishment in principal and it is unnerving, to say the least, to see toddlers screaming out 'faashi chai'. The oath also contains demands for abolishing religion-based politics, which, going by the general consensus, is something that has been left to fester for way too long. And here, again, the demand for death does them no favours as 'eye for an eye' isn't the best way to tackle fundamentalism. It needs to start from the ground up and requires a complete overhaul of education and ideas about religion and politics so that's one battle we will have to keep on fighting. But the cause for consternation came when the charter contained a demand to boycott businesses with ties, sometimes allegedly, to Jamaat. This will, and I quote, 'cripple the economy' as many civilians with no ties to any war crimes will suffer and lose jobs. And the consequences will be just as bad as any Jamaat or Shibir strike. It's up to the general public to decide if they want to throw their weight behind this and it cries out for more thorough research away from any infectious sentiments of Shahbagh.

And on to the matter of the demands themselves, the demand for death penalty rears its head. And it is evident from the reception by the global media, usually suckers for any kind of revolution, that this is something the wider world does not condone in the 21st century. This writer himself is against capital punishment in principal and it is unnerving, to say the least, to see toddlers screaming out 'faashi chai'. The oath also contains demands for abolishing religion-based politics, which, going by the general consensus, is something that has been left to fester for way too long. And here, again, the demand for death does them no favours as 'eye for an eye' isn't the best way to tackle fundamentalism. It needs to start from the ground up and requires a complete overhaul of education and ideas about religion and politics so that's one battle we will have to keep on fighting. But the cause for consternation came when the charter contained a demand to boycott businesses with ties, sometimes allegedly, to Jamaat. This will, and I quote, 'cripple the economy' as many civilians with no ties to any war crimes will suffer and lose jobs. And the consequences will be just as bad as any Jamaat or Shibir strike. It's up to the general public to decide if they want to throw their weight behind this and it cries out for more thorough research away from any infectious sentiments of Shahbagh.

The emotions run high in Projonmo Chottor and it is refreshing to see Bangladeshis stand up and demand justice for once, compelling even. And what happens in the coming days will decide the legacy of the Shahbagh movement. Will it be seen as another false start which promised so much and inspired so many? Or will we be able to move away from the basal desire for revenge and make an indubitable change in our country, where our voices no longer choke in the face of discrepancies by the government? Time to make it count.